Feed-in-tariffs (FITs) have already been implemented in the field of electricity generated from renewable energies in many countries. In a similar way, a country could also offer providers of standard energy efficiency programmes or of large energy efficiency projects a fixed remuneration for every certified unit of energy saved. This could be an alternative to energy saving obligations for energy companies that creates more competition in the energy efficiency market.

No countries have implemented such FITs for certified energy savings yet. However, similar approaches, such as competitive bidding or standard offer schemes for capacity (not energy) saved through load management or energy efficiency have been realised in a number of countries.

Feed-in-tariffs (FITs) have already been implemented in the field of electricity generated from renewable energies in many countries. In a similar way, a country could also offer providers of standard energy efficiency programmes or of large energy efficiency projects a fixed remuneration for every certified unit of energy saved.

This could be an alternative to energy saving obligations for energy companies that create more competition in the energy efficiency market. While energy saving obligations for energy companies define the quantity of energy to be saved and leave the costs to the market, FITs for certified energy savings define the remuneration for energy savings but leave the quantity of savings provided to the market.

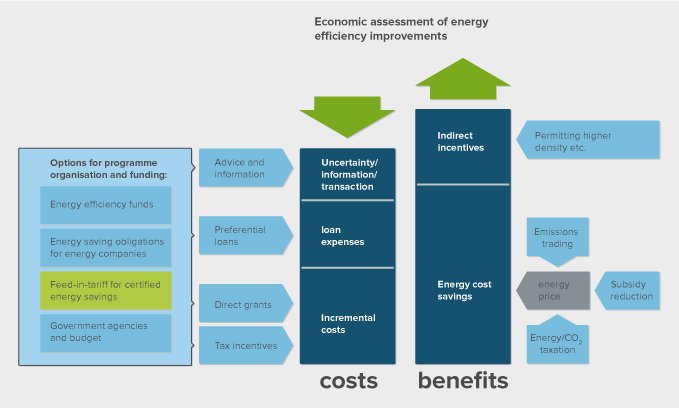

The graph shows how FITs for certified energy savings enable the implementation of different types of energy efficiency programmes that reduce costs and barriers for energy efficiency improvements.

Until now, no countries have implemented such FITs for certified energy savings to date. However, many countries have implemented or planned to introduce similar schemes, which can provide lessons for the FIT scheme development (Bertoldi et al. 2009; ESMAP & CF-Assist 2011; Neme et al. 2012; Eyre 2012). These include competitive bidding schemes for capacity (not energy) saved through load management or energy efficiency, or standard offer programmes for actors implementing larger energy efficiency projects, particularly in the USA and South Africa.

For an effective implementation, the FIT scheme should be supported by the provision of information to big end users of energy as well as to providers of energy efficiency programmes and services on its features and functionality as well as energy efficiency technologies and energy saving behaviour.

The FIT scheme, if properly designed, can be very cost-effective for the government and the society, because it requires little public funding – the costs will be paid by energy consumers as part of their energy prices if designed in the same way as for FITs for renewable energies – but results in substantial energy saving and private investment in energy saving. Based on experiences with effective an efficient programmes to date, the level of remuneration could be around 1.5 to 2 Eurocents/kWh of electricity saved, and between 0.5 Eurocents/kWh of natural gas or other heating fuel saved. However, the remuneration should differentiate between energy efficiency technologies and actions targeted, and also avoid “cherry-picking” or “cream-skimming” through increasing remuneration for higher levels of energy savings (Neme et al. 2012), e.g., for ultra low energy buildings in new build and retrofit.

As opposed to such a design, we do not recommend to simply reward reductions in the overall annual energy consumption of residential or other customers, no matter if specific energy efficiency action has been taken, as Bertoldi et al. (2009) seem to propose. Such schemes may stimulate energy-efficient or even energy-frugal behaviour. However, they also reward stochastic fluctuations in energy use and therefore create high free-rider effects.

We neither advocate setting very high financial remunerations equivalent to avoided costs of energy supply for all energy efficiency actions, as mentioned by Eyre (2012). This would give strong incentives for energy efficiency but create much higher costs than necessary for it.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

A FIT for certified energy savings aims at incentivising providers of standard energy efficiency programmes, or of large energy efficiency projects, by offering them a fixed remuneration for every certified unit of energy saved vs. a technology- or action-specific baseline. In general, energy companies or energy service companies (ESCOs) or large energy consumers fund energy efficiency programmes and projects, and sell the certified energy savings to the energy companies designated by law, just as with FITs for renewable energy. The designated energy companies recover their costs from the energy prices or tariffs paid by their customers.

Worldwide implementation status

A FIT for certified energy savings can be implemented at a national, regional, or local level. Until now, no countries have implemented energy efficiency FITs. However, some countries have implemented, or plan to introduce, similar schemes at least for larger consumers, e.g. standard offer programmes (SOP). This approach provides performance-based incentives to larger customers, paying them a certain amount per estimated kWh or kW saved through the installation of energy saving equipment in a specific programme.

Governance level

It was initially developed by regulators in the USA to encourage utilities to promote Demand Side Management activities and has also been practiced in Australia, India, and other countries. In the USA, SOPs have been instituted, in widely varied forms, in many states successfully to achieve their energy efficiency goals. They have been administrated by utilities, governmental agencies, or quasi-governmental agencies and have geared towards different customers (industrial, commercial, or residential customers). SOPs either permit (e.g., in California, New York) or require (e.g., in New Jersey, Texas) customers to work through an ESCO or other intermediaries, which plan and execute the installation of energy efficiency options. The eligibility of the projects also varies. For example, the retrofits must reduce a building’s energy consumption by at least 15% in New Jersey, while there is no specific saving requirement in other states like Texas. In general, the costs of these energy efficiency projects funded by utilities are recovered from their customers (ESMAP & CF-Assist 2011).

In 2010, the South Africa National Energy Regulator also set up a standard offer programme. Any energy user (utility customer) or ESCOs can be paid with a fixed amount per kWh or kW after the completion of the energy efficiency project and certification of the achieved savings by an authorized M&V organization. To be eligible for the payments, the technologies deployed in the project must be pre-approved by the energy supply company Eskom. The pre-approved list is not static. Technology manufacturers and suppliers are invited by Eskom to propose innovative technologies. If appropriate, these technologies will be added to the pre-approved list (ESMAP & CF-Assist 2011). The cost recovery is done through the Energy Efficiency Demand Side Management allowance that corresponds to a public benefit charge (de la Rue du Can et al. 2011).

In addition, competitive bidding schemes for energy saving have also been implemented in a number of countries. For example, in the USA, utilities that are required to achieve demand side management look for energy service companies to provide innovative solutions, with the lowest costs, through a bidding process (NRDC 2003).

In principle the technological focus is unlimited. Some building examples:

Buildings options:

For the energy companies as a main target group, the FIT scheme addresses the barrier created by conventional price and market regulation, that they earn more from increased energy consumption so that there are no recovery of energy efficiency programme costs or no reward for energy savings. However, depending on the level of remuneration, the financial incentive may be sufficient or not to break even, and regulators should monitor this and use complementary regulatory instruments to set the incentives right.

For ESCOs, the scheme addresses their barriers of uncertainty of demand, risk of business development, and availability of financing.

For the beneficiaries in the energy efficiency markets, since energy companies or ESCOs usually assist their customers with energy efficiency programmes combining information and financial incentives or with energy efficiency services, these mainly address the following barriers. The FIT scheme directly addresses them for large energy consumers participating with their own projects.

The FIT for certified energy savings can be more effective when being supported by provision of information about the FIT scheme as well as energy efficiency technologies and their costs and benefits.

Other policies, such as minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) and mandatory comparative energy labels or Energy performance certificates, or RD&D funding can provide an important basis for the energy companies and ESCOs in terms of deciding which programmes/ measures to promote. Programmes implemented for a FIT should target solutions exceeding MEPS in energy efficiency by far, such as ultra-low energy buildings. They can thus prepare the next revision of MEPS.

In general, governments need to assess and decide which energy efficiency potentials and end-use actions they want to address through a FIT for certified energy savings and the corresponding programmes and services by the energy companies and ESCOs or alternatively through an energy efficiency fund or through programmes directly offered and funded by the government (see detail on this option of government agencies and budget. This will also depend on the general performance of energy companies, ESCOs and the regulator.

FITs and Energy efficiency funds can also be used complementary to each other. For example, the fund can address fields of action that cannot be or are not addressed by the standardised energy efficiency programmes typical for a FIT scheme. E.g.: Energy companies will run standard financial incentive programmes, while funds will run motivation and information campaigns, promote innovative technologies and techniques, address behaviour, etc.

Furthermore, an Energy efficiency fund can include a smaller FIT or Standard offer programme for ESCOs and large energy consumers in its programme portfolio, as is the case with Efficiency Vermont (RAP 2012). In this case, the savings are not sold to energy companies but receive a standard remuneration from the fund.

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

A FIT administration, governmental (e.g. a department in an existing agency) or non-governmental (e.g. a committee including major stakeholders) which is responsible for FIT administration needs to be set up. Its responsibility can cover all the steps of design and preparation listed below:

In addition, independent organisations responsible for Measurement and Verification (M&V) of energy saving of a specific programme or project not using standardised should be in place.Furthermore, programme operators or project aggregators such as energy companies and ESCOs are essential for the participation of residential and small commercial customers, due to the non-trivial transaction costs (Bertoldi et al. 2009; Neme et al. 2012).

Funding

As with Feed-in-tariffs for renewable energy, the law can provide that energy grid companies must purchase certified energy savings at the fixed FIT and then distribute the costs evenly to all energy consumers in the country, who pay a certain share of their energy price to fund the costs.

A FIT scheme can also be funded by a public benefit charge, i.e. a charge added ex ante to all customers on energy consumption that is intended to cover costs related to services that an energy company provides in the public interest (Bertoldi et al. 2009).

Test procedures

The FIT scheme needs test procedures for energy efficiency in two ways: for the definition of calculation methods for the proof of energy savings achieved, and for setting and communicating energy efficiency requirements for the actions promoted in the programmes and services that the energy companies, ENCOs and others implement to achieve their targets.

The ESO will, therefore, first rely on test procedures that were generated, e.g., in the preparation of MEPS and energy labels for both purposes. However, to the extent that such procedures do not (yet) exist for some types of action, specific test procedures for energy efficiency will need to be developed for the FIT scheme.

Others

An easy-to-monitor, consistent, and unequivocal set of calculation methods for the proof of energy savings achieved needs to be developed. It must cover all energy efficiency actions eligible for the scheme.

The FIT agency and the energy companies, ESCOs and other actors need highly qualified staff with knowledge of energy efficiency solutions and potentials as well as programme design, implementation, and evaluation.

Quantified target

It is advisable to set an energy savings target for the FIT scheme as a whole, as a part of the government’s overall energy efficiency policy portfolio. The FIT scope and levels may then need to be adapted from time to time in order to ensure target achievement.

A specific standard energy efficiency programme eligible for the FIT does not need a quantitative energy savings target but we recommend it.

International co-operation

International co-operations that share best practices of the design and implementation of the FIT scheme for certified energy saving can help policy-makers at national, regional/local level to improve their policies.

Monitoring

Different Measurement and Verification (M&V) approaches exist. The simplest way is to stipulate deemed saving assumptions for certain energy efficiency options before its installation. For example, many jurisdictions in the USA have technical reference manuals documenting these savings. A more complex way is to conduct short-term tests to obtain inputs for saving calculation. A complete M&V can include whole building analysis, such as calibrated simulation modelling, or extensive metering of end-use equipment or systems. Which approach to be chosen depends on data availability, the predictability of equipment operation, and/or the trade-offs between M&V precision and cost (Neme et al. 2012).

In addition, an ex-post evaluation for the perspectives of consumers and society will require the following data to be provided by programme and project implementers. For evaluation of energy savings, the documentation should cover the number of participants or beneficiaries, the energy efficiency actions they have taken (e.g., purchase of energy-efficient buildings), and the unitary gross energy savings achieved by each action (either via agreed deemed savings or ex ante agreed calculations, or via ex-post evaluations) (cf also Staniaszek & Lees 2012). To ensure that sufficient and useful monitoring and evaluation data will be provided by the programmes or projects, the provision of this data should be part of the funding requirements to direct FIT beneficiaries.

For evaluating economic benefits and costs, energy companies and direct FIT beneficiaries need to provide evidence of their costs incurred, separately for the programme design, administration, communication and evaluation costs and for any financial incentives or project investments; confidentiality needs to be guaranteed. They must also provide the incremental part of the energy or power (kW) prices that the participants/beneficiaries would have paid for the energy or power they saved. Furthermore, incremental costs by the customers to invest in energy efficiency or operate their premises and equipment in an energy-efficient way need to be estimated via market monitoring or ex-post evaluation.

Evaluation

In order to be credible, evaluation should be done by independent institutes or consultants and costs should be carried by the government, e.g., the FIT agency.

The possibilities and formulas for evaluating energy savings will depend on the type of energy efficiency action supported as well as the type of energy efficiency programme or service (e.g., information only programmes are more difficult to evaluate than financial incentive programmes or energy efficiency services, see our detailed files on these types of policies and measures). The same holds for economic benefits and costs from either the customer/participant perspective or that of the national economy/society.

In addition to the data directly monitored for the energy efficiency programmes, evaluation of net energy savings compared to baseline trends should address side-effects such as rebound, multiplier, and free-rider effects, and the ‘lifetime’ and potential deterioration of energy savings.

For the economic benefits from the perspective of the national economy/society, standard values for the incremental energy supply costs that will be avoided in the long run for a kWh of energy or a kW of load should be developed by the government.

Sustainability aspects

In a FIT scheme, bonus payments are also an option to promote sustainability aspects other than energy savings. This could include energy savings for low-income customer groups, so as to reduce fuel poverty and promote water savings, or efficient use of materials. The specific calculation methods for energy savings could also provide bonuses e.g. for water savings for clothes or dish washers, or limits on water consumption.

Co-benefits

It will depend on the scope and design of energy efficiency programmes implemented under a FIT scheme and on the incentives as mentioned here above, what kind of co-benefits (i.e. “non-energy benefits” such as health improvement, labour market effects etc.) may arise from implementing the FIT scheme. The increasing demand of energy efficiency products and services induced by the implementation of the FIT scheme may enhance the job market in these fields.

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers:

The potential energy savings from a FIT scheme will depend on its scope. In principle, a wide scheme implemented as the main mechanism for organisation and funding of energy efficiency programmes may achieve the same level of energy savings as has been demonstrated for Energy saving obligations for energy companies and for Energy efficiency funds. This would be equivalent to around 2 % per year of the energy consumption of the targeted energy end-use sectors.

A successful FIT scheme may hardly require public funding, which is one major advantage of the FIT mechanism it shares with Energy saving obligations for energy companies. It only needs an agency to develop FIT levels and MRV procedures as well as for certification of savings and regulatory oversight to implementation.

The costs borne by the actors implementing energy efficiency programmes and services and supported by the FIT are likely to be very similar to programme costs under Energy saving obligations for energy companies or for Energy efficiency funds. They are limited to the FIT level. Based on experience with effective an efficient programmes to date, the level of remuneration could be around 1.5 to 2 Eurocents/kWh of electricity saved, and between 0.5 Eurocents/kWh of natural gas or other heating fuel saved. However, the remuneration should differentiate between energy efficiency technologies and actions targeted, and also avoid “cherry-picking” or “cream-skimming” through increasing remuneration for higher levels of energy savings (Neme et al. 2012), e.g., for ultra low energy buildings in new build and retrofit.

In this respect, a FIT scheme that is differentiated based on different factors (e.g. technologies, market segment, the depth of saving, and end-use sector) and decreases over time probably imposes lower costs for society, in comparison with more uniform supportive schemes (Ragwitz et al. 2006).

The FIT scheme can be very cost-effective for the government, given its small demand on public funding and its ability to attract substantial private investment in energy saving.

For t society as a whole, the benefits of energy saving include, avoided energy supply system costs, the improved reliability of the electricity network, postponement of the grid reinforcement, avoidance of black outs, avoidance of investments in reserve power in the case of electricity savings, and their external costs (e.g. environmental costs not covered by emission allowances) (Suerkemper & Irrek 2010; Green Alliance 2011). Thus, with a proper design, the FIT scheme can be cost-effective for the whole of society. Again, assuming similar results as for energy saving obligations for energy companies and for energy efficiency funds, it is very likely that FIT schemes will be highly cost-effective, with benefits as high as two to six times the costs.

|

|

Energy Efficiency and Demand Side Management Incentive Program

Type: Feed-in-tariff for certified energy savings |

South Africa |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy