Starting as early as 1974, Barbados has managed to develop a solar water heating industry and the use of solar water heaters in about 40 percent of all its households today. This is around 70 percent of the households that have water heating at all. A combination of fiscal incentives enabled this success: (1) import tariffs were eliminated on the raw materials used to manufacture solar water heaters; (2) a consumption tax of up to 60 % was imposed on all electrical and gas water heaters; (3) homeowner tax incentives for solar water heaters of up to BBD 3500 (approx. €1400).

The simple payback period for homeowners and hotels is less than two years when replacing electric water heating. Cumulative energy cost savings to building owners had already exceeded tax incentives by a factor of 12 in 2003. Oil cost savings to the national economy were already higher than the cost of the solar water heaters by then, with further savings to be expected over the useful life of the water heaters.

In 2008, Barbados accounted for 75% of the solar water heaters use in the Caribbean and the country currently manufactures more than 80% of the solar water heaters demand in the region (UNEP 2012).

Governmental economic incentives have been created to lower the costs of Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs), to create a market for alternative energy, and for the capture of societal benefits such as reducing environmental emissions and oil imports. As early as in 1974, the Government of Barbados (GOB) enacted its first Fiscal Incentives Act. Through the Act, import tariffs were eliminated on the raw materials used to manufacture solar water heaters while a consumption tax of up to 60 % was imposed on all electrical and gas water heaters. During the period from 1980 to 1992 the GOB implemented a Homeowner Tax Benefit that allowed homeowners to claim the full costs of solar water heaters up to BBD 3500 (approx. €1400) on their income taxes. The homeowner tax incentives were eliminated in 1993 because of structural adjustment difficulties caused by economic recession (Perlack & Hinds 2003 p. 11). In 1996, incentives were re-introduced and homeowners were allowed to deduct a maximum of BBD 3500 (approx. €1400) from their income tax for expenses on repairs, renovation, energy or water saving devices, solar water heater and water storage tanks. Under the 2008 modified Income Tax Allowance US$5000 was allotted per year for Home Improvement. Out of $5000 up to $1000 can be used for energy audits and under the Energy Conservation and Renewable Deduction, homeowners can claim a reduction of 50 percent of the cost of retrofitting a residence or installing a system to produce electricity from a source other than fossil fuels (UNEP, 2012). The Barbados Training Board has established opportunities for local skill enhancement for the prospective Solar Water Heater Technicians.

The policy is very cost effective. Cumulative SWHs energy savings (65 million kWh annually with rate payers value of at least $BD 23 million – €9 million approx. – or a cumulative $BD 267 million – €110 million approx. – through 2002) substantially exceed the tax costs of the incentives ($BD 21.5 million through 2002) – €8 million approx. At income tax rates averaging around 30 %, the cost to the investors of water heaters may have been around €25 million. Oil cost savings to the national economy were estimated to be at least $BD 6 million in 2002, so their cumulative value through 2002 was already higher than the cost of the solar water heaters by then, with further savings to be expected over the useful life of the water heaters. Simple payback time to homeowners and hotels is less than two years when replacing electric water heating (Perlack and Hinds, 2003; partly own calculations based on this source).

Other success stories for the promotion of SWH can be found in countries such as Tunisia, Israel and Cyprus.

The Prosol programme of Tunisia addressed the competitiveness concerns of solar water heating technology by making their prices competitive with conventional water heating. The water heating market was distorted by the subsidies on fossil fuel-based water heating alternatives. Launched in 2005, Prosol is a multi-prong programme that involves a variety of instruments to correct distortions in the market for water heating. It includes a 20 % subsidy on the capital cost of SWH, low interest loans (households contracting loans were charged at 0% interest rate in the first twelve months and 4% in the subsequent six months, risk-adjustment for private lenders by setting up a system of guarantees and raising awareness of the financers and suppliers regarding the added value of green investments, which led to improving the quality of products offered (Trabacchi C. et al., 2012). Read more in the bigEE good practice policy example on Prosol.

In the case of Israel, it was the first country to introduce legislation in 1980, making the use of solar energy in new buildings compulsory for the reasons of energy security . The legislation induced a market shift in the favour of SWH use in buildings, and currently 85 % of Israel’s 1,650,000 households use SWH (GEF, 2012).

Similar to those in Tunisia, Cyprus also used financial incentives to encourage residential, commercial and non-commercial users to install SWHs. The amount of subsidies on investment costs varies according to different applications: 20% for domestic solar hot water systems; 45 % for solar systems for swimming pools; and 55 % for solar systems used for space heating and/or cooling. Thanks to these incentives currently 90 % of households and 53 % of hotels in Cyprus have installed SWH (EuroObserver’Er, 2013).

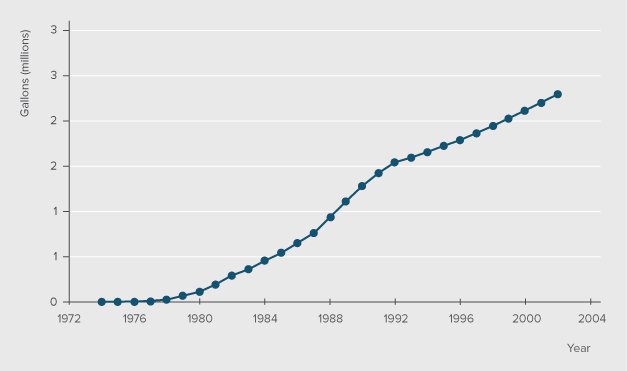

There were only a very limited number of solar water heating units installed in Barbados in 1974. After the enactment of the Fiscal Incentives Act this number started to rise gradually. In 1979 there were about 1000 units installed nationwide. In 2009, a total of approximately 45000 water heating systems were operating in Barbados (about two out of five households (Schwerin A. 2010, p. 34), or about 70 percent of those having water heating at all).

It is a national policy.

Through the exemption of import tariffs and by giving fiscal incentives to consumers on the installation of SWH systems the government of Barbados (GOB) aimed to create a market for solar water heating systems in the country. SWH units were installed in a large number of households, hotels, schools and hospitals. SWHs can be used to preheat water for more extreme temperature requirements or in medium temperature usage conditions in the commercial and industrial sectors.

GOB incentives targeted the installation of SWHs in households, hotels, and for medium temperature usage requirements in the commercial and industrial sectors.

Hotels that borrowed from the government-run Development Bank were compelled to carry out energy audits. These audits usually suggested the use of solar water heaters.

Indirect beneficiaries are energy auditors and plumbers or building contractors who take advantage of the GOB directive which compels hotels that borrow from the government-run Development Bank to carry out an energy audit and are advised to install solar water heaters.

The P&M is adequate to address above mentioned barriers as the fiscal incentives shortened the payback period of the investment into solar water heating systems, reduced the risk associated with their purchase and made them competitive with the conventional electric and gas water heaters by placing a 60% consumption tax on these technologies to strengthen the demand for solar water heaters. On the supply side the producers gained import preferences that allowed them to manufacture solar water heating systems benefiting from subsidised costs of raw materials.

GOB adopted a number of measures for the diffusion of solar water heaters including establishing fiscal incentives to consumers on installing solar water heaters, exempting producers of SWH systems from import tariffs, placing a consumption tax of 60% on the electric and gas water heaters. Hotels that borrowed from the government-run Development Bank were held accountable for their energy use and were required to carry out energy audits. These audits usually suggested the use of solar water systems.

Furthermore, the government conducted seminars, workshops, and video recordings of success stories in collaboration with the industry to demonstrate tangible energy and operating cost savings through the application of SWH technologies.

In addition, the GOB purchased a significant number of SWHs for housing projects it carried out through the National Housing Corporation, a division of the Ministry of Housing. To enhance the consumer confidence in SWHs the manufacturers established and maintained a policy of installing only rightly sized systems suitable for their respective use. Another confidence builder was the voluntary testing of a 66-gallon unit at the Florida Solar Energy Centre.

A planned interaction between above measures was built in the design of Barbados SWH Program.

The programme has two innovative elements.

Yes, the P&M could be optimized.

Tax cuts and financial incentives established to induce the SWH industry and consumers have been in place since 1974. During this time period,the incentives twice became either completely rolled back or questioned for their justification. In 1985, the Ministry of Finance in Barbados questioned their justification when the country’s economy was experiencing structural adjustment difficulties caused by the second world oil price crisis. However, the industry was rescued thanks to a World Bank financed Energy Conservation Project and its component, the Barbados Energy Awareness Program. In 1993, again the structural adjustment problems resulted in the suspension of many homeowner benefits including the income tax incentives on home repairs and solar water heaters installation.

These events point to the need for sustainable development of the SWH industry. An option could be to use regulations to make it a condition for the property developer to install solar water heaters in all new buildings. This would help the industry grow despite the withdrawal of incentives in difficult economic conditions.

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement Incentives and measures to promote Solar Water Heating in Barbados:

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

Ministry of Finance to supervise the implementation of income and tax incentives.

Funding

The treasury allots funds for different rebate schemes and consumers, and also for the industry, for example US$5000 was allotted per year under the 2008 modified Income Tax Allowance for Home Improvement. Out of $5000 up to $1000 can be used for energy audits and under the Energy Conservation and Renewable Deduction, homeowners can claim a reduction of 50 percent of the cost of retrofitting a residence or installing a system to produce electricity from a source other than fossil fuels (UNEP, 2012).

Other pre-conditions

A consumption tax of up-to 60% on all electric and gas water heaters is charged in order to make their purchase unattractive.

Barbados’s over-reliance on imported fossil fuels provides an impetus for the country to explore renewable energy options (Moore, W. et al., 2012). Through a project with church members, the first solar water heating unit was introduced in Barbados in 1964. However, the commercial break-through started during the first oil crisis with a small solar thermal industry in the early 1970s (Schwerin A. 2010, p. 34). Energy security considerations coupled with promising technology and cost-effectiveness were the driving factors for the government to establish policies and fiscal incentives to diffuse SWH in the country.

The Government of Barbados (GOB) introduced the first Fiscal Incentives Act in 1974. The Act eliminated import tariffs on the raw materials required for the local manufacturing of solar water heaters. At the same time, a consumption tax was imposed on all electric water heaters and this made their purchase less attractive. Meanwhile the National Housing Corporation, a division of the Ministry of Housing included solar water heaters for its housing programme, which signalled that there was a promising market for solar water heaters. Such concessions were necessary for the start-up of incipiant Barbadian SWH industry.

Despite the support given to the SWH industry by the aforementioned measures, high installation costs were becoming a barrier to the diffusion of units within the Barbadian consumers. In 1980, the government implemented Household Tax Benefits for solar water heaters and modified them in 2008. A sum of US$5000 per year was allotted for Income Tax Allowance for Home Improvement under the modified Income Tax Allowances in 2008. Up to $1000 of the $5000 per year of the Income Tax Allowance can be used for energy audits. In addition under the Renewable Energy Deduction, consumers can claim 50 per cent of the costs for installing a system, which produces electricity from a source other than fossil fuels. Homeowners who install solar water heaters also qualify for deductions under the Income Tax Allowances (UNEP 2012).

Quantified target

The P&M had no concrete quantified target. However, the government is committed to enhancing the contribution of renewable energy to the country’s primary energy.

International co-operations

Canadian funds through Barbados Institute of Management and Productivity (BIMAP) and Christian Action for the Development of Caribbean (CADEC)’s financial support played a crucial role in the entrepreneurial start-up of the solar water heater industry (United Nations/Economic Commission for Latin America (UN/ECLA), n.d.).

In 1985, the Ministry of Finance in Barbados questioned tax incentives when the country’s economy was experiencing structural adjustment difficulties caused by second world oil price crisis. However the industry was rescued thanks to a World Bank financed Energy Conservation Project and its component, the Barbados Energy Awareness Program.

Actors responsible for design

Central treasury approves and amends fiscal incentives. Energy Division of the Ministry of Finance, Investment, Telecommunications and Energy is in charge of initiatives to enhance the awareness of the population about renewable energy technologies and their benefits.

Actors responsible for implementation

Ministry of Finance (MoF) is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the Income Tax Allowances for home improvement, which target homeowners. The MoF also supervises economic incentives, which are given to the SWH producers.

Monitoring

Ministry of Finance monitors the Income Tax Allowance and Fiscal Incentives.

Evaluation

Yes, an ex-post evaluation including economic benefits and costs is available:

Perlack & Hinds (2003), Evaluation of Renewable Energy Incentives: The Barbados Solar Water Heating Experience,http://solardynamicsltd.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/SWH-report1-2.pdf

Evaluation results can be found in the Policy impact section of this good practice example.

Design for sustainability aspects

A positive effect on the overall economy of the country is the creation of employment opportunities in manufacturing, retail sales, and business administration as well as solar water systems design, installation and maintenance.

The following barriers have been experienced during the implementation of the policy

In 1993, the Homeowner Tax Benefit for installing solar water heaters was withdrawn due to the structural adjustment difficulties caused by the second world oil price crisis. This threatened the incipient solar water heating industry.

The following measures have been undertaken to overcome the barriers

The tax incentives were restored in 1996 when the economy recovered from the structural adjustment problems.

Concrete figures in energy savings/year

Perlack and Hinds (2003) assumed that SWHs displaced at least 50% of electric water heaters with each SWH saving an estimated 3710 kWh annually in Barbados. This saving estimate is based on a historical average tank size of 62 gallons, an operational efficiency of 90% and a water temperature change of 60ºF. The product of cumulative installations per unit energy savings and an electric water heater displacement of 50% provide an estimate of SWH energy savings. Perlack and Hinds (2003) estimate is that Barbadian SWHs are saving at least 65 million kWh annually with a ratepayer value of $BD 23 million (€9 million approx.).

Cumulative value of energy savings through year 2002 thus reaches $BD276 million (€110 million approx.).

Oil cost savings to the national economy were estimated to be at least $BD 6 million in 2002 (Perlack and Hinds, 2003).

Perlack and Hinds (2003) estimated the total tax costs of the SWH incentives at about $BD 21.5 million through 2002 (€8 million approx.).

The homeowner tax deductions account for about two-thirds of the government costs of the SWH incentives, while the tariff exemption on raw materials accounts for one-third of the costs.

At income tax rates averaging around 30 %, the cost to the investors of water heaters may have been around €25 million.

It was estimated that Barbadian SWHs had annual savings of at least 65 million kWh which amounts to a ratepayer value of $BD23 million (€9 million approx.). Average domestic electric rates were used to determine the monitory value of kWh energy savings (Perlack and Hinds 2003, pp. 3-4).

The policy is very cost effective. Cumulative SWHs energy savings (at least 65 million kWh annually with rate payers value of $BD 23 million (€9 million approx.) or $BD 267 million – €110 million approx. – through 2002) substantially exceed the tax costs of the incentives ($BD 21.5 million through 2002) – €8 million approx. At income tax rates averaging around 30%, the cost to the investors of water heaters may have been around €25 million. Oil cost savings to the national economy were estimated to be at least $BD 6 million in 2002, so their cumulative value through 2002 was already higher than the cost of the solar water heaters by then, with further savings to be expected over the useful life of the water heaters. The simple payback time to homeowners and hotels is less than two years when replacing electric water heating (Perlack and Hinds, 2003; partly own calculations based on this source).

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy