The Top Runner programme, developed and introduced in 1998 by the Japanese government, is an innovative approach to increase the energy efficiency in the appliance sector as it identifies the most efficient appliance of a product category and defines this product as the minimum performance standard, which has to be reached within a specified number of years. 23 product groups are covered by the programme estimated to account for 60% of household electricity consumption in Japan. Due to the Top Runner programme, Japan was able, by 2009, to improve the energy efficiency of the selected product groups by 19% (27.1 TWh) and all in the period from the base year to the target year, on the assumption that products met their target values.

The Top Runner programme is a regulatory scheme, which was initiated by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in 1998. It is designed to stimulate continuous technological improvements by the manufacturers of products towards an increased use-phase energy efficiency of selected product groups.

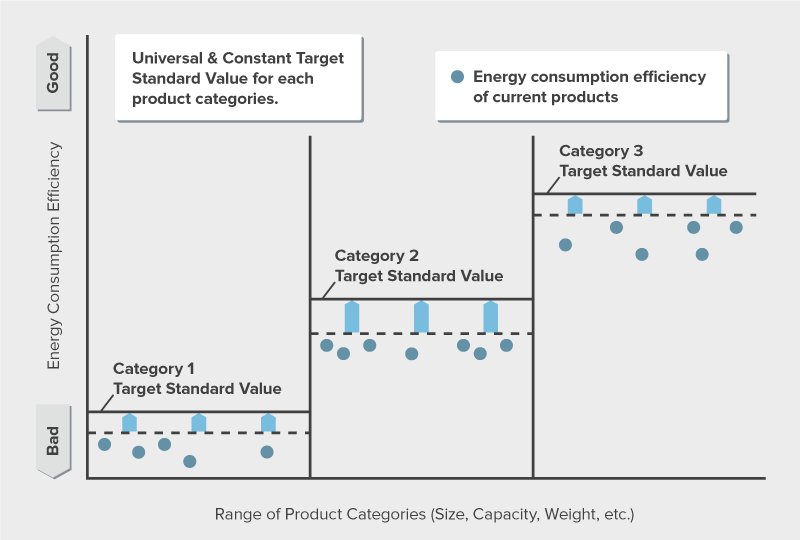

The underlying logic behind the Top Runner approach is to identify the most efficient technologies in the market and define their efficiency level as the top runner standard (100%) from which target values are derived. By the target fiscal year, manufacturers have to meet these standards for the (sales weighted) average of their products (METI 2010). Therefore in comparison to MEPS, the Top Runner programme – in principle - does not ban products from the market. Inefficient products can be produced and sold if they are compensated for by the sales of high efficiency appliances (Siderius & Nakagami 2012). The setting of target values takes into account potentials for technological innovation and the diffusion of products in order to keep incentives for the development of more efficient technologies on a constantly high level. The next figure illustrates a very simplified structure of the Top Runner standards setting process. Target years are set for each product group and range between 3 to 11 years with an average of 5.6 years depending on the specification of the respective product group. Within this timeframe, manufactures have to make sure they meet at least the defined standards. These standards are reviewed when the target year arrives or when a certain proportion of suppliers have already met the defined standards.

Overall revisions of the Top Runner took place in 2002, 2005, and 2009 involving evaluations of process and standards, as well as extension of the programme to new product groups. Today, the Top Runner programme covers 23 product groups in the residential, commercial and transportation sector.

The standards set by the Top Runner programme are used for a couple of other policy instruments in Japan such as the Green Purchasing Law, an eco-point action scheme, and the e-Mark programme, a voluntary and a mandatory energy labelling scheme, which informs purchasers about the percentage achievements with regard to the defined Top Runner standard of an individual product. Read more in the bigEE file on the policy package for energy-efficient appliances in Japan.

Results, in terms of energy efficiency improvements arising from the Top Runner programme for 13 out of 23 Product groups, can be found in the most recent publication of METI (METI 2010a). Initial energy efficiency improvements for 13 technologies were expected to reach 35 per cent in the period from the base year to the target year (5-10 years). The effective achievements for the same period and products amounted to 48 per cent and thereby outplayed estimations indicated by the Top Runner Programme (METI 2010, p. 9). Another evaluation by Siderius & Nakagami (2012) calculated energy savings for 10 product groups. The results are listed in the following table. These results are a conservative estimate and consider savings for the situation where all products in the stock had been replaced by more efficient products in accordance with the standard (in the period from the base year to the target year).

| Top Runner Product | Consumption 2009 | Energy Savings | |

| TWh/year | TWh/year | % | |

| Refrigerator-freezer | 40.1 | 8.4 | 21 |

| Lighting equipment | 32.8 | 1.8 | 5 |

| TV sets | 21.8 | 8.1 | 37 |

| Air conditioners | 18.1 | 4.1 | 23 |

| Electric toilet seats | 7.6 | 0.7 | 9 |

| Personal computers | 6.1 | 2.6 | 43 |

| Rice cookers | 5.6 | 0.6 | 11 |

| Microwave ovens | 4.4 | 0.4 | 9 |

| Routers | 2.7 | 0.2 | 7 |

| DVD recorders | 2.2 | 0.2 | 9 |

| Total | 141.4 | 27.1 | 19 |

Source: Siderius & Nakagami 2012, p. 7

The Top Runner products account for almost 60% of household electricity consumption (244.6 TWh in 2009). The savings amount to 19% of the consumption of the Top Runner products and 11% of total household electricity consumption.

In the case of non-compliance, the Top Runner programme takes a “name and shame” approach. First METI makes a recommendation to the non-complying producer to improve products and then goes public if the producer does not comply. Thus far, the name-and-shame approach appears to be working well in Japan: no manufacturer has been publicised as being non-compliant to date (UNESCAP 2012).

Japan is the only country having the Top Runner approach implemented. Therefore no other examples can be mentioned here.

Japan’s final energy consumption has continuously risen due to its economic development. In the 2000 fiscal year, Japan’s energy consumption was about 9 times larger than in 1955 (METI 2010, p3). This is very relevant because Japan has almost no domestic energy resources of its own and relies on energy imports. The turmoil caused by the first and second oil crisis in the 1970s convinced Japan’s decision makers to perform a policy shift towards energy supply source diversification.

In 1979, Japan enacted the “Law concerning the Rational Use of Energy” (Energy Conservation Law), which provided the legal basis to push on with energy conservation activities. While the final energy consumption of the industrial sector decreased due to efforts by the companies, the consumption by the residential, commercial and transportation sectors kept on rising except in the time during the oil crisis. This trend was mainly caused by the public’s pursuit of richer lifestyles following economic growth (METI 2010, p.5).

The Energy Conservation Law set energy efficiency standards for machinery and equipment, but these were limited to only three items (electric refrigerators, air conditioners, passenger vehicles). The standards were set so as to stimulate manufacturers and importers to achieve the standards through the company’s voluntary efforts. In 1999, following Japan’s commitments related to greenhouse gas reduction made at Kyoto, the Energy Conservation Law was revised in order to strengthen energy conservation measures. The Top Runner programme and other policies were introduced to tackle the challenge of reducing final energy consumption by advancing energy efficiency. After the earthquake in 2011 and the resulting accident at Fukushima nuclear power plants, the role of energy efficiency became even more relevant.

The Top Runner programme is designed to stimulate continuous technological improvements by the manufacturers of products towards an increased use-phase energy efficiency of selected product groups. It supports the diffusion of energy efficiency innovations.

It is a national policy.

The Top Runner programme was introduced to tackle the challenge of reducing final energy consumption by advancing energy efficiency for machinery and equipment used in the residential, commercial and transportation sector.

Due to the limitations of bigEE the residential sector (and partly the commercial and public sector) is considered in this section.

The Top Runner mainly targets the design phase of energy-using products in order to reduce energy consumption during the use phase of a product.

The programme defines mandatory energy efficiency standards for all product groups in focus. Standards are mainly based on the most energy-efficient product (Top Runner) in the respective product group. The most efficient products set the standard for all products to meet in the next target year.

Additionally, standards setting takes into account expected potentials of technological innovation, diffusion, and the product price. This means that very expensive products will not be used to set the standard. The standards are also not set by patented technologies (Siderius & Nakagami 2012, p. 2).

Once defined, standards become legally binding from a defined target year and manufacturers have to make sure that their products meet them in corporate average. The fixed requirements of the Top Runner programme differ depending on product specific characteristics across and within product groups. The standard can also be set above the value of the best product (as was done for DVD players) (Siderius & Nakagami 2012, p. 3).

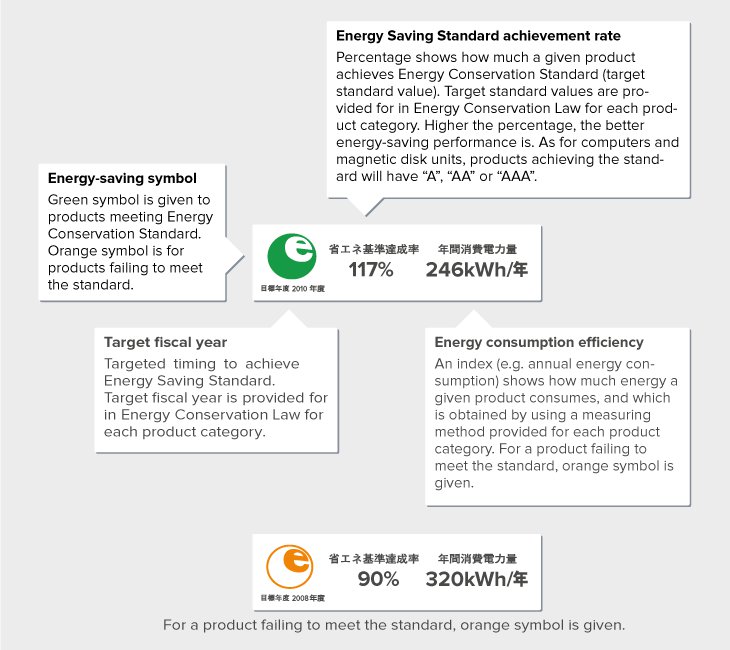

Besides targeting the actions of manufacturers, an additional mechanism in the framework of the Top Runner programme is concerned with the purchasing decisions of end users. A supplemental labelling scheme, the so called voluntary e-Mark scheme, enables end-users to draw informed purchasing decisions by showing how far a certain product has achieved the energy consumption efficiency standard of the Top Runner programme (see the next figure).

The Top Runner programme is an integrative part of the Energy Conservation Law. There are several areas of intersection with other policies. For instance, the e-Mark programme is a voluntary labelling scheme, which informs purchasers about the percentage achievements with regard to the defined Top Runner standard of an individual product. Another example is the Green Procurement Law, which incorporates targets defined by the Top Runner programme into purchasing decisions by public institutions (Nordqvist 2006, p.13-15). Another policy interacting with the Top Runner programme is Tokyo’s energy rating label. This local energy label adopted by Tokyo’s municipal administration uses Top Runner related criteria in its design (see the figure below).

Furthermore, Japan introduced an annual energy-efficiency award scheme and the e-Shop commendation scheme. The latter targets household appliance retailers of a certain size and invite them to compete for prizes and the privilege to name themselves an e-Shop. The scheme awards only such shops which are specialised on energy efficient devices and which can provide outstanding service concerning their distribution (Berghammer 2010, p57).

Since 2008, the eco-action points system awards consumers for energy-saving measures. Consumers receive eco-action points when they purchase energy-saving appliances or take energy-saving actions. The eco-action points can be exchanged for energy-saving goods or other actions (e.g. private railways, restaurants and other stores) at participating shops and thereby further promote environmental awareness (Nordqvist 2006, p. 14). For more information about the Japanese policy package and the interaction of single policies and measures go to our detailed description.

Whereas MEPS are often comparable to other product standards from other countries, the Japanese Top Runner has some unique features (Siderius & Nakagami 2011, p. 2). Therefore, the programme includes some innovative elements

The Top Runner programme is innovative in the sense that it uses the highest current energy efficiency rate for products instead of a defining minimum energy performance standard (MEPS). These standards are constantly increased based on the best performance when the defined target year is reached. Due to the fulfilment of standards by individual companies, the Top Runner programme provides more incentives and motivation for product design changes than an industry-wide mandate (Bunse et al. 2007, p.6). Another innovative element of the Top Runner programme is its use of energy consumption efficiency in corporate average as central measurement for evaluation (“average standard value system”). Hence, individual products are not asked to meet the Top Runner standards but the performance of all products sold by an individual manufacturer in the target year (Kimura 2010, p3). With regard to impacts on energy consumption this feature may be criticised as it could undermine the set standards when individual products are concerned.

Another innovative element is the integration of additional policies and measures like labels, awards and incentives to a comprehensive policy package.

Several potential improvements are mentioned in the literature about the Top Runner programme:

Massive over-compliance has occurred with some product groups possibly resulting in potentials to set effective incentives being spoiled. In these cases, the standard-setting procedures should be revised and improved to ensure optimal incentives for the companies to guide the processes of product innovation and market diffusion in an effective way (Nordqvist 2006, p. 29).

Another possible improvement is related to the information base of the instrument, which is not sufficient to properly picture positive environmental impacts of the programme. As it is supplier-oriented, set targets are related to product performance and not defined in terms of energy savings. Therefore, they do not allow estimations about net energy saving impacts. Markets in Japan are informed through updated product catalogues, relating to available models in terms of their Top Runner performance, published twice a year. However, data about individual sales by manufacturers are confidential and although the regulator must collect such data, as they are needed for their evaluation, this data is not publicly accessible (Nordqvist 2006, p.20). Provision and synthesising information could improve evaluation of the programme and thereby lead to improvements (Nordqvist 2006, p.16).

A further possible improvement could be to strengthen the involvement of consumers in order to ensure extending the programme’s impact to the use-phase of appliances (Naturvårdsverket 2005, p. 57). This includes actions to further improve the popularity of the e-Mark scheme as well as the provision of guides, which explain how users can use appliances in an energy-efficient way.

Structural preconditions of the Top Runner programme are mainly related to the capacity of the government to implement all relevant actions. On the one hand, an agency or another institution is necessary to conduct required measuring and evaluation/monitoring activities (including an independent test procedure). On the other hand, the availability of governmental budget for all programme activities needs to be ensured.

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

As the Top Runner programme is a dynamic instrument that needs revision on a regular basis, an agency is needed which is in charge of this task and comes with appropriated capacities. In Japan, the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy establishes, submits, revises standards and determines their coverage with regard to product groups (Nordqvist 2006, p9-10).

Funding

The programme is funded by the government. Information to calculate the overall costs of the Top Runner programme is not available. In general, costs are expected to be rather low. However, costs resulting from linked activities such as labelling, green procurement and tax relief programmes need to be considered as they add to the success of the Top Runner programme (Nordqvist 2006, p.9 and 24).

Test procedure

A test procedure is necessary to calculate the standard energy consumption and to define the Top Runner energy efficiency target standards.

Quantified targets

The Top Runner programme defines quantitative measures, which are set as standards and need to be achieved by individual manufacturers in a certain time period. Quantifications of targets depend on the character of the appliance in focus, the best available technology in the market in the respective product group and the potential innovation process and diffusion expected in the market. No quantified targets are defined for number of participants or total annual energy savings (Nordqvist 2006, p.7). For example; the energy efficiency of microwave ovens was expected to improve by about 8.5% from the fiscal year 2004 to 2008 (METI 2010, p.44). For other product groups please see the next table:

| Product category | First cycle | Second cycle | |||

| Target year | Expected improvement (%) | Realised improvement (%) | Target year | Expected improvement (%) | |

| TV | 1997/2003 | 16.4 | 25.7 | - | - |

| VCRs | 1997/2003 | 58.7 | 73.6 | - | - |

| Air conditioners | 1997/2004 | 66.1 | 67.8 | 2005/2010 | 22.4 |

| Electric refrigerators | 1998/2004 | 30.5 | 55.2 | 2005/2010 | 21 |

| Electric freezers | 1998/2004 | 22.9 | 29.6 | 2005/2010 | 12.7 |

| Vending machines | 2000/2005 | 33.9 | 37.3 | 2012 | 33.9 |

| Fluorescent light equipment | 1997/2005 | 16.6 | 35.7 | 2006/2012 | 7.7 |

| Copying machines | 1997/2006 | 30.8 | 72.5 | - | - |

| Computers | 2001/2007 | 69.2 | 80.8 | 2007/2011 | 84 |

| Magnetic disk units | 2001/2007 | 71.4 | 85.7 | 2007/2011 | 76 |

| Electric toilet seats | 2000/2006 | 10 | 14.6 | 2006/2012 | 9.7 |

Source: METI 2010a; Siderius & Nakagami 2012, p. 6

Actors responsible for design

The Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (governmental agency) is the regulator of the programme on behalf of the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) (ministry).

For the development of top runner standards, a committee (the Energy Efficiency Standards Subcommittee) get together with academic, industry, consumer and government representatives.

Actors responsible for implementation

The regulator of the programme is the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (governmental agency).

Monitoring

Prior to the target year no formal monitoring is conducted, although the publication of statistics on the energy efficiency of individual products is required. The Agency of Natural Resources and Energy collects data on achievements from manufacturers of each product group (Naturvardsverket 2005, p36). However, monitoring issues do not seem to be very transparent. It is known that monitoring activities for internal purposes do occur within industrial sector organisations, but the communication of timing and findings is restricted (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency 2005).

Evaluation

Evaluation of the Top Runner standards is conducted when the target year arrives. Information, which was collected during the compliance phase, is cross-checked with the Top Runner standards defined at the beginning. This information helps to evaluate and revise the programme’s outcomes and to identify necessary refits (Naturvadsverket 2005, p.36).

Two evaluations by Nordqvist (2006) and Swedish Environmental Protection Agency 2005 (2005) were published. Another evaluation by METI (2010) illustrates some specific details of the Top Runner Target Product Standards.

For further information see references.

Sustainability aspects

Furthermore, the Top Runner programme strengthens the international competitiveness of companies involved due to their improvements in terms of technology and reputation compared to their competitors.

Other sustainability effects are not covered by the Top Runner programme.

Co-benefits

Co-benefits related to the Top Runner programme are solely of an indirect nature. The growing share of more energy efficient devices reduces the energy demands of households and thereby makes more budget available in real terms. In addition, the emissions caused by power generation and impacts on climate change is reduced similar to other environmental damages (Naturvardsverket 2005, p.55).

In Japan co-operation between regulator and industry is traditionally far-reaching. This is why the Top Runner programme enjoyed high acceptance among manufacturers and barriers related to competing interests have been very limited (Nordqvist 2006, p17). However, the high involvement of companies in the setting of the Top Runner standards can also be perceived as a barrier to implementation as it can be one reason for the effective over-compliance, which was identified as one of the weaknesses of the programme and indicates that standards may have been set too low and therefore too easy to meet. Another reason for over-compliance could have resulted from the government lacking knowledge about the potential of technological innovations and market diffusion, which led to insufficient standards and thus to wasted potentials of the instrument.

Ex ante estimates of energy savings from the Top Runner programme are scarce. Nordqvist calculated savings of over 200 PJ (55 TWh) by 2010 for the residential sector. Nordqvist has doubts about these figures, as the baseline for them is not clear (Nordqvist 2006).

Target year

Target fiscal years are set for every single product group depending on market and product specifications of the product group.

Since its introduction, the Top Runner programme has steadily realized advantageous effects with regard to improvement in energy efficiency. The energy efficiency improvements made have exceeded initial expectations in each product category on which the standard was based.(METI 2010, p. 8-9).

The most recent publication of METI (METI 2010a) indicates that initial energy efficiency improvements for 13 product groups (including transportation) were expected to reach 35 per cent in the period from the base year to the target year (5-10 years). The effective achievements for the same period and products amounted to 48 per cent and thereby outplayed estimations indicated by the Top Runner programme (METI 2010, p.9). See the next table for a summary overview. The improvements are based on market data as supplied by manufacturers and importers.

Siderius & Nakagami calculated energy savings based on available evaluations (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency 2005; METI 2010). They used the METI data (see the next table) and calculated savings for 2009 “where all products in the stock have been replaced by more efficient products in accordance with the Top Runner standards. These savings are conservative estimate […]” (see the table in the summary section) (Siderius & Nakagami 2012). “In total , the savings contribute between one sixth and one fourth of the national energy efficiency saving target (Siderius & Nakagami 2012)”.

An example for this calculation is the product group “refrigerators”: “The sales-weighted average energy consumption in 2005 was 572 kWh/year and the average energy consumption in 2010 was 452 kWh, assuming that the distribution of sales over the various categories will not change, resulting in an improvement of (572-452)/x100%=21%” (Siderius & Nakagami 2012, p.4).

| Product category | First cycle | ||||

| Target year | Expected improvements (%) | Realised improvements (%) | Target year | Expected improvements (%) | |

| TV receivers (CRTs) | 1997/2003 | 16.4 | 25.7 | - | - |

| VCRs | 1997/2003 | 58.7 | 73.6 | - | - |

| Air conditioners | 1997/2004 | 66.1 | 67.8 | 2005/2010 | 22.4 |

| Electric refrigerators | 1998/2004 | 30.5 | 55.2 | 2005/2010 | 21 |

| Electric freezers | 1998/2004 | 22.9 | 29.6 | 2005/2010 | 12.7 |

| Vending machines | 2000/2005 | 33.9 | 37.3 | 2012 | 33.9 |

| Fluorescent light equipment | 1997/2005 | 16.6 | 35.7 | 2006/2012 | 7.7 |

| Copying machines | 1997/2006 | 30.8 | 72.5 | - | - |

| Computers | 2001/2007 | 69.2 | 80.8 | 2007/2011 | 84 |

| Magnetic disk units | 2001/2007 | 71.4 | 85.7 | 2007/2011 | 76 |

| Electric toilet seats | 2000/2006 | 10 | 14.6 | 2006/2012 | 9.7 |

Source: METI 2010a, p. 9; Siderius & Nakagami 2012, p.6

Costs are expected to be rather low. However, costs resulting from linked activities such as labelling, green procurement and tax relief programmes need to be considered as they add to the success of the Top Runner programme (Nordqvist 2006, pp.9 and 24).

Depending on the requirements set by the Japanese government it can be expected that the policy is cost-effective.

Top Runner programme – Developing the World’s best Energy-Efficient Appliances (Revised Edition/Mar. 2010)

Accessible online at:

www.bigee.net/s/7yezdi

(Japanese version)

www.bigee.net/s/fib6yw

(English version)

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy