The programme aims to help low-income households save money and reduce energy consumption by replacing old, inefficient refrigerators at no cost to them. It also recycles the old model. During 2008-2010, 45 electricity distribution companies participated in the programme, replacing more than 380,000 refrigerators to save almost 190,000 MWh/year and reduce peak demand by more than 23,000 kW.

To change this situation and to replace these old refrigerators the programmes donate new energy-efficient refrigerators (class A) to low-income consumers. It is financed by a charge collected from all electricity consumers. The obligation to invest in demand side energy efficiency programmes began in 1998 and is regulated by ANEEL, the national regulatory agency. Distribution companies decided which programmes to carry out. In 2011 this obligation became a national law (instead of a regulation by ANEEL).

The initial cost for the utilities (distribution and supply energy companies) is high as the refrigerators are free to the customers, but 26 out of 94 programmes achieved direct economic benefits higher than the costs. The others at least achieved social and environmental benefits. One aim is to reduce the utilities’ commercial losses due to irregular connections. The programme also wants to aid the provision of energy in the long term for all households in Brazil by reducing the overall consumption.

Brazil has introduced several programmes to increase the energy-efficiency of appliances. One of these programmes is a refrigerator replacement programme. Electricity distribution companies are required to invest part of their revenues in energy efficiency programmes. Since 1998 these funds were often used by the distribution companies to invest in energy-efficiency programmes to support low-income households. Frequently used programmes were refrigerator replacement programmes.

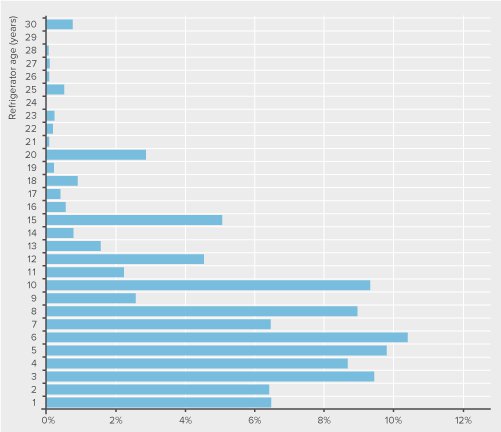

Around 30% of the Brazilian refrigerators are more than 10 years old. Most of these old refrigerators belong to low-income households. The following figure illustrates the age of the refrigerators in Brazil (in 2007).

Several policies especially in countries of the European Union have been established to replace old refrigerators with new, more efficient ones. However, most of these policies only partly fund the purchase making the replacement less attractive for low-income households. For example, under Belgium’s Subsidy Schemes for Energy Efficiency Measures 25% of cost and up to maximum of EUR 150 are provided for a new refrigerator. As opposed to this Brazil’s programme is tailored to increase energy efficiency among low-income groups by bearing all of the costs (for the new refrigerator and for the recycling of the old one) (IEA database).

Refrigerators represent 70% of total low-income households’ electricity consumption. There is a social tariff for low-income households for electricity supply, which on average covers 65 kWh per month per household. Utilities have to invest 0.5% of net sales in efficiency programmes, which equals R$ 300 million. This compares to R$ 1,4 billion annually to subsidize low-income electricity tariffs (as of 2007) (Jannuzzi 2007).

None of the most popular refrigerators in the stock (in 2005) were labelled ‘A’ or most energy efficient (Jannuzzi 2007). And refrigerators found in low-income households are usually the oldest ones.

The obligation and public benefits funds scheme aims to help low-income households save money and energy by funding energy efficiency measures, such as through a refrigerator replacement programme.

Each utility carries out and manages its own energy efficiency programme within its concession area under the supervision of the national regulator. Therefore it is a national, local and regional policy depending on the focus of each utility.

The new refrigerators must be labelled as “A”, have the PROCEL Seal and each utility’s programme must achieve a cost-benefit ratio (CBR) less than 0,8 (i.e., costs are no more than 80% of the economic benefits and the programme achieves a net economic benefit). The regulator will approve programmes with higher CBR only if their social and environmental benefits are worthwhile. The utility must report programme expenditure and the ex-post results (saved energy, refrigerators installed).

The replacement programme interacts with a refrigerator recycling programme (SENA) and the social tariff on electricity. The interactions could be improved (see: possible further improvements).The programme also benefits from the Brazilian energy label for appliances. The regulator requires that the refrigerator models in the programme are labelled as A.

The interaction of these different programmes is a quasi-planned interaction. The Brazilian Congress enacted new rulings for the application of the social tariff and for low-income energy efficiency programmes without discussions with other players, such as utilities.

The replacement of the refrigerators is combined with a recycling programme and aimed specifically at low-income households. And the programme is subjected to measurement and verification (M&V).

To optimise the policy package, more integrated discussion and planning are necessary to ensure the main actors are working towards the same goals. It would be beneficial to envisage a strategy for phasing out the subsidies for the social tariff. So far, the low-income households not only get the benefits from a new and more efficient refrigerator but also continue to have a subsidised tariff. Brazil would probably be better off by removing this type of subsidies, and these programmes could provide a way out without severe impacts on electricity bills – households save many kWh and pay more for each kWh.

Pre-conditions are test-procedures, an agency, a funding scheme and some additional conditions.

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

No state agencies are needed to implement the programme as this task is mandated to the utilities. An agency is needed to oversee the programmes. This task is assigned to the energy regulator ANEEL.

Funding

The programmes would not be possible without the ‘wires charge’ that is used to fund them.

The social tariff for low-income households is part of the funding scheme. Only low-income consumers that participate in the Brazilian income transfer programme called “Bolsa Família” are eligible to get the electricity social tariff and, therefore, participate in the regulated energy efficiency programmes.

So far, there have been no discussions on decoupling revenues from the amount of power supplied or changing regulations to allow direct cost-recovery mechanisms from these energy efficiency programmes. The programmes are fully financed by electricity consumers and the refrigerators are free to low-income households.

Test procedures

Not directly for this programme, but as a basis for the energy label, which is needed for selecting the replacement refrigerators

ANEEL publishes the Manual for the Energy Efficiency Program containing rules and guidelines for utilities to submit their programmes to the regulator. This most recent Manual dates from 2008. It specifies several steps of implementation by the utilities: pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, execution, verification, fiscal and financial audit, final report, M&V validation and evaluation. ANEEL then oversees programme implementation.

Co-operation of countries:

There is no co-operation with other countries so far.

Quantified target:

The policy has no quantified target. Targets are set by utilities under their own criteria.

Actors responsible for design

Utilities design, manage and implement the programmes. Forty three utilities are currently (2011) carrying out refrigerator replacement programmes.

Actors responsible for implementation

Utilities (LIGHT, COELBA, ESCELSA, CELPE, AMPLA, CEMIG etc.)

Monitoring

A monitoring system is in place, run by utilities. The utilities’ programmes will be inspected by ANEEL to ensure that utilities have their own tracking system.

Accounting, fiscal and energy data are recorded.

Evaluation

An ex-post impact evaluation exists for some of the programmes. Results are not disclosed, but some can be provided without identifying the utility. Refrigerator replacement achieved energy savings of 81% for refrigeration in a case study in the Northeast region. Preliminary data in two other case studies show a reduction in refrigerator energy consumption of 75% and 70%.

Economic benefits and costs have been evaluated through the cost-benefit ratio (CBR) from the distributor perspective. At the end of the programme, the CBR is recalculated with actual figures.

Co-benefits

Consumers frequently claim the energy efficient refrigerators are too small. The acceptance rate could be higher if the refrigerators were bigger without unacceptably compromising the cost-benefit ratio.

The programme has not been able to eliminate illegal connections and power theft.

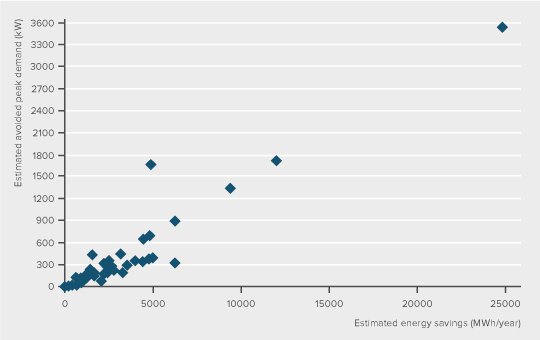

Please refer to the next figure. It presents the estimated energy savings and peak demand reduction, based on ANEEL data covering energy savings, peak demand reduction, CBR for all utilities by sector (residential, industrial, commercial, services etc), end use (refrigeration, lighting etc), utility.

45 utilities were carrying out refrigerator replacement programmes, totalling 383,760 appliances from 2008 to 2010 that would save 186,294 MWh/year and reduce peak demand by 23,277 kW.

The target years for these estimated savings were 2008-2010

The energy savings from refrigerator replacement achieved 81% reduction in refrigerator electricity consumption in a case study sited in Northeast region. Preliminary data from two case studies in the Southeast region show a reduction of 75% and 70%.

Energy saved in total electricity consumption for low-income households: Average total monthly consumption among a sample of customers of one utility fell from 167 kWh to 94 kWh after the replacement programme (a reduction of 44%). (Jannuzzi, 2007).

For this study, a statistical sample of refrigerators had their electricity consumption measured both ex-ante and ex-post. The average consumption and then energy savings were computed and extrapolated to the neighbourhood.

The evaluation years were 2009 and 2010.

This result suggests that each household saved almost 900 kWh per year of electricity from the refrigerator replacement.

No information is available but the number of low-income households eligible for a free refrigerator is probably much larger than the 383,760 appliances distributed from 2008 to 2010 would suggest, so there is probably room for extending these programmes.

The new refrigerator is supposed to save at least the same amount of electricity as the difference between the subsidised tariff and the residential one → 53% (Jannuzzi 2007).

Values of the utilities’ ex-ante estimates for the CBR reported by ANEEL vary significantly from unrealistic lower and upper limits (from 0,04 to 272,15). Out of 94 programmes, 56 are between 0,7 and 2,0, which is a more realistic range. (If the CBR is below 1, the programme will have a net benefit, i.e. the benefit is higher than the costs.)

There will always be a net benefit for the low-income customers participating, since they will save energy and costs for no initial investment.

Only 26 of the 94 programmes have an expected CBR under 1.0; i.e., these are cost-effective. The rest are not cost-effective, but potentially have social and environment benefits.

The regulator will have ex-post evaluations from all distributors and will be able to evaluate those programmes. These are not yet available but expected soon.

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy