Energy prices should ‘tell the economic and ecological truth’ through full-cost pricing or the internalisation of external effects in order to discourage wasteful consumption of environmental resources. Therefore, existing inefficient subsidies for non-renewable energy production or on energy prices should gradually be removed - legislators and governments should rather use the budget saved to fund energy efficiency schemes for low-income households and small businesses, so as to keep their energy bills affordable instead of maintaining energy prices at artificially low rates.

Removing inefficient energy subsidies is a necessary and effective measure to overcome distorted energy prices, to change incentive structures in the energy sector and give to energy efficiency investments the value they deserve. The removal of energy price subsidies will let market prices reflect the true (i.e. social) cost of energy production and consumption more accurately. The policy thus supports the creation of favourable market conditions for energy efficiency investments. In this way, private investors will see the same value and benefits of energy efficiency as the national economy as a whole. In addition, removing energy subsidies will generate budgetary savings. Consequently, governments gain additional financial scope to finance energy efficiency policies and measures.

Although energy subsidies can in theory help to overcome distributional imbalances, poor design and/or implementation as well as interaction with other fiscal measures often leads to distortionary effects on energy markets. Subsidies on energy supply protect energy producers from competitive market pressures and thus reduce incentives to operate more efficiently. This may impede efficiency investments as well as development and in consequence the market entry of more energy efficient technologies. Likewise, across-the-board energy consumption subsidies are not only unsuitable for achieving social targets like alleviating energy poverty (cf. OECD & IEA 2011) but they also induce wasteful consumption of environmental resources and energy products. In light of these undesirable outcomes, the removal of inefficient energy subsidies is reasonable from an economic, environmental and social point of view.

The total amount of global subsidies is huge – with regard to fossil-fuel-related consumption the IEA estimates up to US$ 409 billion in 2010 (cf. OECD & IEA 2011). With regard to fossil-fuel-related production the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) estimates around US$ 100 billion in 2009 (GSI 2009). The level of subsidies and primary energy demand are closely linked to volatile fossil-fuel prices and macroeconomic developments. Therefore, predictions regarding monetary and energy saving potentials from removal of energy subsidies are difficult. Nevertheless, according to IEA analysis, phasing-out the lion’s share of subsidies related to fossil-fuel consumption could lead to a 5.8% reduction of primary global energy demand by 2020 compared to a business-as-usual scenario (cf. IEA et al. 2010). Global CO2 emissions are estimated to decrease by 6.9% (equal to 2.4 GT of CO2) over the same period due to implementation of the policy.

However, notwithstanding a compelling rationale, attempts at policy reform or termination often face fierce political resistance from affected stakeholders, particularly if there are substantial financial entitlements involved, as is the case with subsidies. If associated budgetary savings are for the most part dedicated to energy efficiency programmes or policies though, it can facilitate the process by generating necessary political support. Moreover, gradual implementation can minimize adjustment cost for target groups and thus further improve the political feasibility of subsidy reform policies.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

The removal/reform of inefficient subsidies on end-user energy prices aims at changing energy consumption patterns towards reduced or more efficient energy use and ending costly and inefficient spending of public funds. By reforming subsidy schemes that push energy prices below market level, energy subsidy removal/reform profoundly changes incentive structures for end-users and producers alike, thus giving energy saving behaviour and energy efficiency investments the financial value they deserve. By this, private investors will see the same value and benefits of energy efficiency as the national economy as a whole.

At their summit meeting in Pittsburgh in 2009, the leaders of the Group of Twenty (G-20) countries agreed to phase-out inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies over the medium term (cf. www.bigee.net/s/61f6gv). However, when reviewing those commitments, independent studies have found little progress made in terms of real action (cf. Koplow 2010; G20 Research Group & G8 Research Centre 2010; Koplow 2012). Reported efforts had been initiated prior to the commitments and information on the scale of existing subsidies has suffered from serious underreporting. Still, it can be seen that many developing countries and emerging economies are also taking action to reduce energy subsidisation.

Since direct or indirect subsidies on end-user energy prices and on energy supply are being implemented at all levels of government (international, national, regional and local), their removal/reduction likewise occurs on all levels.

Depending on the incidence of a subsidy, all sectors (industrial, commercial, residential and public) are potential targets.

Overall, society benefits from a decrease in inefficient spending of public funds and - very likely - also private funds, due to decrease in energy wastage.

Overall, society benefits from a decrease in inefficient spending of public funds and - very likely - also private funds, due to decrease in energy wastage.

If due to market failure energy prices still do not reflect the social cost after a subsidy reform, it should be complemented with other fiscal measures such as energy taxation. Moreover, besides setting negative incentives for more efficient energy use and production, a policy package should comprise regulatory measures such as Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) for products and processes, financial incentives for energy-efficient buildings and appliances where useful, and additionally provide information (e.g. via labels or campaigns) and consultancy on how to improve energy efficiency.

The implementation of subsidy reform may require the development of institutional, administrative and sometimes physical capacity in order to gather and process information on subsidy incidence and the economic, social and environmental impact of subsidy reform, and to administer the process in a transparent manner.

Quantified target

Removal/reduction of inefficient subsidies can aim at quantified budgetary and energy savings. The scope and likelihood of emergence however are largely dependent on national circumstances with regard to subsidy patterns and the corresponding reform design.

Co-operation of countries

Multilateral agreements on reforming national energy subsidies can legitimise the policy within the public discourse and have an important signal effect to opposing domestic stakeholders. Moreover, internationally co-ordinated action can prevent competitive disadvantages for national industries and energy suppliers, as well as transnational shifts in consumption.

Monitoring

For the purpose of evaluating the removal of energy subsidies, a broad database of factors that influence energy consumption is necessary, which should be built parallel to the introduction of the policy. It is similar to monitoring and evaluating the introduction of an energy tax. Best evaluation practice has shown that for the assessment of energy consumption on a household level, monitoring of data not only on total energy consumption, but also on the use of appliances, general behavioural patterns, type of household by size and income are most useful, while on an industry level data on the overall consumption of different sectors is sufficient (cf. INFRAS 2007, p. 19). For the tertiary sector, the type of business or building should also be monitored.

Furthermore, both the actual energy prices after subsidy reform and the level of subsidy before and after intervention should be monitored as a basis for evaluating their impact on energy prices.

Evaluation

In order to evaluate the different impacts of a policy-induced change in energy prices, the use of Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models and other econometric approaches such as time series analyses - before and after introduction of the schemes - to evaluate energy price elasticities of energy demand and to calculate the energy savings using these, but also Input-Output-Analyses, have proven to provide sound and meaningful results. Overall, rather than the choice of method, the availability of relevant data is crucial in this respect. With regard to timing, impacts on the energy demand side should be evaluated within 1-3 years after the introduction of the instrument while structural impacts require a longer period of 5 years to emerge (cf. INFRAS 2007).

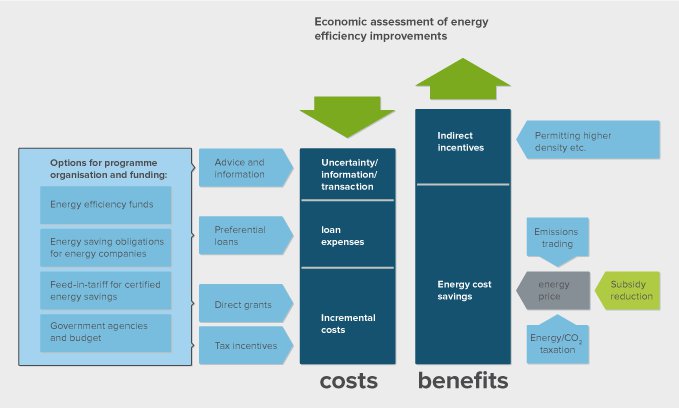

Impacts that should be considered are, on the one hand, the additional costs to energy consumers from the increase in energy prices but also from energy efficiency investments induced. On the other hand, there are the financial savings from energy savings, reduced social security cost or reduced other taxes, or direct compensation payments or financial incentives received for energy efficiency investments that the state pays out of the budget savings from reduced energy subsidies.

Energy (cost) savings from such incentive programmes for energy efficiency can be evaluated directly using bottom-up methods.

For the overall economy, savings on energy supply and from reduced unemployment can be evaluated, but also wider changes in GDP. Reduced greenhouse gas emissions are another important benefit that should be evaluated.

In addition, it is useful to quantify the impact on the state’s budget. This includes not only the tax or auctioning revenue and its use, but also secondary effects from reduced unemployment or increased VAT on energy efficiency investment.

Sustainability aspects

Within a successive process of reforming inefficient energy subsidies, policy-makers should first focus on cutting fossil-fuel subsidies in order to promote energy efficiency and also renewable energy sources. This can help the transition towards a sustainable energy supply system. Moreover, by removing subsidies on primary energy, the policy may provide incentives for more efficient energy conversion and thus improve resource efficiency.

Co-benefits

The reform of subsidies on carbon intensive energy sources reduces their competitiveness vis-à-vis renewable and low-carbon energy sources, which provides society as a whole with public health benefits due to air quality improvement.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy:

Attempts at reforming financial entitlements such as energy subsidies are likely to create fierce political opposition from current beneficiaries. In addition, fear of negative economic consequences and social distortions may further shape the public discourse towards maintaining the status quo. Moreover, in practice there is often a lack of adequate information on the incidence of energy subsidies and the scope of associated negative externalities, which hampers policy-makers’ ability to point out the positive outcomes of their reform and argue in favour of the policy. Subsidy reform may also fail due to a lack of institutional and administrative (and sometimes even physical) capacity to collect and disseminate accurate data as well as to administer the reform process in a transparent and effective manner.

The following measure can be undertaken to overcome the barriers:

In order to overcome political resistance, stakeholders and scientific experts should be consulted to increase the acceptance of the policy among those affected. Also, the proceeding should be accompanied by a sound information strategy, in which policy-makers clearly communicate the social and environmental impact and the economic costs of inefficient subsidies for society, namely the benefits of reforming them.

To overcome problems with regard to the process of effectively implementing subsidy reform, the development of institutional and administrative capacity is crucial. In this instance, drawing on the technical expertise of independent organisations is recommendable.

In order to address fear of negative economic consequences, reforms should be introduced in a gradual, programmed fashion. This alleviates the financial burden on current subsidy beneficiaries and reduces adjustment costs for affected consumers. Also the choice of an opportune moment within a favourable market (e.g. low inflation, low fuel prices) and political condition (e.g. shortly after an election) can promote the successful implementation of subsidy removal/reform and may alleviate economic concerns. Furthermore, combining the energy subsidy reform with energy efficiency programmes funded from the budgetary savings can increase the acceptance of the subsidy reform.

Finally, with regard to concerns about social distortions, saved funds should be used to provide targeted assistance to low-income households in order to keep energy bills affordable. This could include both direct balancing payments for the increase in energy costs, and technical and financial support for energy efficiency improvements. It could also include broad-based energy efficiency programmes for all sectors.

According to a study by IEA et al., phasing out the lion’s share of subsidies on fossil-fuel related consumption could lead to a 5.8% reduction in primary global energy demand by 2020 compared to a business-as-usual scenario (cf. IEA et al. 2010). Also, in the same study, global CO2 emissions are estimated to decrease by 6.9% (equal to 2.4 GT of CO2) over the same period due to implementation of the policy.

Implementation costs for governments may arise in the context of institutional and administrative capacity development necessary to collect and disseminate accurate data on subsidy scope and incidence as a prerequisite for successful subsidy reform. In the short term, formerly subsidised consumers are likely to face higher costs related to energy efficiency improvements in order to cope with higher energy charges.

In a review on studies analysing the effects of fossil-fuel subsidy reform, the Global Subsidy Initiative (GSI 2010) concluded that removing fossil-fuel subsidies will result in an average yearly growth of 0.1% in GDP in OECD and non-OECD countries by 2010 and of 0.7% by 2050. Moreover, theoretically governments could save up to US$ 409 billion (data for 2010) in consumption subsidies (cf. IEA 2011) and up to US$ 100 billion (data for 2009) in fossil fuel related production subsidies (GSI 2010).

Try the following external libraries:

| Energy Efficiency Policy Database of the IEA |

| The Building Energy Efficiency Policies database (BEEP) |

| Clean Energy Info Portal - reegle |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2025 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy