“Energy labels move the market towards highly energy efficient products which is a major contribution to reaching Europe's energy efficiency, competitiveness and climate change goals. At the same time, they save money for consumers” (European Union Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger). The European mandatory comparative label aims to inform consumers about the energy efficiency of the products and other product characteristics. The label was very successful. Whenever a product was labelled, the inefficient appliances seemed to rather quickly disappear from sale.

The European Union (EU) adopted a categorical system of comparative energy labelling in 1992, wherein most of the products are assigned to one of 7 different energy classes from A (green) - the most energy-efficient, to G (red) - the least efficient. The label also shows the annual energy consumption under standard use conditions. Manufacturers must provide the label and retailers must display it on appliances and show the label class in advertisements. The idea behind the scheme is that if purchasers were better informed, they would tend to buy appliances, which – for the given service performance - were more energy-efficient, cost less to run and have a smaller environmental footprint.

Products currently covered by an implementing regulation are: refrigerators, dishwashers, washing machines, dryers, ovens, air conditioners, household lamps and televisions (since 2010). Further products are likely to follow like: boilers, water heaters, household tumble driers and vacuum cleaners. It is estimated that with an extended product range, the energy label could lead to savings of some 22 MTOE per year by 2020, corresponding to annual emission reductions of about 65 Mt of CO2.

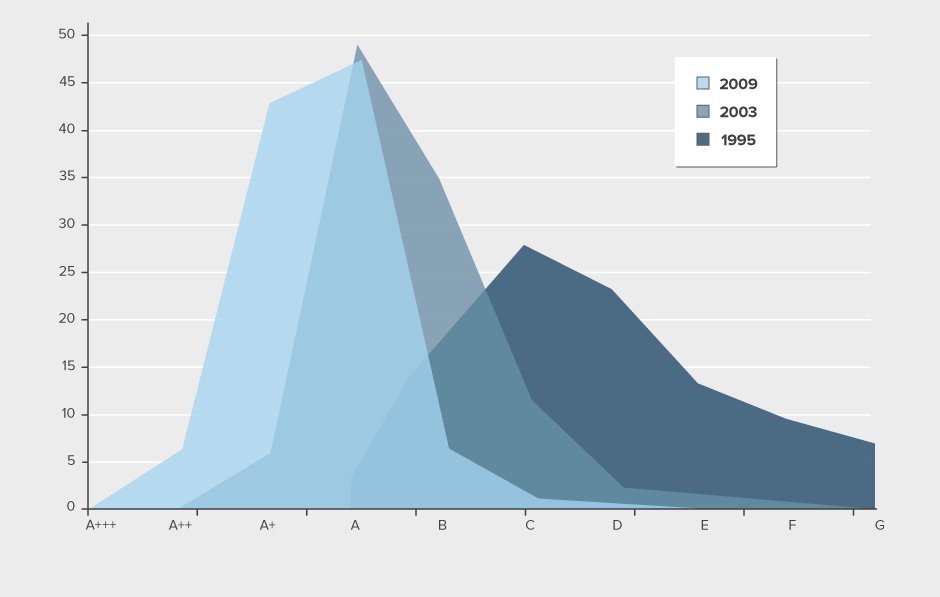

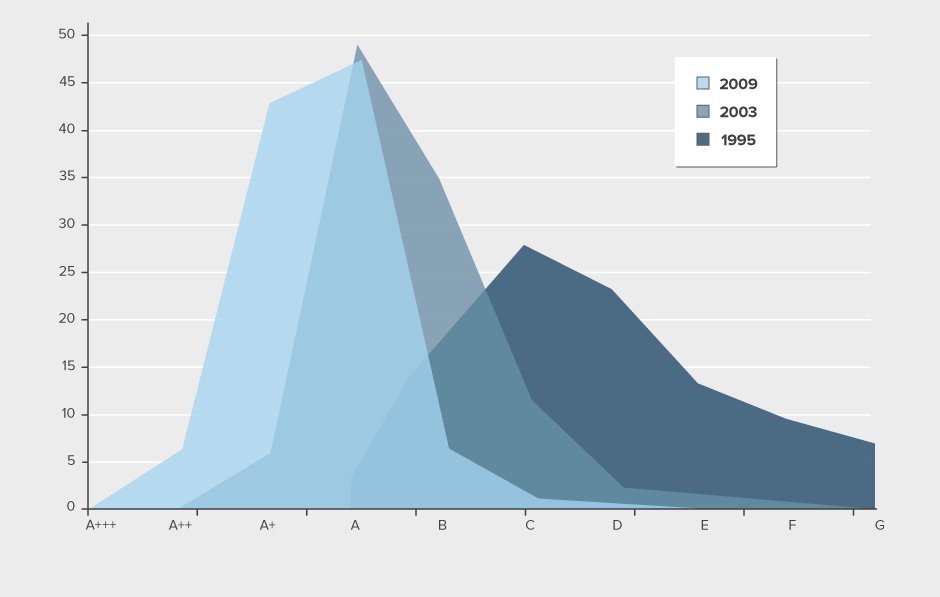

Whenever a product was labelled, the inefficient appliances seemed to rather quickly disappear from sale, and A and B rated products started to dominate the market. Being unable to decide on moving the A to G scale to higher energy efficiency levels, in 2003 the EU had to subdivide the A category into three classes for fridges and freezers: Standard A, A+ and A++. In 2010 and 2011 for refrigerators, washing machines, air conditioners and dishwashers the efficiency classes were changed to a scale of D to A+++.

The Energy Labelling Directive has had, and still has, a major role in pulling the market towards more energy-efficient products. The label affects all products covered by an implementing directive and put on the internal market, irrespective of whether they are manufactured in the EU or in a third country. Labelled products require manufacturers to provide energy efficiency information in a standard format to be made publicly available. Companies putting most energy-efficient appliances on the European market increase their chance of being competitive on other markets also, as the demand for energy efficient products steadily grows.

Substantial technical innovations have taken place for all the relevant product categories during the last decade. It was estimated that energy labelling has contributed to annual energy savings in the order of 3 MTOE corresponding to emission reductions of some 14 Mt of CO2 annually over the period 1996-2004 (European Commission 2008). These energy savings are generally cost-effective for consumers i.e. they reduce the overall life-cycle costs of appliance purchase and energy over the average appliance ‘lifetime’. The EU Energy Labels have been a main institutional framework for innovations and they have constituted the platform for technology improvements and competition in the European market. Between 1995 and 2008, there was a shift in the most sold energy classes from D and G to class A appliances, in most European countries.

The label is well-known and trusted among European consumers, and it is actively used in the households’ decision-making processes (Ipsos MORI 2008). For example a German survey (BMU 2008) by the Ministry of the Environment has found that the EU label is known by 84% of the German population. 64% of the respondents said that the label plays a role during the buying decision. It provides useful and comparable information, allowing them to consider investing in better performing appliances in order to realise savings in taking into account the running costs.

In 1992, there were widely differing energy efficiency levels for household appliances in the then 12 Member States. Also, energy efficiency of appliances was not easily comparable for consumers. For example: in Germany, the law required manufacturers to provide information in the user manual, but it was given in kWh/24 hrs or kWh/washing cycle, not in kWh/yr.

The current political framework for the Energy Labelling Directive is the European (Action) Plan for Energy Efficiency (2006/11), which mainly influences the political surroundings. The major scope of the action plan is to intensify the process of realising more than the 20% estimated savings potential in EU annual primary energy consumption by 2020. This will contribute to the EU’s wider objectives of increasing the competitiveness of the EU economy, improving energy security and reducing harmful emissions in line with the EU’s Kyoto commitments.

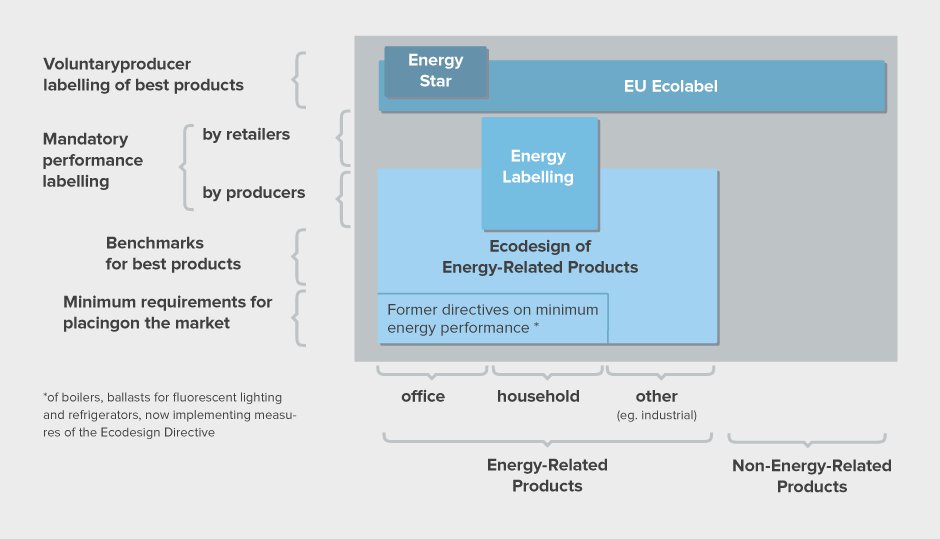

The energy label is also influenced by the Ecodesign Directive. For some product groups, requirements were set in accordance with the minimum energy performance standards (MEPS).

Besides the political surroundings, the market (stock data, sales, market developments, technology possibilities) of every product group differs and therefore every product group has its own individual situation at the outset. In general, the product groups are characterized by a few market-dominating manufacturers.

The purpose of the EU Energy Label is two-fold. It informs potential purchasers of the energy consumption (and other emissions e.g. noise) of the appliances on offer, so consumers can take account of this and of the resultant running costs before making purchase decisions. The demand pull created in this way, by the directive, also incites manufacturers to produce more energy efficient appliances.

The EU energy label is a supra-national P&M and covers all 27 Member States of the European Union.

The P&M covers appliances (in detail: dishwashers, washing machines, televisions, refrigerators and freezers, dryers, ovens, air conditioners) and household lamps.

In addition to the MEPS, which eliminate the most energy-consuming appliances, the labelling Directive has had and still has a major role in pulling the market towards more energy-efficient products. The Directive 92/75/EC, revised in 2010 to the Directive 2010/30/EU, and its delegated regulations provide consumers with the means to identify the most energy-efficient appliances i.e. A+++ or A++ in the ranking of a scale of A+++ to D or respectively to A in the ranking of a scale from A to G.

Different calculation methods for the energy label were defined for every product group. Usually the EEI – the energy efficiency index - is used to calculate the efficiency classes. The calculation of the EEI for refrigerators is exemplarily illustrated below. The definitions of the calculation methods can be found in the product-specific regulations.

For the calculation of the Energy Efficiency Index (EEI) of a household refrigeration appliance model, the annual energy consumption of the household refrigeration appliance is compared to its standard annual energy consumption.

The EEI is calculated and rounded to the first decimal place as:

EEI = AEc/SAEc x100 where

AEc = annual energy consumption of the household refrigeration appliance

SAEc = standard annual energy consumption of the household refrigeration appliance (usually derived from the average energy consumption levels of appliances sold in the market before introduction of the energy label)

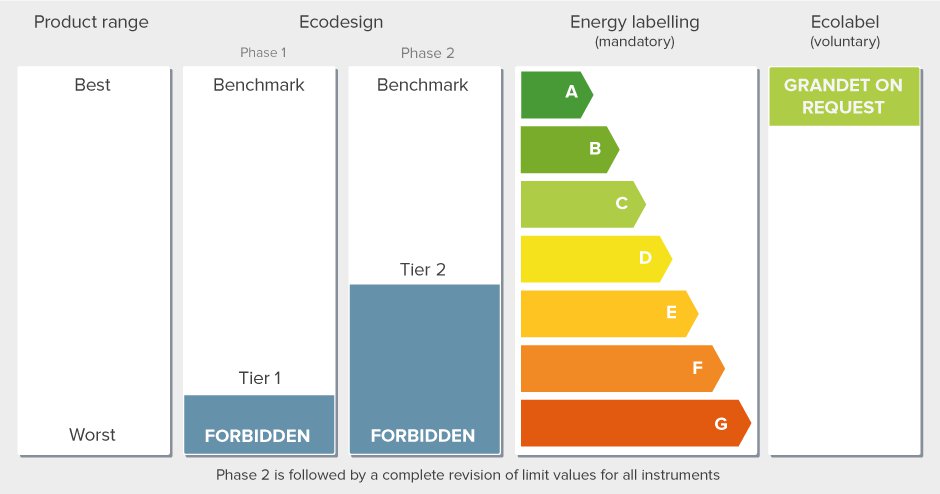

An important aspect for the functioning of an energy labelling scheme is the synergy complementarities and possible overlap with other instruments. The next two figures illustrate the complementarities and synergies between ecodesign, ecolabel and energy labelling. While ecodesign cuts the less efficient products from the market, the voluntary ecolabel grants a “best in class” label for the upper end products (corresponding normally to an ‘A’ class in the energy labelling classification). Energy labelling complements the picture in providing compulsory comparative information on energy performance between these two extremes. It also pushes manufacturers to invest in more efficient products in order to shorten the path from R&D to mature products for markets.

Furthermore, the European energy labelling scheme has helped, for example as in the Netherlands and Italy, to develop financial incentive schemes. The label classes make it easy for programme developers to define the most energy-efficient appliances that are promoted via the incentives, and for retailers and consumers to identify the products eligible for the incentive. For example the Dutch Energiepremieregeling (Energy Premium Scheme) has been successful in transforming the market for energy-efficient household appliances in the Netherlands with the help of the EU energy label.

The P&M includes innovative elements by including the interests of consumers explicitly into the development of the instrument (e.g. a consumer survey was run during the preparatory study of the EU energy label and the ecodesign directive). The label is also part of an innovative package.

The interaction of the energy label with financial incentive schemes (e.g. the Netherlands, Italy, the UK) and with the European ecodesign directive (same preparatory study and impact assessments) is well founded and innovative.

There are possible actions to optimise the P&M itself.

The instrument could be improved with tighter tolerances in test standards and reinforced market surveillance.

Currently the EU label does not allow the provision of product information such as an estimate of the annual running cost in monetary terms (as for example: in the USA) or carbon footprint. Opening this possibility could significantly improve the energy label’s impact.

Furthermore the market share of A labelled appliances (for types of appliances where A is the most energy-efficient class) is already very high for some product groups. A co-ordinated dynamic revision of the regulation in co-ordination with the market and sales is needed.

The policy package can be optimised, too.

The EU Energy Label is in accordance with the Ecodesign Directive and voluntary endorsement labelling schemes. Furthermore the instrument could ideally interact with incentives (as already occurred in The Netherlands for example), information, and public procurement programmes. Some efforts to use the information of the label and the energy efficiency classes for other such measures already exist, but they could be extended much further (e.g. by co-ordinated financial incentive programmes in all or many EU Member States).

Structural pre-conditions are a test procedure, an agency and a funding scheme.

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

An agency or similar organisation is necessary to guarantee market surveillance and monitoring and to ensure compliance with the manufacturer obligations to correctly declare the energy consumption and the retailer’s obligations to correctly display the energy label.

Funding

There is no large funding scheme necessary, except for the development and update of the scheme and for the compliance monitoring.

Test procedure

A test procedure is necessary to calculate the standard energy consumption and to define energy efficiency classes. The EU’s test procedures are based on IEC standards. Energy efficiency levels are calculated for each appliance according to its consumption and its product characteristics (volume, size etc.)

Before the European Commission prepares a delegated regulation (previously: implementing directive) for one type of appliance, it conducts a technical economic study, which looks into the range of energy and service performances available among products on the market offering similar functionalities, the potential for improvement, and the related costs. This phase is co-ordinated with the MEPS process under the Ecodesign Directive. Extensive stakeholder consultation with manufacturers, retail trade, environmental and consumer NGOs and others, took place during the preparatory study in form of bilateral meetings, complemented with public stakeholder consultation through the internet and a dedicated stakeholder workshop. The Commission is involved in formal regulatory dialogue with its main trading partners and with international organisations on issues such as the harmonization of measurement methods/standards, benchmarking and other elements directly linked to the setting of delegated regulations. After impact assessment and inter-service consultation, the Commission gathers the opinion of the energy label directive committee (made up of representatives from the Member States) operating under the regulatory procedure with scrutiny by the European Parliament, and the Commission then adopts the delegated regulation following the normal procedures. The delegated regulations are directly applicable in all Member States (European Commission 2008). In 2003 and 2010, according to the rapidly rising market shares of some product groups, the additional energy efficiency classes A+, A++ and A+++ were introduced. Some smaller changes were made as well, to take into consideration internet and e-commerce.

Quantified target

The P&M, as such, has no quantified target. It contributes to the EU’s overall target of saving 20 % of primary energy between 2005 and 2020 compared to the projected 2020 energy consumption.

Co-operation of countries

The EU Energy Label was introduced in all 27 Member States. According to Article 1: “The Directive establishes a framework for the harmonisation of national measures on end-user information”

There are different co-operations with other countries, which already introduced a similar energy label or plan to implement a similar label.

Actors responsible for design

The European Commission, with the final decision by the European Parliament and the European Council (i.e., Member State governments)

Actors responsible for implementation

The Member States’ authorities are responsible for the implementation of the regulation, including both transposition into national legislation and market surveillance.

Retailers/dealers are responsible for the affixing of the label at the point of sales onto the regulated appliances and for the provision of correct information to the consumers in advertisements.

Manufacturers/Suppliers are responsible for measuring and declaring the performance of their models, for holding the technical documentation and for providing the labels to retailers/dealers.

Monitoring

The main monitoring efforts are the random tests carried out to verify correct labelling. Monitoring of the impacts is done by market surveillance carried out by Member State authorities ensuring that the rating on the label is truthful (SEC (2009) 1020 final).

Furthermore, the action can be monitored quite well when counting the sales figures per energy label category. This is left to commercial organisations in the EU.

Evaluation

There have been a number of studies on the impact of the labelling scheme (e.g. Berg, Lisbeth et al. (2009), European Commission (2009), Europe Economics et al. (2007), Lebot, Benôit et al. (2000), Schlomann, Barbara et al (2001), Swedish Energy Agency (2006), Winward et al. (1998)).

Economic benefits and costs were/will be assessed ex ante in accordance with the Ecodesign Directive 2009/125/EC.

The label indicates energy use in (kWh/year) but also other performances, such as noise (in dB(A)) and cooling characteristics for refrigerators and freezers, the water consumption by dishwashers and washing machines or the availability of an on/off button for televisions.

Employment impacts were calculated for different scenarios in combination with MEPS. For household refrigeration appliances the policy scenarios (more ambitious requirements) all give an employment increase of around 10%, creating between 4 000 and 16 000 new jobs more than a ‘business as usual’ scenario (SEC(2009) 1020). According to another source, with the single label, production and the selling of more energy-efficient appliances does not create extra jobs. The extra personnel needed for innovation is marginal on total employment (Atkins 2006).

Several stakeholders have reported insufficient surveillance and enforcement by Member State authorities, both in respect to manufacturers meeting the set requirements and retailers displaying correct information.

A study by ANEC reported compliance problems in some member states regarding label display in the shops and the testing of appliances (ANEC 2007).

The distribution of some A labelled appliances is very high. The dynamic revision of the regulation is not dynamic in co-ordination with the market and the sales.

The added A+ and A++ classes are reported to be confusing by all the consumer organizations (ANEC 2007).

Until now, no great efforts were made to overcome the barriers. The ANEC (2007) study illustrates various options for reducing the barriers.

Considering that the energy label can contribute to making the “right” purchasing decision but is not the only element guiding consumer decision to buy a particular product, it is difficult to assess the impact of a labelling information scheme on the energy efficiency of appliances.

In 2008 it was estimated that with all current policies already in place, a total of 65 TWh to 75 TWh per year could be saved by 2010. It has been estimated that energy labelling schemes and consumer education about them with all covered products could account for about half of the increased take up of more energy efficient appliances, contributing in total to some 35 TWh of energy savings per year (2010) and corresponding to some 3 MTOE of primary energy and some 14 Mt of CO2 by 2020 (European Commission, 2008). The rest of the saving is composed mainly of technological development and MEPS.

Furthermore, for single product groups the potential savings were calculated. For example: for the new label on televisions, it is estimated that a total energy savings potential of 46 TWh by 2020 could be realised. Out of this total potential, it is further estimated that energy labelling could catch about 12 TWh (about 1 MTOE) by 2020, corresponding to emission reductions of 4,8 Mt of CO2. As to lighting, the Ecodesign preparatory studies indicate that general lighting appliances would provide some 75 TWh of savings potential, of which energy labelling could catch some 16 TWh (about 1,5 MTOE) by 2020, corresponding to reduced emissions of 6,4 Mt of CO2 (European Commission 2008).

It is estimated that with an extended product range, the energy label could lead to savings of some 22 MTOE per year by 2020, corresponding to annual emission reductions of about 65 Mt of CO2. More than half of these savings would come from the heating and water heating appliance alone, which have not yet been addressed by the labelling directive. The rest of the savings would come from the upgrading of the existing eight measures and from a new measure on televisions (European Commission 2008).

With full implementation of the current labelling scope plus coverage of all energy-related products, the directive could lead to additional savings of some 27 MTOE by 2020, i.e. 5 MTOE additional savings by broadening the scope to include windows, commercial refrigeration and heating appliances.

The European Union’s mandatory labelling of electric appliances has been an attempt at changing behaviour of consumers as well as of producers/importers, and it has been a definite success in the European consumer market. It is estimated that energy labelling has contributed to annual energy savings in order of 3 MTOE corresponding to emission reductions of some 14 Mt of CO2 over the period 1996-2004 (European Commission 2008).

Furthermore the combined effect of the labelling scheme and the minimum energy efficiency requirements have already led to significant energy savings for single product groups. For example in 1995, refrigerators consumed on average 425 kWh/year. In 2005, they consumed approximately 292 kWh/year, which represents a reduction of about 30% (Ecodesign Preparatory Study Task 2).

There have been a number of studies of the impact of the labelling directive. These track the increased take up of higher efficiency appliances over the past decade. Of all the appliances covered by implementation directives, the impact has been greatest for white goods, particularly refrigerators, freezers and washing machines. The majority of these products sold today carry an A or B rated label or better (i.e. A+ or A++) compared with the majority of products sold in 1994 carrying a D rated label or worse. Recent market data on the share of energy efficient appliances suggests that the EU market for refrigerators is moving towards a higher share of most efficient classes of appliances. The next figure gives an overview of the market development.

The success of the labelling scheme is also demonstrated in the high number of third countries that have adopted a similar label or sometimes an exact copy of the EU energy label.

It is unknown, which share of the overall technical and economic potential has been achieved by energy labelling. However, the European Commission (2008) has estimated that energy labelling schemes and consumer education about them with all covered products could account for about half of the increased take up of more energy efficient appliances due to policy.

The form of the legislation is a regulation which is directly applicable in all Member States. This ensures no high costs for national and community administrations in transposing the implementing legislation into national legislation and ensures timely and harmonised entry into force within the internal market.Although energy labelling and technology development have made further energy savings more challenging in the case of the product groups already labelled, considerable savings can still be reached. Estimated savings of some €3 billion by 2020?? can be reached.

Furthermore, it is estimated that the current directive, including the upgrading and the development of new labelling schemes for new product groups, would help to reach cost savings of €22 billion.

For single product groups, the saving potentials were calculated as well. For the new label on televisions it is estimated that energy labelling could catch about €1,6 billion pa (per annum??) by 2020. For lighting, labelling could catch some €2,2 billion. (European Commission 2008).

No assessment studies on this issue are known to us.

However, the impact assessment performed for each product group under the Ecodesign procedure proves that the level of energy efficiency required for the MEPS is cost-effective for the consumers. In contrast, appliances in the most energy-efficient classes of the energy label may not be cost-effective for all EU citizens.

It can, however, be said that the additional policy cost for the EU energy labelling scheme is small (see above).

Most of the energy efficiency measures are cost-effective. This means that they will result in net money savings for the users, as the reduced electricity costs over the life time of the appliances will be bigger than any additional purchasing cost for the more efficient model. Over recent years, the EU white goods appliances cost less and their efficiency has improved, while keeping the industry sector healthy (though with limited margin) and despite fears by manufacturers that the policy action introduced in the 90’s could have had a negative impact. Instead the "white goods" industry sector acknowledges the added value of the label as a means to differentiate products on the market (European Commission 2008).

In many cases there is a higher manufacturing cost for energy-efficient appliances to manufacturers, which can be passed on to the users or can be compensated by productivity gains. Over the last ten years, the EU white goods manufacturers have become more profitable, appliances cost less, and the efficiency has improved. Overall it can be concluded that energy efficiency measures, and in particular labels, are cost effective for society and reduce CO2 emissions at a negative cost (Bertoldi/Atanasiu 2007).

Considering that the energy label can contribute to making the “right” purchasing decision but is not the only element guiding consumer decision to buy a particular product, it is difficult to assess the impact of a labelling information scheme on the energy efficiency of appliances.

In 2008 it was estimated that with all current policies already in place, a total of 65 TWh to 75 TWh per year could be saved by 2010. It has been estimated that energy labelling schemes and consumer education about them with all covered products could account for about half of the increased take up of more energy efficient appliances, contributing in total to some 35 TWh of energy savings per year (2010) and corresponding to some 3 MTOE of primary energy and some 14 Mt of CO2 by 2020 (European Commission 2008). The rest of the saving is composed mainly of technological development and MEPS.

Furthermore, for single product groups the potential savings were calculated. For example: for the new label on televisions, it is estimated that a total energy savings potential of 46 TWh by 2020 could be realised. Out of this total potential, it is further estimated that energy labelling could catch about 12 TWh (about 1 MTOE) by 2020, corresponding to emission reductions of 4,8 Mt of CO2. As to lighting, the Ecodesign preparatory studies indicate that general lighting appliances would provide some 75 TWh of savings potential, of which energy labelling could catch some 16 TWh (about 1,5 MTOE) by 2020, corresponding to reduced emissions of 6,4 Mt of CO2 (European Commission 2008).

It is estimated that with an extended product range, the energy label could lead to savings of some 22 MTOE per year by 2020, corresponding to annual emission reductions of about 65 Mt of CO2. More than half of these savings would come from the heating and water heating appliance alone, which have not yet been addressed by the labelling directive. The rest of the savings would come from the upgrading of the existing eight measures and from a new measure on televisions (European Commission 2008).

With full implementation of the current labelling scope plus coverage of all energy-related products, the directive could lead to additional savings of some 27 MTOE by 2020, i.e. 5 MTOE additional savings by broadening the scope to include windows, commercial refrigeration and heating appliances.

The European Union’s mandatory labelling of electric appliances has been an attempt at changing behaviour of consumers as well as of producers/importers, and it has been a definite success in the European consumer market. It is estimated that energy labelling has contributed to annual energy savings in order of 3 MTOE corresponding to emission reductions of some 14 Mt of CO2 over the period 1996-2004 (European Commission 2008).

Furthermore the combined effect of the labelling scheme and the minimum energy efficiency requirements have already led to significant energy savings for single product groups. For example in 1995, refrigerators consumed on average 425 kWh/year. In 2005, they consumed approximately 292 kWh/year, which represents a reduction of about 30% (Ecodesign Preparatory Study Task 2).

There have been a number of studies of the impact of the labelling directive. These track the increased take up of higher efficiency appliances over the past decade. Of all the appliances covered by implementation directives, the impact has been greatest for white goods, particularly refrigerators, freezers and washing machines. The majority of these products sold today carry an A or B rated label or better (i.e. A+ or A++) compared with the majority of products sold in 1994 carrying a D rated label or worse. Recent market data on the share of energy efficient appliances suggests that the EU market for refrigerators is moving towards a higher share of most efficient classes of appliances. The next figure gives an overview of the market development.

The success of the labelling scheme is also demonstrated in the high number of third countries that have adopted a similar label or sometimes an exact copy of the EU energy label.

It is unknown, which share of the overall technical and economic potential has been achieved by energy labelling. However, the European Commission (2008) has estimated that energy labelling schemes and consumer education about them with all covered products could account for about half of the increased take up of more energy efficient appliances due to policy.

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy