For the Cuban government energy efficiency is the main strategy to decrease energy import dependence and to reduce the number of blackouts, both of which affect the country’s socio-economic development negatively. One of its main energy saving instruments has been the exchange of old, energy-inefficient appliances and building equipment with energy-efficient ones as a part of the “Revolución Energética”. Some pieces of equipment such as light bulbs and fans were exchanged and distributed for free, while energy-efficient refrigerators had to be financed by households. For low-income households, soft loans were offered.

According to Seifried (2013), among other things, 9.5 million energy-efficient light bulbs, one million energy-efficient fans and 2.5 million energy-efficient refrigerators were distributed, resulting in annual energy savings of 1,564,263 MWh/yr, or of 20,602,005 MWh if the individual life span of the three product groups is taken into account. Based on these data, the benefit-cost ratio is calculated to be around 10.5 with cost savings of EUR 4,120 million during the life span. For these product categories, the market penetration reached close to 100%.

Note that there is a lack of data and some results are drawn from Cuban institutions (like Unión Electrica) and their accuracy was not verified.

One central programme in this context was the appliance replacement programme. To replace the inefficient refrigerators, Cuban technicians were trained in order to get experience with the new technologies. The replacement programme was coupled with a recycling programme. Many thousands of old refrigerators are taken to junkyards, where technicians recycle the products. According to the government, the refrigerators weigh an average of 122 pound, including 93 pounds of retrievable steel, 18 of plastic, 3 of aluminium and 2 of copper. The steel goes to plants like Antillana de Acero in Havana, where it is transformed into construction material. The copper goes to the Empresa Conrado Benítez to produce telephone and electric cables. The aluminium is used to make kitchen utensils and parts for other appliances (NY times 2007).

Furthermore since 2006, 13,000 social workers have visited homes and businesses, teaching people how to use the new appliances and spreading information how to save energy. In order to involve the public in the effort to save energy, an energy education initiative was put into place. The Programa de Ahorro de Energia por la Ministro de Educacion (PAEME) is a national energy programme, which was implemented by the ministry of education in 1997. The programmes introduced education programmes for students, workers and communities (United Nations 2010). In schools, energy-related topics are present in different disciplines like physics, economics and environmental courses. PAEME has also held energy festivals to educate the participants about energy efficiency (Guevara-Stone 2009).

Moreover, there is no advertising for commercial products in Cuba; instead you see billboards promoting energy efficiency and energy conservation. There was also a weekly television show and several articles were published in newspapers to promote energy-efficiency. In 2007 more than 8000 articles and TV spots related to energy efficiency issues were published (see table 1).

| Year | Newspapers | Radio | Television |

| 2006 | 610 | 5,515 | 685 |

| 2007 | 629 | 5,919 | 1,670 |

| 2008 (incomplete) | 173 | 1,952 | 690 |

Source: Arrastia Avila & Guevara-Stone

Key actors are several political-institutional organisations (Ministries, National Electricity Union etc.) and a national energy efficiency and saving group. In 2007 Cuba formed an advisory group to coordinate the energy efficiency programmes. Nowadays it includes 15 working groups that are planning national strategies to develop renewable energy technologies and to increase energy efficiency (Arrastia-Avila et al. 2009).

Seifried (2013, p. 11) estimates annual energy savings for different appliances to be:

• Light bulbs: 354,123 MWh/yr

• Fans: 62,640 MWh/yr

• Refrigerators: 1,147,500 MWh/yr

• Total: 1,564,263 MWh/yr

The “Revolución Energética” is unique in the world but there are several refrigerator replacement programmes available with the aim to replace and recycle old, inefficient refrigerators with new products. An example is the Brazilian refrigerator exchange programme – see the bigEE good practice file for this programme.

Cuba is a planned economy and the government intends to serve the interests of the majority of the working people (Cameron 2009). The Cuban government intends to motivate “people power” to achieve a goal.

This was crucial in the beginning of the 21st century when an already poor electricity infrastructure was devastated when hurricanes hit the country in 2004 and 2005. Seifried points out that during 2005, there were large blackouts on 224 days. As electricity is vital for social and economic development of every country, the “Revolución Energética” was proclaimed.

Cuba’s ties with the Chinese government, having been established since the 1980s, proved beneficial to both. For China it has been an opportunity to expand a foreign market. Cuba, where Chinese appliance manufacturers have been operating, is also seen as an economic hub for the whole Latin American continent.

Due to these ties and the traditionally rather bad relations with the OECD world, China was probably the best option for Cuba to support the appliance exchange programme discussed here (Hearn 2009, p. 3).

The aim of the “Energy Revolution” was to raise the Cuban`s capacity for electricity generation, to reduce the number of blackouts and to decrease energy import dependency. Another aim of the programmes was to save money.

To reach these overaching aims, the “Energy Revolution” aimed at exchanging most or the whole stock of inefficient residential lighting and appliances to energy-efficient new light sources and appliances. Some pieces of equipment such as light bulbs and fans were exchanged and distributed for free, while energy-efficient refrigerators had to be financed by households. For low-income households, soft loans were offered.

It is a national policy.

By exchanging energy wasting appliances and pieces of building equipment with energy-efficient ones, the Cuban government has been seeking to increase Cuba’s energy efficiency. Measures to achieve this goal were replacement programmes and information and education campaigns.

There must have been technical requirements for each product group. However, information is not available to shed a light on this issue.

Seifried (2013, p. 8) estimates new refrigerators consume 350 kWh each year.

Although the renewal of old appliances and pieces of building equipment has been an important pillar, the “Revolución Energética” is more than this one measure.

First, to replace the inefficient refrigerators, Cuban technicians were trained in the different stages of the refrigerator production line. Study tours to gather experience were carried out (Belt 2007).

Second, the exchange of energy-inefficient refrigerators was coupled with a recycling programme for this product group. Many thousands of old refrigerators were taken to junkyards, where technicians recycle the appliances (NY times 2007).

Third, training measures were integrated neatly into the “Revolución Energética”. Since 2006, 13,000 social workers have visited homes, and factories taught people how to use their new products and spread information.

Fourth, in order to raise the population’s awareness to Cuba’s energy efficiency challenge, an energy education initiative was implemented. The Programa de Ahorro de Energia por el Ministro de Educacion (PAEME) is a national energy programme introduced by the ministry of education in 1997. Its objective is to teach students, workers, and communities about energy-saving programmes and renewable energies. PAEME has studied different classes (school and university) and inserted energy issues into their curricula (United Nations 2010). The programme has also organised energy festivals to educate thousands of Cubans (Guevara-Stone 2009). Another tool of the awareness raising campaign has been a printing on Cuba’s ten pesos banknote.

Fifth, a media campaign complements awareness-raising activities. There is no advertisement for commercial products on Cuban highways; instead you see billboards promoting energy savings. There was also a TV show with energy-related issues, and articles were published in national newspapers. In 2007 alone there were more than 8000 articles and TV spots related to energy efficiency issues.

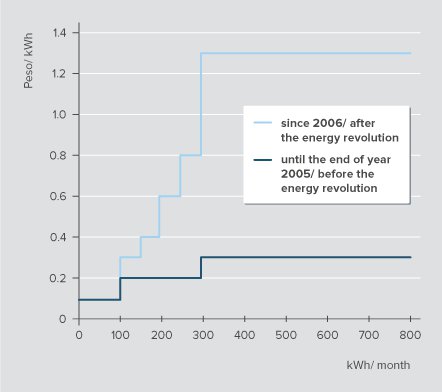

Sixth, financial disincentives were established in order to limit the overall energy consumption of households. A new tariff structure allows people who consume less than 100 kWh per month (first tariff zone) to stay at the current low rate of 0.09 pesos/kWh (0.3 Eurocents/kWh). For the second tariff zone (101 and 150 kWh/month) consumers pay 0.3 pesos per KWh, which is an increase of 0.1 pesos per kWh. The tariff structure increases systemically, but is capped at 1.3 pesos per KWh for consumers of more than 300 kWh/month (sixth tariff zone).

Some aspects of the policy package can be regarded as innovative.

The most innovative feature is probably the approach to target virtually 100 % exchange of old, inefficient light bulbs and appliances through a combination of free delivery for some goods, bulk purchasing to reduce cost, and making the exchange mandatory. The later is of course a very strong provision that may not be feasible everywhere. While the exchange of light bulbs and fans with energy-efficient ones was completely free of charge for consumers, these were obliged to purchase energy-efficient refrigerators. Although little information about opposition to this coercive policy exists, resistance may have been mitigated by offering soft loans to low-income households.

Moreover, the government tried to pro-actively persuade the population about the benefits of the appliance exchange by using information and educational measures.

This informational and educational campaign was carried out (to an extend, which is not covered in the literature examined here) by social workers and volunteers. This is an innovative way to limit the impact of policy implementation costs on the public budget.

Capacity building measures for the local technicians can be regarded as a valuable add-on. Eventually, this may increase Cuba’s competitiveness on the global market for energy-efficient appliances.

Moreover, the credit deal with China and, thus, provided products by Chinese manufacturers offers the opportunity to carry out a “big push towards energy efficiency”.

Most importantly, Cuba did not opt for the most energy-efficient appliances (BAT), so this is a lost opportunity for even higher energy and cost savings.

Also the policy package can be optimised: Providing the entire population with energy-efficient appliances in one step will leave almost no domestic demand for the respective appliances for roundabout the life span of the product. This is a likely to be serious problem for building up a sustainable domestic production of appliances.

Informing the remaining demand on energy efficiency via an appliance-labelling scheme together with financial incentives only for BAT or nearly BAT products would be important for future energy efficiency improvements.

International cooperation with e.g. the Global Environment Facility can, among other things, enhance the innovation potential of Cuban domestic appliance suppliers.

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement the “Revolución Energética”

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

Key actors are several political-institutional organisations (Ministries, National Electricity Union etc.) and a national energy efficiency and saving group. In 2007 an advisory group for the purpose of coordinating all actions related to energy efficiency was formed.

The implementation of the policy, i.e. the exchange of old appliances with energy-efficient ones, rested to some extend on the shoulders of social workers and volunteers.

Funding

The funds for the energy efficiency programmes come from national budget. The Cuban government has invested several billion pesos in the “Energy Revolution” (United Nations 2010).

According to Seifried (2013, p. 23) almost every product purchased by the Cuban government from China within the framework of the “Revolución Energética” were financed via a large credit deal between the two actors. Presumably, credits can be served via energy import savings.

In addition the Cuban government received economic aid from Venezuela and Russia, which gave Cuba a $350 million credit package. The money was partly used to upgrade the energy and transportation systems. A large part of Cuba´s revenues now comes from tourism, which helps to finance many of the energy programmes.

Other pre-conditions

A stable political system able to circumvent people’s opinion also helped implement the “Energy Revolution”.

Quantified target

The targets vary regarding the product category. For example, the goal for refrigerators was to exchange and recycle 100% of all old, energy-inefficient refrigerators (consuming around 800 kWh per year) with efficient appliances (consuming around 450 kWh per year). That was due to their large share (around 50%) on a Cuban household’s overall energy consumption. Similarly, the government aimed to exchange 100% of all old light bulbs.

Further product categories were also exchanged, but literature available gives no indication whether the government of Cuba set any targets for these appliances.

International co-operations

China, which has several appliance manufacturers located in Cuba, was the primary partner for this policy.

Furthermore Cuba has exported its experiences to other countries like Venezuela and Bolivia. Cuban scientists and technicians have also installed solar electric panels in Venezuela, Bolivia, Honduras, South Africa, Mali and Lesotho (Guevara-Stone 2009).

Actors responsible for design

Key actors are several political-institutional organisations (Ministries, National Electricity Union etc.) and a national energy efficiency and saving group.

In 2007 an advisory group for the purpose of coordinating all actions related to energy efficiency was formed. Nowadays there are fifteen groups that are working on national strategies to develop renewable energy technologies and to increase the energy efficiency (Arrastia-Avila et al. 2009).

Actors responsible for implementation

To some extend social workers and volunteers implemented the exchange of energy-inefficient products like light bulbs.

Monitoring

N/A

Evaluation

Seifried (2013) provides a rough evaluation of the policy, including energy savings, costs, and benefits. For results, please see the policy impact section (tab).

Design for sustainability aspects

The refrigerator replacement programme was coupled with a recycling programme. Many thousands of old refrigerators are taken to junkyards, where technicians recycle the products. According to the government, the refrigerators weigh an average of 122 pound, including 93 pounds of retrievable steel, 18 of plastic, 3 of aluminium and 2 of copper. The steel goes to plants like Antillana de Acero in Havana, where it is transformed into construction material. The copper goes to the Empresa Conrado Benítez to produce telephone and electric cables. The aluminium is used to make kitchen utensils and parts for other appliances (NY times 2007).

Co-benefits

In particular, the exchange of kerosene- or liquefied gas-based cooking stoves with electricity-powered ones increased the indoor air quality and reduced the risk of fire for some households (Seifried 2013, p. 9).

China, which is the primary for the policy, has several appliance manufacturers located in Cuba. Whether the increased demand for their products has contributed to the labour market, is unknown.

Moreover, since 2006, 13,000 social workers have visited Cubans, replacing light bulbs, teaching people how to use their new products and spreading information. However, whether this has created any positive labour market effects, is open to speculation, too, as no robust information exists.

The following barriers have been experienced during the implementation of the policy

Due to information restrictions set out by the government, there is hardly any information available regarding barriers to implementation. Seifried (2013, p. 23) refers to discontent within some parts of the population because of increasing electricity consumption due to the exchange of electric cooking stoves by kerosene- or liquefied petroleum gas-fuelled cooking stoves. As new refrigerators are estimated to save roughly 450 kWh per year compared to old refrigerators, net electricity savings should outweigh new costs.

There is no information about people’s discontent regarding new loan-obligations.

Moreover, the content of the agreement between Cuba und China is unknown.

The following measures have been undertaken to overcome the barriers

Cuba has combined the mass roll-out of energy efficient appliances with education campaigns and provision of information through mass media. Print media, radio, and television inform its audience on energy issues.

The United Nations made a quantitative assessment of achievements due to the “Energy revolution” (United Nations 2010). According to these calculations, the “Energy Revolution” yielded an overall saving of 2.365 million tons of oil equivalent from 2006 to 2008.

More specifically, Seifried (2013, p. 11) estimates annual energy savings for different appliances to be:

• Light bulbs: 354,123 MWh/yr

• Fans: 62,640 MWh/yr

• Refrigerators: 1,147,500 MWh/yr

• Total: 1,564,263 MWh/yr

Including the life span of the individual products of 8.3 years, 7.0 years and 15 years, respectively, energy savings are assumed to be:

• Light bulbs: 2 951 025MWh

• Fans: 438 480 MWh

• Refrigerators: 17,212,500 MWh

• Total: 20,602,005 MWh

According to Seifried (2013, p. 7f.) average energy savings for refrigerators (as compared to the energy-inefficient products that were replaced) are 450 kWh per year, down from 800 kWh for an average Cuban refrigerator that was replaced.

If effectiveness is measured against the target to provide 100% of all Cuban households with energy-efficient appliances/building equipment, the programme can be considered highly effective. The following figures show the share of exchanged appliances (which are energy efficient) to the total appliance stock (Seifried 2013, p. 8):

• Light bulbs: 100%

• Fans: 100%

• Refrigerators: 96%

• Television: 22%

Note that data are drawn from Cuba’s Unión Electrica and we have no means to verify their accuracy.

Seifried (2013, p. 11) roughly calculates for the exchange of fans and refrigerators costs of EUR 10.4 million and EUR 383 million, respectively.

While costs for the exchange of fans as well as light bulbs were financed by the public purse, costs for new refrigerators had to be covered by individual households. Costs for refrigerators were around EUR 180 per refrigerator. Low-income households are offered low-interest loans (Seifried 2013, p. 8).

Cost saved for the life span of the individual products are (Seifried 2013, p. 11):

• Light bulbs: EUR 590 million

• Fans: EUR 88 million

• Refrigerators: EUR 3,443 million

Total: EUR 4,120 million

Based on the given data, Seifried (2013, p. 11) expects a benefit-cost-ratio of 10,5 (or EUR 393 million: EUR 4,120 million) for the exchange programmes for fans and refrigerators (investments costs for lights bulbs were not determined).

Further information

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy