The programme Energy+ was a co-operative market procurement initiative between various European countries running from 1999 to 2004. The purchasing power of large buyers was combined in order to give manufacturers of household appliances an incentive to produce highly energy-efficient appliances. The overall goal was to transform the appliance market sustainably. The product group focussed on refrigerators and freezers. They had to be at least 25% more energy-efficient than appliances of the same size and function that just met the EU energy label’s A-rating requirements. The number of Energy+ manufacturers and models meeting the Energy+ criteria gradually progressed. While in 1999, there had been only two models available, this increased to 866 models produced by 21 manufacturers that inscribed their products in Energy+ lists in 2004. If Energy+ cooling devices have 100% market penetration in the EU-15 by 2020, annual energy savings are estimated to be close to 40 TWh. The chances are good, as from July 2014, an energy efficiency level close to Energy+ requirements will be the minimum energy performance standard (MEPS) in the EU for refrigerators and freezers.

Energy+ was the first programme promoting co-operative market procurement between various countries. The idea was to find influential purchasers and to define energy efficiency requirements and other environmental characteristics for refrigerators and freezers. The overall aim was to use an aggregated purchasing power to transform the market. Energy+ buyers were either housing companies, with more than one million dwellings altogether, or retailers, with more than 15,000 shops across the Energy+ partner countries. Supporters such as consumer advice organisations informed private households of the benefits of Energy+ appliances to further stimulate demand.

By showing to the manufacturers that several strong purchasers are interested in energy-efficient products and that there is a potential market for these efficient products, the manufacturers were willing to make these appliances available on a larger scale (Labanca 2006). The significant demand for energy efficient appliances minimised the financial risks for manufacturers by advancing into hitherto rather uncertain market segments.

In the first project phase (1999 – 2002), ten European countries participated in Energy+. In this initial period the project decided to focus on two-door refrigerator-freezers and single-door refrigerators with a four-star freezer compartment. Both refrigerator-freezer combinations had to be at least 25% more energy efficient than appliances of the same size and function that just met the EU energy label’s A-rating requirements.

Later, during the second phase (2002 – 2004), other types of refrigerators, freezers and their combinations were integrated into the programme and three more European countries joined.

Energy+ comprised various sub-measures. A logo signalled that products fulfilled Energy+ criteria (see the figure above) The Energy+ Award accelerated the development of appliances even more energy-efficient than demanded by the Energy+ minimum performance criteria and drew media attention to the programme Energy+ lists highlighted manufacturers and purchasers committed to the selling and buying process, and the website gave information to potential and already active participants.

The number of Energy+ manufacturers and models meeting the Energy+ criteria gradually progressed. While in 1999, there had been only two models available this increased to 866 models produced by 21 manufacturers that inscribed their products in Energy+ lists in 2004.

Overall the project was funded with €1.7 million of which about one third was given by the European Commission. An evaluation of the impact has been difficult due to manufacturers’ reluctance to publish their sales data. However, market analysis shows that in 1998 the market penetration for A and B classified 4-star refrigerators and two-door refrigerator-freezer combinations, the most energy-efficient at that time, was 58% and 54%, respectively. This figure increased by 20 percent (4-star refrigerators) and 22 percent (refrigerator-freezer combinations) in 2000 (Thomas et al. 2003, 39).

Other policies also contributed to the successful market transformation of household appliances across Europe. Country- and city-specific measures facilitated the success of the programme. For example, in the Netherlands and in the city of Aachen (Germany) grants were given to customers buying highly energy efficient appliances. It was the Dutch energy rebate scheme “EnergiePremieRegeling” that was especially instrumental in accelerating the introduction of more energy-efficient refrigerators and freezers with the new classes A+ and A++ not only to the Dutch market, but to the whole European Union. The criteria for this programme were informed by Energy+: A+ and A++ appliances met Energy+ criteria, with A++ saving another 30 % of energy compared to A+ or Energy+ minimum requirements. Read more in the bigEE good practice policy example on the EnergiePremieRegeling.

In 1991, under the Swedish Technology Procurement Program (STPP) the Swedish National Board for Industrial and Technical Development (known as NUTEK) established a procurement programme for energy-efficient computer monitors, lighting, washing machines, windows, heat pumps for single-family houses, industrial flow control systems, and refrigerators/freezers. For each appliance category, NUTEK identified strong (demand-side) actors and published purchasing proposals. With regard to refrigerators/freezers, the purchasers intended to take 500 highly efficient appliances for rental properties. “Highly efficient” was defined as 40% more efficient models available on the market. According to NUTEK, with total costs of over 311,000 USD (adjusted to 1990 USD-levels) for the refrigerator programme, it was considered to be cost-effective and helped to increase purchases of energy-efficient refrigerators/freezers from 0.02% in 1991 to 5% in 1994 (International Institute for Energy Conservation 1995).

Between 2006 and 2008, the Wuppertal Institute, the Austrian Energy Agency, the Centre for Renewable Energy Sources and several others implemented a follow-up programme of Energy+ for highly efficient circulating pumps in 27 EU member states, called Energy+ Pumps. While institutional purchasers declared to buy an efficient pump, regional and local energy agencies, NGOs and others agreed to support the initiative, among other things, by distributing information material (dena NA).

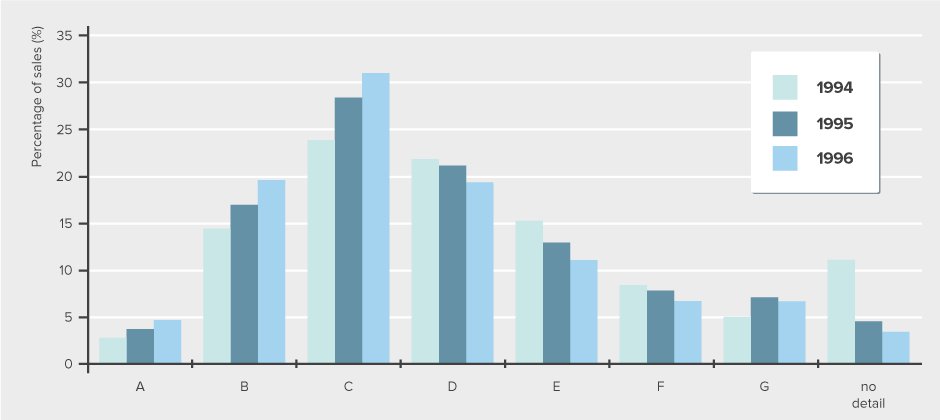

In 1998 6% of Europe’s final electricity consumption was estimated to be due to refrigerators and freezers (Labanca 2006, 4). Market penetration for the most energy-efficient two-door refrigerator-freezer combinations and 4-star refrigerators at that time, rated A or B, was low, although the market share grew constantly between 1995 (31% and 18%) and 1998 (54% and 58%). Against the backdrop of the Kyoto Protocol concluded in 1997, European c-ooperation to reduce CO2 emissions in general and electricity usage of refrigerators in particular was a reasonable step.

In Germany, the average energy consumption for two-door refrigerator-freezer combinations was 307 KWh (A-rated) and 416 KWh (B-rated) on average.

The core goal of the programme was to increase the market penetration of highly energy efficient cold appliances by approaching both demand and supply—i.e. large purchasers and appliance manufacturers.

The measure was also used as a field test for the instrument of bulk purchasing (also called co-operative market procurement) on the European level.

Another aim was the preparation of manufacturers for tightening the EU’s Energy label and minimum energy performance standards. Voluntary arrangements such as Energy+ gave manufacturers time for adapting their product range (Thomas et al. 2003, 31).

While coordination is located at the supra-national level, each of the ten participating countries has an individual agency to coherently implement and supervise the measure within the country-specific context.

The programme targeted the development, production, sale, and purchase of highly energy-efficient refrigerators. It did so by using an aggregated purchasing power in order to ultimately transform the market and to increase the energy efficiency of cold appliances overall.

In the first phase until early 2002, criteria for both sub-categories (two-door refrigerator-freezer combinations and 4-star refrigerators) were as follows:Although the policy initially approached bulk purchasers to invite them to purchase Energy+ appliances and create a demand pull, the actual goal was to offer an incentive through the increased demand and thus to pull appliance manufacturers to the production and marketing of energy-efficient refrigerators and freezers. So basically, manufacturers which were also involved in the stakeholder process were the main focus group. Energy efficiency increases in refrigerators and freezers can be achieved through improvements of the cooling cycle or through component improvements. While some components were produced by refrigerator-/freezer manufacturers themselves, others were fabricated by external suppliers making them a supplementary target group as well (Thomas et al. 2003, 34f.). However, the project would not have worked without the commitment of the bulk purchasers, i.e. housing companies and other landlords, and appliance retailers. Furthermore, since most cold appliances are sold to individual households in the residential sector, supporters such as consumer organisations and energy agencies informing these end consumers were also an important target group.

The EU energy label was quite significant for Energy+ because the minimum requirements for an A-grade constituted the baseline of Energy+, and the standard test procedure for energy efficiency that was defined for the EU energy label was also used to define the Energy+ requirements. On the other hand, “[E]nergy+ assumed the role of facilitator and catalyst helping identify efficient cold products in the period immediately preceding the revision of the energy label thresholds” (Labanca 2006, 7).

Apart from that there were several measures interacting with Energy+ in participating countries. For instance, in the Netherlands energy efficient product purchases (A-rated) were promoted through a financial incentive. Activities of the Dutch Energy+ team resulted in even higher subsidies for appliances meeting Energy+ criteria (2001: €90, 2002: €100). In this way, the Dutch energy rebate scheme “EnergiePremieRegeling” was instrumental in accelerating the introduction of more energy-efficient refrigerators and freezers with the new classes A+ and A++ not only to the Dutch market, but to the whole European Union. A+ and A++ appliances met Energy+ criteria, with A++ saving another 30 % of energy compared to A+ or Energy+ minimum requirements. Read more in the bigEE good practice policy example on the EnergiePremieRegeling.

The fact that in Germany the municipal energy company of Aachen provided financial incentives of €50 for Energy+ appliances shows the very decentralised support for the programme.

The measure includes innovative features.

Energy+ was the first pilot programme to test the instrument of bulk purchasing (also called co-operative market procurement) at a multinational scale. The measure was introduced to find evidence to show whether or not bulk purchasing at that scale could lead to a sustainable market transformation in the whole EU (Thomas et al 2003, 4).

The interplay between the European and the individual national level was regarded as a great success. “On the one hand, the European character of Energy+ stimulated the interest of cold appliances manufacturers in the initiative as they address the whole European market, and the regulation they have to comply with in relation to energy performance of their products is developed at European level. On the other hand aggregation of demand side, stimulation of its interest towards energy efficient cold appliances and verification of the presence of these appliances in the various European countries could only be achieved by acting at national level” (Labanca 2006, 3).

The measure included an Energy+ Logo and an Energy+ Award competition, both raising the profile of the programme. More importantly, the logo signalled to buyers, products fulfilling the criteria set by Energy+. The Energy+ Award Competition encouraged manufacturers to develop and produce even more energy-efficient appliances. The winner of the 2004 Energy+ award in the category two-door refrigerators and freezers even met the criteria for the A+++ class that was only introduced to the EU Energy label in 2010.

Current activities and developments are published in a news bulletin submitted to participating stakeholders (manufacturers, bulk purchasers, national Energy+ teams) twice a year. More information, directed towards current and potential future stakeholders is available on the web (Thomas et al. 2003 47ff.). The 50 or so Energy+ supporters were also very important for increasing awareness of the programme.

Possible further improvements could have been possible. The measure focused on the most efficient appliances available on the market, but it could have also aimed at influencing technical product characteristics. This would have led to even more energy-efficient products (Thomas et al. 2003, 2).

Unfortunately, funds for testing product conformity were only possible in the first Energy+ phase. “In 2000, 5-6 Energy+ models were bought by the collaboration and tested by the test institute TNO in the Netherlands” (Labanca 2006, 24). In order to improve monitoring the conformity, the measure could have integrated spot tests from time to time.

The policy package could have been optimised too.

An early and concerted action of financial incentives in many EU member states could have further accelerated the market breakthrough for Energy+/A+ and A++ appliances.

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement Energy+

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

As the policy was located at the supranational level, co-ordination functions lay with two organisations during the first phase and during the second phase, while implementation rested in general within national energy agencies. This was necessary for country specific market peculiarities and contacts to bulk purchasers, supporters and national branches of manufacturers.

Funding

The European Commission (EC) funded the programme to about one third. Some additional funding was generated through national budgets.

For the first phase of the Energy+ project, the overall funding was €1,000,000, of which 35% was provided by the European Commission. The second phase cost €753,250 of which 31.39% was given by the EC (Labanca 2006, 9). Funding for testing product conformity was only possible in the first Energy+ phase.

Test procedures

The EU energy label has own test procedures for energy efficiency that were also used by the project to define Energy+ appliances. Therefore no specific own test standards were needed.

In the initial phase, a feasibility study was initiated. It focused on three questions:

First phase, Stage 2 (1999/2000 – 2002)

In the first implementation stage, lists of bulk purchasers and of qualified appliances were published, so-called Energy+ Lists. Moreover:

Second phase, Stage 3 (2002-2004)

Energy+ was then expanded to all the products / subgroups of the two main categories. A second Energy+ Award competition for manufacturers, bulk purchasers, and supporters was launched.

Quantified target

The proposal for the first phase (1999-2002) mentioned a target to shift 1 % of the market (62,000 units) from the then average class C to Energy+. It estimated annual energy savings of 250 kWh per unit or 15.5 GWh overall.

For the second phase (2002-2004), the proposal estimated a 5 % market share and annual savings of 200 kWh per unit or 62 GWh overall.

International co-operations

The Energy+ project was inherently an international co-operation.

In the first phase of the project (1999-2002), 10 European countries participated in Energy+ (Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden and the UK). In the second phase (2002-2004), three other countries joined the programme (Belgium, Greece and Switzerland).

Actors responsible for design

During 1997 to 1998, Statens Energimyndigheten (STEM), the Swedish Energy Agency gathered a team of energy agencies and scientific institutes to analyse the feasibility of multinational co-operative procurement projects, building on the Swedish experience. This study and the development of the preliminary design of the Energy+ project, which was later refined during the first phase of the project, received funding from the European Commission. The measure itself was then initiated under the umbrella of the Specific Actions for Vigorous Energy Efficiency (SAVE) programme of the European Commission.

Actors responsible for implementation

A number of national energy agencies took responsibility for the overall co-ordination:

In the first phase of the project (1999-2002), Statens Energimyndigheten (STEM), the Swedish Energy Agency, and

Agence de l'Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l'Energie (ADEME) from France shared this task.

Both, ADEME and STEM, hired the consultancy International Conseil Energie (ICE).

In the second phase (2002-2004), SenterNovem from the Netherlands took over the co-ordination, again working with ICE.

For the second phase of the project launched in 2002, the following national Energy+ teams joined:

Monitoring

There was no comprehensive monitoring system in place keeping track of the sales or purchasing data. However, for later evaluation purposes various kinds of documents were analysed. Though understandable, it was and remains a difficulty in that stakeholders have been reluctant to publish their sales or purchasing data.

Evaluation

An evaluation does exist: Thomas et al. (2003): pp. 32 – 54 and Labanca (2006)

However, the Energy+ programme was carried out together with other initiatives aiming at a similar target (market transformation). Moreover, some countries such as the Netherlands provided financial incentives for the purchase of Energy+ qualifying refrigerators or freezers. Thus, evaluation results differ from country to country and attribution of savings to Energy+ is practically impossible.

Design for sustainability aspects

In the Energy+ Award competitions, CFC- and HCFC-free refrigerants and foaming agents were required and a low global warming potential was rewarded.

The following barriers have been experienced during the implementation of the policy

Implementation barriers differed depending on the country context. For example, in Germany, unlike in Nordic Countries, finding bulk final purchasers was not an easy task.. German homes are almost never let with appliances included. Moreover, for other potential bulk purchasers such as halls of residence, the criteria for the devices did not fit their demands; the net volume of 200 to 300 litres was oversized. The ultimate buyers in Germany were households. As this group is far too decentralised appliance retailers were identified as the only possible bulk purchasers in Germany.

The following measures have been undertaken to overcome the barriers

In the countries, in which homes are not let with appliances included, the project co-operated with appliance retailers as bulk purchasers. Furthermore, Energy+ engaged with supporting organisations such as energy agencies, consumer organisations and energy companies, who provided independent information on the benefits of Energy+ appliances to the private householders who were the ultimate buyers of the appliances.

The target year was 2002 for the short-term impact and 2020 for the long-term impact.

For the short-term impact of the project, “Potential savings were estimated under the hypothesis of a minimum direct effect of shifting 1% of the 1996 European market (i.e. 62 000 units) from an average European model (a C-rated one consuming 500 kWh per year) to a highly efficient class A model, which would have used no more than half of this C model's consumption, i.e. 250 kWh per year. Under this hypothesis the gain would have been a saving of 15.5 million kWh for one year” (Labanca 2006, 10).

If Energy+ cooling devices have penetrated the EU-15 market by 100% by 2020, there will by energy savings of about 40 TWh annually compared to BAU.

Taking together all the European countries, savings would even add up to 60 TWh per year. These figures are only rough estimations.

Expected additional, yearly energy savings in kWh/year

Labanca (2006) mentions expected annual energy savings of 250 kWh/year on average per Energy+ appliance.

An evaluation was done for the final project year 2004.

Concrete figures in energy savings/year

Attribution of market development and energy savings to Energy+ is extremely difficult as manufacturers, retailers, and purchasers were also influenced by the revision of the EU energy label (with the new classes A+ and A++) and financial incentive programmes.

“According to a very rough estimation published in the final report of energy+ project (ref. 6) about 0.5 millions of energy+ appliances were sold in 2004 determining 100 GWh (0.36 PJ) of [annual, comment by the authors] energy savings. Using Eurostast (1990) figures 0.36 PJ of saved energy corresponds to about 45870 tons of CO2 emissions avoided” (Labanca 2006, 28).

The core goal of Energy+ was to increase the market share of highly efficient appliances. Data was scarce at that point of evaluation. However, market analysis shows that in 1998 (before the policy) the market penetration of A and B classified 4-star refrigerators and two-door refrigerator-freezer combinations was 58% and 54%, respectively. This figure increased by 20 percentage points (4-star refrigerators) and 22 percentage points (refrigerator-freezer combinations) in 2000 (Thomas et al. 2003, 39).

Due to the facilitating role of Energy+, the number of models meeting Energy+ standards increased from 2 in March 1999 to 866 in March 2004 (Labanca 2006, 23).

In the final report for the second Energy+ project phase, Electrolux France pointed to the fact that A+ and A++ models made 7.8% in their global refrigerator sales and 5.2% in freezer sales in 2004. Figures of A+ and A++ models making around 7% of the respective market share were confirmed for the whole market by the CEDEC. It was regarded as a “continuously growing market” (SenterNovem NA, 41f.).

The chances are good that by 2020 the market will have been transformed to only selling refrigerators and freezers meeting Energy+ requirements, as these will become the minimum energy performance standard in the EU from 2014.

Achieved additional, yearly energy savings in kWh/year

The above estimate of savings in the order of 100GWh/yr from 0.5 million Energy+ refrigerators and freezers is equivalent to an energy saving of 200 kWh/yr per unit.

(Net) Cost savings vary significantly depending on country context (e.g. due to differing electricity prices) and the manufacturers’ pricing strategy. Henceforth, it will not be possible to make generalised statements.

As the average life cycle of a refrigerator or freezer is said to be around 15 years, the measure is likely to be beneficial to the final consumers even at price increments of 10% to 25% for Energy+ appliances (Labanca 2006).

Comparing the estimated cost of the Energy+ programme of 1.2 Euro-Cent/kWh (see actual costs above) with EU electricity wholesale market prices of 4 to 6 Euro-Cent/kWh, the programme was clearly cost-effective. This is also very likely for most consumers who purchased Energy+ appliances. Their energy costs saved are much higher—between 10 and 25 Euro-Cent/kWh, yielding annual savings of 20 to 50 Euros if an Energy+ refrigerator or freezers saved on average 200 kWh/year, as has been estimated (Labanca 2006). This is likely to be much higher during the estimated 15 years of lifetime compared to an estimated incremental purchase cost of 10 to 25 %, which might be a range between 50 and 250 Euros. In addition, the Dutch rebate scheme drove down the incremental cost of energy-efficient refrigerators and freezers (read more in the bigEE model example of good practice on the Dutch EnergiePremieRegeling).

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy