The French network of local energy information centres (Espaces Info Energie, hereinafter referred to as EIE) provides individualised advice on energy efficiency in buildings to the public, primarily to the residential sector. In France the lack of sufficient information on this topic is considered to be one of the major obstacles to decreasing energy use in buildings. This barrier is addressed by the EIE network, which consists of about 250 offices throughout the country. In 2009, the people who received the energy advice made investments of €465 million and saved 98,740 toe of energy and 166,620 tonnes of CO2 emissions per year.

In 2000, the French government assigned ADEME, the French Environment and Energy Management Agency, with the task of creating an energy advisory infrastructure. Launched one year later, the EIE network has since been implemented in many communities throughout the country. In 2011, there were around 250 offices offering individual energy advice at the local level (ADEME 2011).

Since 2001, the EIE’s task has been to provide the public with information on energy efficiency in buildings.

The individual EIE offices have two tasks: First, they provide individual end-users (households, small companies, organisations) with free, independent, and customized advice. Second, they perform outreach activities to raise awareness for energy efficiency in buildings in the general public. Thus, the network complements and reinforces other policies or measures that aim to increase building energy efficiency by making these policies known to the public.

ADEME oversees, monitors and evaluates the work of the EIE offices. It does so with the help of its 26 regional branch offices, which each employ a regional co-ordinator. In addition, a Strategic Committee, comprising national, regional and local government officials, determines “the actions that help consolidate and develop the EIE network” (ADEME 2010).

ADEME funds the network substantially (€10.5 million per year, Chédin 2010). These funds are used directly for the energy advisors’ salaries and indirectly for producing media campaigns and information materials as well as for conducting training courses to keep advisors informed with the latest developments. Local or regional authorities provide additional funds.

Although there have never been targets set, the network as a whole has achieved successes continuously. For example, aggregated data shows that in 2002, 42,864 toe of energy and 72,333 tonnes of CO2 per year were saved. Seven years later, in 2009, the EIE network was estimated to have saved 98,740 toe of energy and 166,620 tonnes of CO2 per year (Chédin 2010, p. 10).

In Europe especially, there are several countries that have established a local energy information network, such as the Czech Republic, Estonia or Germany. Unlike the French service, German energy consultation provided through consumer information centres is not for free (Mure & Fraunhofer ISI 2011, p. 1). In 2009, the Finnish government also started to implement a local network of energy information centres with the goal of providing “the consumers with high quality and reliable energy advice” (Laitila 2010, p. 2).

In the United Kingdom, the Energy Saving Trust has a similar network of around 50 local advice centres, with a staff of over 500. The network has advised 5.8 million customers since 1996. In Sweden, municipalities are obliged to employ at least one local energy advisor to provide objective advice to households and small businesses. (UNDP 2009, p. 34)

According to the World Bank, France’s energy use per capita rose from 4,045 kilograms of oil equivalent (kgoe) in 1997 to 4,254 kgoe in 2001 leading to an overall consumption of 260,322.0 ktoe (compared to 250,017.0 ktoe in 1997) (World Bank). In 2000, rising oil prices intensified the situation.

Against this backdrop the French government launched the National Programme for the Improvement of Energy Efficiency, which included the creation of the EIE network.

In 2011, ADEME estimated that there are approx. “30 million residences and over 814 million m2 of heated commercial buildings” in France. Annually, 300,000 new residential buildings and 14 million m2 of heated commercial buildings are added (ADEME 2011).

The EIE network was launched at a time when France had been experiencing rising energy prices and increasing energy use (per capita). It had become a vital policy task to reduce energy use and to decrease CO2 emissions. Chédin describes the network as an important “pillar of the French climate change policy” (Chédin 2010, p. 3).

More specifically, it aims at providing the public with information on why and how to improve energy efficiency in buildings. ADEME states that the building sector, consuming 70 million toe annually, is the “biggest consumer of energy across all sectors of the [French] economy. […] [T]his represents […] 1.1 tonnes of oil equivalent consumed every year by every French citizen. This energy consumption produces 120 million tonnes of CO2 emissions, representing 25% of France’s national emissions.” The government is committed to cutting all these figures by 75% before 2050 at the latest (ADEME 2011).

The EIE network has two major tools to make people aware of, and motivate them to act on, energy efficiency in buildings. First, free, individualised information can be obtained in the EIE offices, via telephone or email, summarized as “individualised energy advice.” Second, “outreach actions” (e.g. fairs, school events, workshops, visits to demonstration buildings) also aim at raising awareness for the topic of energy efficiency (Chédin 2010, p. 1).

It is important to note that the information service also works on a complementary basis, and thus aims to reinforce, other policies, in that it provides information about those other policies, e.g. zero-interest loans or tax incentives for energy saving investments.

In 2001, the national energy agency ADEME launched the EIE network on the basis of the Programme National d'Amélioration de l'Efficacité Energétique (PNAEE) or: National Programme for the Improvement of Energy Efficiency.

The governance structure is two-tiered. First, there is the Strategic Committee whose decisions affect the whole network. The Committee consists of representatives from the Association of French Mayors, the Association of French Regions, the Association of French Départements as well as from the Assembly of French Communities and is chaired by ADEME (ADEME 2010).

On the second level, the network is split into 26 regional divisions. Each of ADEME’s 26 regional branch offices employs an EIE officer who co-ordinates the networks operations in the specific region.

In the end, the EIE’s actual work is delivered through local host organisations.

The sectoral focus are the residential and commercial (SMEs) sectors.

However, a 2003 evaluation found that 73% of the EIE’s clients had been homeowners (MURE 2012, p. 1) making the residential sector the centre of the EIE’s attention.

The policy focuses on buildings. In principle, all active building technologies as well as passive options (mainly thermal insulation) and changes in user behaviour are targeted.

The free, customised energy information service EIE creates incentives to invest in energy efficient building measures and/ or to change consumer habits. It does so by way of lowering the search costs for clients to find adequate products or measures and reducing uncertainties about both the technical performance and the costs and benefits (i.e. achievable energy savings, plus co-benefits) of energy efficiency improvements. As the EIE advisors also inform people about available financial assistance (e.g. grants, loans), the policy indirectly helps alleviate financial constraints too.

Starting very early in the 1970s, France introduced its first energy efficiency measures in order to reduce pressures from rising oil prices and decrease energy dependency. Since 1973 the French government has gradually tightened the minimum energy performance standard for buildings, which is called "Thermal Regulation" (RT). The 2012 RT stipulates a minimum energy performance of below 50kWh/m2 per year for all buildings whose application is submitted after January 13, 2013 (Mure 2011, p. 1). Concrete information regarding minimum energy performance standards and building labels, that increase the value of a building, can be accessed via information centres. Particularly promising is the fact that France’s Building Plan, developed by Grenelle Environment Forums, is “projecting 400,000 building renovations per year from 2013” as this is likely to drive the demand for energy efficiency consultation within the general public (Electrical Efficiency Magazine 2011).

Similarly, this holds true for France's mandatory building energy performance certification (EPC) scheme, the Energy Performance Diagnosis, which was introduced following EU legislation (Energy Performance of Buildings Directive). The EPCs visualise both, a building's energy consumption as well as greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, they give recommendations on which effective energy saving measures to take (Mure 2011a, p.1). Information centres can give general information about the rating (e.g. the expenses for a certificate, or where to find a qualified expert to have the building rated) or answer questions revolving around the implementation of the given recommendations.

The French government has introduced various financial support instruments for buildings exceeding the building regulation and for investments in energy efficient building renovation for investments in renewable energy sources and other energy efficiency investments as well as general energy audits (Roger et al. 2010, p.8). For a general overview of funding opportunities and consultation on how to apply for funding, energy information centres offer a good starting point for the public.

As ADEME also launches media campaigns on energy saving issues, which are to raise the public’s attention on the topic, local information centres play a crucial role if citizens wish to receive more in-depth information. The "why wait" campaign (French: pourquoi attender) even refers directly to the significance of the information centre network (Mure 2008, p. 1).

Moreover, France has initiated a comprehensive capacity building programme for the construction industry. The programme, called “Training for Sustainable Building Plan (French: Plan de formation bâtiment), mainly consists of three pillars. First, ADEME in close co-operation with regional authorities and local actors of the construction sector (e.g. architects) promote the establishment of Resources Centres for Environmental Quality of Built Environment. Actors from the building industry or public services can access information about best practice green buildings or about business partners (Mure 2010, p. 1). Furthermore, plans also involve establishing regional institutions that co-ordinate and promote “education and lifelong training in the building industry” (Mure 2010, p. 1). This measure will disseminate information about new technological and policy developments to craftsmen, engineers and architects etc. more quickly. This makes sure that legislative orders or technological advancements are implemented without further delay. Thirdly, ADEME together with other actors have started to design a training programme for building and installation workers and contactors, for example to increase the “general knowledge about building and climate change” or “how to use actual efficient solutions in refurbishing buildings” (Mure 2010, p. 1).

Last but not least, France introduced so called Energy Saving Certificates (ESCs) in 2005. As the mechanism was regarded as a success for the period 2006 to 2009, is has been continued for another three years (2011 to 2013). Putting it in a nutshell, legislation has made it mandatory to energy suppliers to decrease energy consumption and to achieve energy savings by supporting energy consumers to save energy. While specific targets have been stipulated, law does not define how to reach these goals. However, reducing energy consumption in existing buildings was regarded as a priority (ADEME 2011a, p.4). Since 2008, “actions to train construction sector professionals in energy saving” have been implemented meaning that certificates have been issued in response to such actions (Mure 2011b, p. 3). ESCs are issued as soon as targets are met. Non-compliance will be fined (ADEME 2012).

The dissemination of information on the afore-mentioned topics is planned. The EIE network functions as an interface between the supply side of energy efficiency measures (e.g. technology producers, regulators) and the demand side, i.e. the French public. The network functions as a communication tool for, and thus complementary to, other policies that affect energy efficiency in buildings directly or indirectly.

Energy advisors working in EIE offices are constantly trained by ADEME’s workshops/ training courses. This ensures that the advisors are up-to-date with current (policy and or technological) developments. Moreover, ADEME conducts national media campaigns and develops information material on energy efficiency.

Thus, the framing of national policy rests within the authority of the national agency. However, subnational actors are represented in a Strategic Committee on the national level and “define the actions that help consolidate and develop the EIE network” (ADEME 2010). They can influence the policy of the network. Subnational actors also have a say in the regional operation of the network.

As EIE offices work at the city or community level, they are aware of local peculiarities.

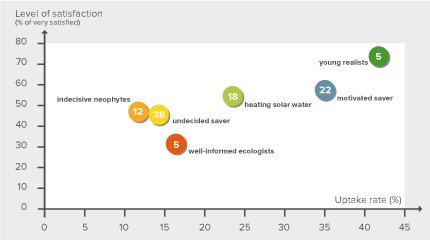

Nearly 80% of the clients have been satisfied with the network’s efforts (see the figure below). In addition to that, the share of those advised and, afterwards, taking action increased from 26% to 56% (Chédin 2010, p.10 and the next table) between 2003 and 2009. Consequently, improvements regarding the service currently offered by the EIEs do not seem to be necessary upon first sight.

| Measure concerning... | Individualized advice | Markets and fairs | Workshops and conferences |

| Heating system | 46% | 28% | 21% |

| Solar hot water | 25% | 32% | 33% |

| Thermal insulation | 19% | 4% | 8% |

| PV system installation | 1% | 5% | 33% |

Source: Chédin 2010, p. 8

The downside is, that only 13% of the French public know about the EIE. Presumably, if more people knew about the EIE, more energy could be saved. However, as the network is already overburdened, funds would have to be increased. Otherwise, the satisfaction rate of those being advised could fall.

A service charge could solve the problem of funding. But probably the number of clients would decline as a consequence.

Due to their limited capacities, energy experts at EIEs cannot conduct on-site visits at clients’ homes. However, evaluations have shown that such on-site visits lead to more reliable and adequate energy efficiency recommendations and advisory statements and, thus, increase the chance that recommendations are actually implemented. In Germany, for instance, subsidised energy audits are available through local consumer information centres as well as through independent energy advisers working as freelancers. State-subsidised service costs for such an on-site visit is levied at €45. As the EIE network is heavily decentralised, such expansion of service could first be tested in some selected municipalities, and then be extended nationwide, IF the idea falls on fertile ground – and IF funding allows.

Another expansion of the service provided could be to offer assistance to investors during design and construction or retrofit. Such assistance could range from advice in soliciting offers from and selecting the best designers and construction and installation contractors to assistance in quality control. It could significantly reduce transaction cost and perceived risk for investments in energy efficiency.

Finally, the Behave Project (2010) states, that “[w]hereas several regions and cities actively support the local EIEs, still many of them have not taken too much interest in this initiative and provide little or no funding” (Behave Project NA, p.2). The lack of funding from some subnational authorities contradicts with one of ADEME’s “priority actions”, one of which is “[k]eeping the public informed via its Espaces Info Energie (Energy Info Points)” (ADEME 2011). As the residential building sector consumes large quantities of energy, some subnational governments miss a chance to contribute to national emission reduction goals by providing insufficient resources to EIEs. A nationwide competition, awarding best performing municipalities or regions in terms of energy savings, might substantiate the significance of the EIEs within each region and generate support from their respective subnational authorities.

Moreover, the package can be optimised, as well.

There are several measures on how to improve France’s policy package to increase energy efficiency in buildings. However, one must be aware of the fact that filling gaps in the package through measures that drive the public’s demand for energy consultation in EIEs might overburden some offices. If measures affect the demand for consultation, sufficient resources must be made available. Otherwise, the satisfaction rate of EIE’s clients might decrease rapidly.

A programme supporting energy-efficient demonstration buildings and energy-efficient renovations in each region could provide the EIEs and the training of suppliers with convincing evidence of the feasibility and benefits of energy-efficient solutions. While EIE offices execute on-site visits to demonstration buildings, a study found that an overwhelming majority of over 75% of those visits are related to energy production. Only close to 15% were energy efficiency-related (Métreau & Tillerson 2007, p. 560).

For example, France could introduce electricity bills which suggest potential energy efficiency improvements. Unlike recommendations given in the energy performance certificate, the whole population would receive such advice, thus raising broad awareness on the topic.

There is no regulation stipulating the replacement of old boilers (above a certain age). As these are heavy energy consumers, a policy measure incentivising or requiring to exchange old boilers for a new one could contribute significantly to France’s climate policy goals.

France has profited from the fact that its energy agency ADEME, which manages the network, has regional branch offices. Thus, national co-ordination efforts are easier as regional offices are aware of policy peculiarities and developments on the regional level. Especially, since regional as well as municipal actors have a say in determining the direction of the network through the strategic committee.

As EIE offices have been located in existing host organisations such as non-profit environmental, housing or consumer organisations, or in local administrations, ADEME has a) circumvented expenses for establishing their own offices and b) benefited from expertise and network structures of those existing host organisations.

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

ADEME, the French Environmental and Energy Management Agency, manages the network.

Funding

ADEME processes funding for the individual offices to support every advisor position. Local and regional authorities may provide additional funding.

According to MURE (2012), the network is funded to one third by ADEME, while the other funds come from local and regional authorities. Note that running costs of host organisations are not covered.

For example, the EIE in Marseille is funded by ADEME, by the City of Marseille, by the Provence Alpes Côte d'Azur Regional Council (a French administrative region in south-east France), by the Marseille Provence Metropole Urban Authority and, last but not least, by the Bouches-du-Rhône Departmental Council (Geres).

In 2000, ADEME was assigned with the task of implementing a local energy information service. Since its launch in 2001, the programme has been administered by ADEME. However, the Strategic Committee “define[s] the actions that help consolidate and develop the EIE network” (ADEME 2010).

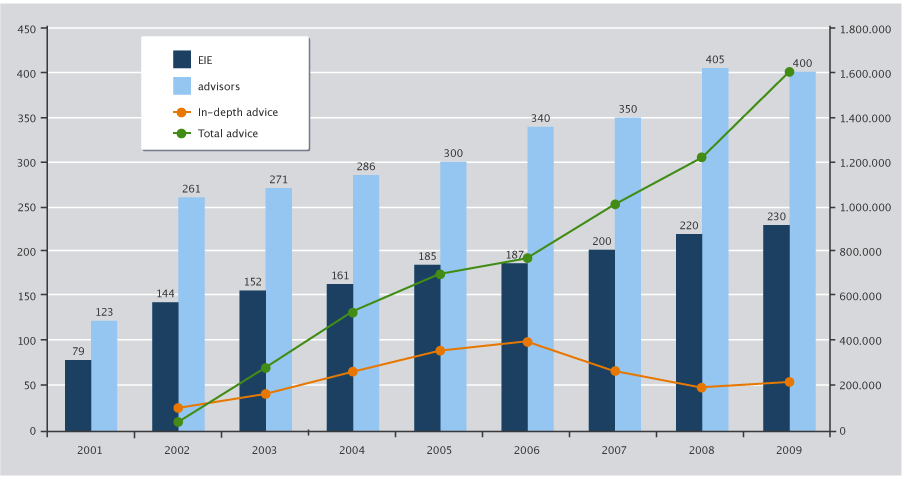

The programme was introduced in 79 communities. From then on, the network expanded gradually consisting of around 250 offices in 2012.

The EIEs are located within host organisations, such as non-profit environmental and renewable energy organisations (43%), non-profit housing organisations (35%), local authorities (15%), non-profit consumer organisations (7%). “To become, and remain, an EIE, the host organization has to provide free individualized advice to the public, develop a local outreach programme by participating in markets and fairs and other local awareness-raising activities, and report on its activities to ADEME on an annual basis” (Chédin 2010, p. 2).

ADEME also created a mechanism for monitoring the EIEs’ activities and evaluates the impacts of the programme regularly (see Monitoring and Evaluation).

The EIE is a complementary measure to other policies and technological developments. As it is a pure information service, it can be regarded as an interface between the energy efficiency supply side and the demand side (i.e. the home-owners and investors).

As ADEME is responsible for keeping advisors up-to-date with respective developments, clients get information about (present and even future) best available technologies, cost-effective technologies and funding opportunities. By delivering this customised and free information, people’s uncertainties are minimised and they become inclined to invest in energy efficiency measures or to change their habits towards a more energy-efficient behaviour.

Apart from the individualised advice, EIEs organize local events to proactively get in touch with the public.

Co-operation of countries

France is currently attempting to export its EIE design to Poland, Romania and Tunisia. “Further afield, the creation of an EIE network is also being considered in Russia under a partnership between ADEME and the new Russian Energy Agency” (Ademe 2010).

Actors responsible for design

France’s national government announced the programme and assigned ADEME with designing it.

Actors responsible for implementation

The national energy agency, ADEME, manages, monitors and evaluates EIE’s overall work. Its task also includes the publication and distribution of materials as well as the training of the advisors.

The Strategic Committee that consists of regional and local representatives determines the direction of the network.

ADEME’s 26 regional branch offices co-ordinate the EIE’s work on the regional level.

Sustainability aspects

By having 250 offices across France the idea of energy-efficiency and, thus, sustainability is “visible”.

Co-benefits

Those 250 offices employ 400 energy advisors, i.e. job creation is an important co-benefit.

Some local authorities do not seem to be quite so supportive to facilitating the work of the EIE network (Chédin 2010, p. 2)

In 2003, ADEME evaluated the network for the first time. Apart from some findings regarding EIE target group and actions undertaken by clients, the evaluation found that a sample of 68 actions undertaken led to 40.73 toe/year of energy savings.

Six regional evaluations carried out in 2006 calculated energy savings and CO2 emission reductions per in-depth interview. The partners in such a customized interview (20 minutes) had taken actions that would lead on average to an annual saving of non-renewable primary energy of 0.31 toe/year and a CO2 emissions reduction of 0.58t CO2eq/year (Mure 2012, p.2).

Between 2006 and 2010, 17 of the 22 regional EIE networks, including the above mentioned six regional assessments, evaluated their “individualised energy advice” service. Unfortunately, data on three evaluations carried out in 2010 was not available and only eleven networks carried out an “environmental impact evaluation”, the basis for the numbers shown further below. As regions used the same questionnaires, ADEME was in the position to compile the data (MURE 2012, p. 3).

Based on Dialogie (the EIE’s computer programme to record data gained through individual consultations) the networks, first, broadly defined what was possible to establish. Second, a questionnaire with ten questions was developed to find differences before and after clients undertook action in response to consultation. Questions revolved around “type of advice, energy, size of dwelling, number of inhabitants” (Chédin 2010, p. 9).

The environmental impact was calculated as follows (Chédin 2010, p. 9):

[Amount of In-depth Advice] * [Uptake Rate] * [Contribution Rate] * [Average Energy Saving Unit of Work]

Uptake Rate: “number of people who carried out an investment (heavy work/installations) and the amount of in-depth advice”,

Contribution Rate: “number of people who declared that the advice had contributed a little or a lot to the realization of their work compared to the number of people who completed work”,

Average Energy Saving Unit of Work: “calculated based on the work actually completed. This economy can be calculated in energy (Mtoe) or emissions of equivalent CO2”.

Calculation on the environmental impact and other results was “a simple addition of the data and not a meta-evaluation. The sum of the fourteen evaluations carried out between 2006 and 2009 represent a sample of 55,000 beneficiaries“ (Chédin 2010, p.10).

For the period 2006 to 2009 the energy savings and CO2 savings are (Chédin 2010, p. 10):

Year Energy saved in toe/year – CO2 saved in tonnes/year

from advice in 2006: 66014 toe/year – 111389 t CO2/year

from advice in 2007: 73539 toe/year – 124097 t CO2/year

from advice in 2008: 81923 toe/year – 138244 t CO2/year

from advice in 2009: 98740 toe/year – 166620 t CO2/year

Example:

In 2009, EIE offices gave about 220,000 in-depth advice. 51% of the clients carried out a heavy work/ installation investment, of which 56% had moved into action due to EIE consultation and 2.7 tonnes in CO2 emissions was saved. The latter figure is based on findings that 6234 tonnes in CO2 were saved due to 2413 works carried out (6234/2413 ≈ 2.7). Consequently:

220,000 * 51% * 56% * 2.7 ≈ 166,620 tonnes CO2/year

(Mure 2012).

The uptake rate (those who took action after having been advised) increased from 26% in 2003 to 56 % in 2009.

Literature tends not agree with regard to the amount of funding. MURE (2012) estimates overall funding to be at €15 million, of which €5 million was provided by ADEME. According to the IEA (2009) €8.5 million was given to the network by the agency. Then again, Chédin (2010) talks about €10.5 million in 2010.

A 2003 evaluation found that the average investment costs were at €7,650 per action.

In 2010, this figure had increased to €8,386. The highest investments are the ones for the photovoltaic systems (€16,000 on average), solar systems for hot water and heating (€14,000), exchange of heating systems (€11,700) and insulation (€10,700)” (Mure 2012, p. 3).

In 2008, €465 million of investments were initiated by the EIE network

There is no information available on what kind of energies were saved due to the network. However, overall energy savings of 81,923 toe in 2008 can only be regarded as quite impressive against the backdrop of €15 million which is invested annually into the network. But one must keep in mind that savings resulted not only due to investments in energy efficiency measures, but also through investments in renewable energy technologies.

In 2008, France invested about €15 million into the EIE network saving 81,923 toe and boosting investments of €465 million in that same year.

In other words this means that for every Euro spent on the network, France reduced a) its energy consumption by 0.0055 toe and b) was able to push investments to €31.

Further information:

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy