The Market Transformation Programme (MTP) in the United Kingdom (UK) provides independent and objective information to policy-makers with the aim of developing products and services which use less energy and protect the environment. The MTP supports the development of policy targets and roadmaps and assists the implementation of concrete policies like minimum energy performance standards and labelling schemes (MURE 2011). Therefore, MTP develops policy recommendations working in both directions of the appliance spectrum (cutting out least-efficient and promoting highly efficient devices). MTP and the UK government want to form product policies on a broad consensus, thus the programme has close ties with and embraces the EU, business stakeholders as well as consumer organisations. British product policy, which includes the MTP, has been estimated to save 29.1 TWh in annual final energy demand by 2020 in all sectors.

The Market Transformation Programme (MTP) is a programme that collects information and conducts research on various energy using devices, most of which are domestic appliances. “The main activity and value of the MTP is the development and maintenance of a public domain evidence base (MURE 2011)”. Based on data, which is collected in co-operation with various stakeholders (manufacturers, consumer testing organisations), MTP develops policy briefings for decision-makers comprising the current and future stock of a respective device as well as projections about future energy consumption. Moreover, MTP sets roadmaps for market transformation towards environmentally better products, and develops policy recommendations such as (tightening of) minimum energy performance standards, energy labels, voluntary agreements and the like. Furthermore, methodologies were established to rank the performance of energy-using products (MURE 2011). Embracing all relevant stakeholders is important in order to increase the acceptance of the programme and its resulting policies. In the end, however, it is up to policy-makers to implement respective recommendations.

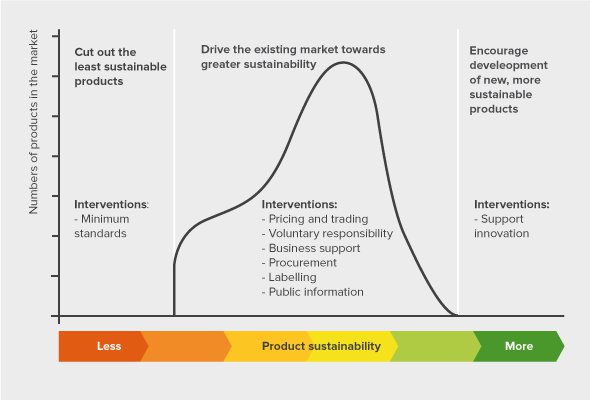

The Department for Environment, Food and Agriculture (DEFRA) introduced the Market Transformation Programme in 1998 as a part of their product policy, which works at both ends of the product spectrum. On the one hand, it attempts to cut out least efficient appliances while encouraging the promotion of highly energy-efficient devices on the other hand (see the next figure).

Today, it is closely linked to the development and implementation of the process following the Ecodesign Directive of the European Union (EU).

The programme is rather loosely affiliated to DEFRA. Although the department funds the programme, infrastructure and expertise are within so-called contractors, e.g. consultancies. Their experts have some direct or indirect links to the appliance-manufacturing business, so they know the weak spots in terms of energy efficiency of particular products.

It was very important for the British government to have an objective (and impartial) instrument available to promote energy efficiency in the appliance market especially because it has always avoided unnecessary market intervention. Now, intervention is based on scientific and transparent facts. While the programme is also open for business stakeholders to voice their opinion, interests and concerns about potential future regulation, it also functions as an interface between UK and EU policies. For example, if the EU tightens its European Energy Label, MTP can contribute to such regulation offering advice regarding certain products and, in return, it is able to find ways how to implement regulation into UK law. 2006 also showed that the programme is internationally oriented. Together with the Chinese government, MTP attempted to improve the product policy in China.

The programmes in the USA, China, Australia, the EU with its Ecodesign policy, and many other countries to develop Minimum energy performance standards and Energy labelling for energy-using products follow a similar roadmapping and target-setting process but are not always based on such detailed and continuous scientific and data assessment as in the UK.

Sweden is known to have been conducting market transformation programmes since the late 1980s. The Swedish Department of Energy Efficiency “co-ordinated, designed and financially supported” these programmes (Neij 1999, p.1).

Between 1970 and 1997, the total annual energy consumption in the UK residential sector rose from 36.9 mtoe to 44.8 mtoe, i.e. 18%. In particular, the energy use for lighting and appliances doubled in that period (1970: 2.7 mtoe; 1997: 5.9 mtoe). (The Guardian 2011). One reason is the increasing ownership level of nearly all kinds of domestic appliances (For an overview of the current appliance stock, one can refer to DEFRA 2009 a). Furthermore several products of these product categories sold in the UK were less energy-efficient than those sold in other European countries around 1994 (DEFRA 2009a, p. 218).

Another aspect has also to be kept in mind. The British government favours economic instruments over market intervention by regulators. Thus, only where “market failure is obvious and economic instruments are stretched to their limits”, does the state intervene (Rubik & Scheer 2005, p. 58). That is why the UK government created the MTP in 1998, which can be regarded as a highly scientific market-analysing instrument.

Moreover, product policy has traditionally been relevant in the United Kingdom. However, the 1970s and the 1980s were shaped by policies putting labour and health concerns in the very forefront of such policies. Since the 1990s, environmental components have been integrated into the product policy (Rubik & Scheer 2005, p. 50).

In other words, the UK wanted to a) decelerate ever-increasing energy-consumption and b) change its role as a backbencher (Rubik & Scheer 2005, p. 61) in environmental policy as compared to more progressive countries at that time. This led to the formation of the MTP, a scientific instrument gathering objective information in order to intervene in the market where and when necessary.

It is a national policy, but with close links to the Ecodesign process at the supranational EU level.

The core goal of the MTP is, as its name states, to transform the appliance market. In order to reach this goal, MTP has one core task: research. Based on this research, which in general is fine-tuned with business stakeholders, MTP gives policy recommendations. Policy-makers rely on “evidence on impacts and trends arising from products across their life cycles” (MURE & AEA 2011, 1). MTP develops Product Strategy Guides and Policy Briefs, “which set out the measures required to reduce the energy consumption of appliances” (IEA NAa). Available are so-called Government Standards Briefing Notes (GSBNs). They are designed for almost all appliance categories and, thus, form the basis for Product Strategy Guides and Policy Briefs (GSBNs are available at www.bigee.net/s/u12c67). In general, those notes comprise background information (instead of policy recommendations) about the number of households owning the appliance (“Ownership & Stock”), sales figures (“Sales”) and consumption habits over its life-cycle (“Usage & Lifespan”). These data sheets also give stock and sales projections until 2030. The document “Saving Energy Through Better Products and Appliances” summarises MTP’s findings and discusses goals to be reached by 2030 (DEFRA 2009).

Moreover, the programme promotes voluntary industry agreements and government procurement (DEFRA 2005, p. 11).

Most of the activities done by the MTP include co-operation and information exchange with business stakeholders. Doing this, MTP can be regarded as a platform where business actors can bring in ideas, concerns and interests with respect to certain policies (DEFRA 2009, p.24).

The MTP is an interface between various other policies. First of all, it supports the British government in translating different European eco-directives into UK regulation. The most important of these is the Ecodesign directive, passed in 2005 and revised in 2009. It is the basis for setting minimum energy performance standards and creating mandatory comparative labelling schemes for energy-related products in the EU. As another example, in 2000 the European Union agreed on introducing the Energy Star, a voluntary product label, into the European market. “MTP provides input into ENERGY STAR specification revision process” (DEFRA NA).

While MTP rather works in the background, the Energy Saving Trust (EST) provides information on energy-efficient appliances to consumers more actively. The EST provides useful energy saving advice and supports buying-decisions via a database with the most energy-efficient appliances available (the database can be accessed www.bigee.net/s/yjyxmt).

Furthermore, electricity and gas suppliers in Great Britain have Energy saving obligations. As a part of the programmes to achieve their energy-savings targets, they have offered grants for the purchase of energy-efficient refrigerators. The information from the MTP was useful for the government when defining eligible appliances and the deemed amount of energy savings allowed for each appliance purchase supported by the schemes.

The MTP also supports the product procurement activities of the UK government. The central government, including its departments and their related agencies, must meet so called Government ‘Buying Standards’. These simplify the procurement process for over 50 different products by providing procurement staff with “straightforward” tender specifications and by “enabling more suppliers to develop products that meet the standards” (DEFRA NA b).

The policy includes innovative elements.

MTP publishes information material on various appliance categories. This information is necessary for regulators to make reliable decisions. It appears to be innovative that product “reports” give product sales projection and consumption patterns for the next decades. “The measurement of impact is based upon assumptions about sales and product, the degree of use of that product, its performance and the degree of ownership” (House of Lords 2005a). For some products MTP also co-operates with consumer testing organisations in order to find out about “how the device is used by the consumer rather than how the device performs under a test standard” (House of Lords 2005a.

MTP can be regarded as a perfect actor to consult policy-makers in such a way that market actors are not overburdened by future regulation. Probably, the nature of the contractors also attracts business stakeholders to co-operate closely within the MTP. It can be regarded as a forum in which market actors can and shall voice their opinion and share their expertise on certain product categories.

There are possible actions for optimising the policy. In 2005, the network of MTP experts was insufficiently funded. Regular meetings were not possible. Face-to-face meetings were only held “when it is important to have that meeting” (House of Lords 2005). Even the infrastructure for MTP lay within the contracting organisations. In order to improve working conditions and, thus, facilitating the work of the programme, it seems necessary to provide some additional funding to the programme.

MTP does not have a website clarifying its organisation, its host organisations, its workflow or its goals.

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement the UK Market Transformation Programme

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

The MTP is managed by the Department for Environment, Food and Agriculture (DEFRA) and has funded various contractors so that these provide staff with valuable expertise in appliance technology and of the appliance market to the MTP. The lead contractor is AEA, working alongside with Consumer Research Associates (MURE 2011).

Funding

MTP is a subordinate to DEFRA, which has a budget of around £2.3 billion annually. In 2010, its budget was cut by £700 million (The Guardian 2010). According to a specialist consultant of AEA Technology, the MTP Programme has a budget of about £500,000 (€620,000) (Drummond NA).

Both, the global rise in energy prices and increasing consumption of British households (18% between 1970 and 1997; The Guardian 2011) were key factors to decelerate this consumption pattern.

In 1998, DEFRA implemented and funded the MTP, evolved from the Energy Efficiency Best Practice Programme with the aim of supporting the development and implementation of policies and measures on sustainable products. The MTP works with a consortium of impartial, external (non-governmental) experts to reduce environmental impacts through better product design (MURE 2011). The following activities were undertaken:

methodologies were established to rank the performance of energy-using products

energy labels were introduced and information provided

efficiency standards for public procurement were introduced and introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by the EU was supported with UK data

route maps were set for market transformation

In recent years these activities were expanded and include: life cycle assessments, information about consumer choices, and public procurement and working with stakeholders to harness their expertise (MURE 2011).

While the MTP appears to be an integral part of Britain’s product policy, its policy recommendations e.g. regarding labels and standards do not have to be implemented automatically. Policy-makers have the last word in that process. However, MTP can also facilitate voluntary agreements between manufacturers; it goes without saying that such initiatives do not require government consent.

Quantified target

The policy has a quantified target. As stated in UK’s National Energy Efficiency Action Plan, Britain’s product policy (which is much more than the MTP) is supposed to save:

In the residential sector:

2010: 1.4 TWh/yr

2016 8.5 TWh/yr

2020: 18.8 TWh/yr

In the commercial, industrial, and public sectors:

2010: 1.6 TWh/yr

2016: 6.0 TWh/yr

2020: 10.3 TWh/yr

International co-operations

The MTP co-operates with the European Commission. Not only because the department that funds MTP i.e. DEFRA, is responsible “to inform and respond to policy developments at European Commission level” (House of Lords 2005) but also because in the EU, MEPS and mandatory comparative energy labels are created at the EU level and not by an EU Member State alone.

The programme contributes to other initiatives such as the Energy Star label, a voluntary product label originally from the United States, which was introduced in Europe in 2000.

Between 2006 and 2007, DEFRA joined with China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) “to harmonise and converge product performance specifications at a global level, fostering the development of efficient products at a lower cost.” As China has been the “manufacturing base in the world”, the UK tries to support the Chinese government to make electrical appliances produced in China more energy-efficient (IEA NA).

Actors responsible for design

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA)

Evaluation

Every two years an assessment is made on progress over the previous target period. The energy savings are calculated in accordance with Green Book policy appraisal guidelines (MURE 2011).

Design for sustainability aspects

The MTP aims to develop products using less energy but also less water, and other resources. In recent years the programme developed evidence “on impacts and trends arising from products across their life cycle (Life Cycle Assessments)” (MURE 2011).

The following barriers have been experienced during the implementation of the policy

Based on a hearing of MTP experts, the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology felt that “MTP has a low profile in wider manufacturing industry” (House of Lords 2005b).

Due to limited funding, MTP does not have its own infrastructure (e.g. secretariat or a similar central planning body). Higher levels of funding would be an obvious solution to this problem.

The target years are 2010, 2016 and 2020.

Concrete figures in energy savings/year

From the 2011 update to the UK’s 2007 National Energy Efficiency Action Plan estimated annual energy savings as a result of the British Product Policy were calculated (DECC 2011, p. 4):

In the residential sector:

2010: 1.4 TWh/yr

2016 8.5 TWh/yr

2020: 18.8 TWh/yr

In the commercial, industrial, and public sectors:

2010: 1.6 TWh/yr

2016: 6.0 TWh/yr

2020: 10.3 TWh/yr

See the next tables, in order to find estimations on energy-consumption projections for some appliance types covered by MTP.

| 2009 Current (GWh) | 2020 LCTP/Reference Scenario (GWh) | 2020 Policy scenario (GWh) | 2009 CO2 emissions (MTCO2) | Annual CO2 emission savings at 2020 (MTCO2) | |

| Television | 8,350 | 7,320 | 5,390 | 4.18 | 0.73 |

| Power Supply Units | 5,010 | 7,580 | 7,130 | 2.50 | 0.17 |

| Set top boxes | 3,690 | 4,580 | 1,930 | 1.85 | 1.00 |

| Video recorder | 3,100 | 780 | 530 | 1.55 | 0.10 |

| Game consoles | 630 | 1,630 | 1,630 | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| TOTAL | 20,800 | 21,900 | 16,600 | 10.39 | 1.99 |

LCTP: Low-carbon transition plan

Source: DEFRA 2009, p. 37

| 2009 Current (GWh) | 2020 LCTP/Reference Scenario (GWh) | 2020 Policy Scenario (MtCO2) | 2009 CO2 emissions (MTCO2) | Annual CO2 emission savings at 2020 (MtCO2) | |

| Cold | 14,500 | 10,500 | 9,630 | 7.24 | 0.31 |

| Laundry | 11,030 | 12,200 | 11,400 | 5.51 | 0.32 |

| Dishwashers | 3,220 | 3,450 | 3,150 | 1.61 | 0.12 |

| TOTAL | 28,700 | 26,100 | 24,200 | 14.37 | 0.75 |

LCTP: Low-carbon transition plan

Source: DEFRA 2009, p. 46

Information rather revolves around the UK’s broader product policy instead of MTP. The costs are estimated to be at around £15 million (€ 18.6 million) by 2030 (DEFRA 2009).

DEFRA (2009) estimates its product policy to achieve cost savings of £41 million (€50.9 million) and, hence, net benefits of £26 million (€32.3 million) between 2009 and 2030.

Between 2009 and 2030, DEFRA (2009) assumes investment of £15 million (€18.6 million) and achieving cost savings of £41 million (€50.9 million). Consequently, the cost:benefit ratio is 1:3 for Britain’s overall product policy.

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy