Bulk purchasing and co-operative procurement works through gathering large buyers (private and public). It is useful for promoting very energy-efficient building technologies already available on the market (BAT) or new, even more energy-efficient equipment (‘technology procurement’). The resulting demand volumes can induce manufacturers to develop, produce and market these technologies and equipment, increase market penetration, and reduce market prices for these technologies. This in turn will lead to these technologies being used even more often and eventually becoming the default technology in new construction.

Co-operative procurement was originally developed for the demand aggregation for energy-efficient appliances. Although it can be transferred to building related technologies, it should be kept in mind that the building market is, to some extent, more sophisticated. For example, while appliances, in general, do not need experts for installation, building integrated equipment such as HVAC or circulators require experts safeguarding the proper product installation.

As an example, the Energy+ Pumps project has contributed to making highly energy-efficient heating system circulators the standard in the European Union (EU). When the project ended in early 2009, the Energy+ circulators had already achieved more than 15 % of the market for small-scale circulators sold as stand-alone units (i.e. for installation with floor-standing boilers or for replacement), and between 5 and 10 % including those built into boilers (Thomas & Barthel 2009). From 2013, such circulators that save between 50 and 80 % of electricity compared to conventional technology have been required by law in the EU.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

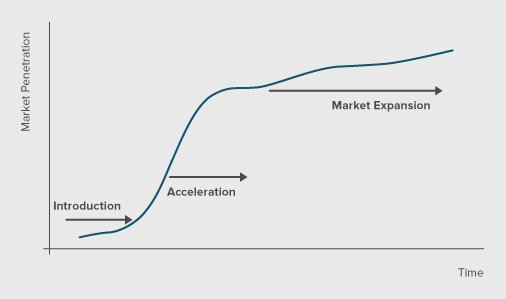

Co-operative procurement aims at the introduction of innovative energy-efficient products into commercial use, opening up new choices for investors and users (ten Cate et al. 1998). The objective can either be to increase the production and market volumes of highly energy-efficient building equipment (best available technologies—BAT)—this is called market procurement—or to bring new, even more energy-efficient technology (best not yet available technologies—BNAT) to the market—technology procurement. Co-operative procurement aims to use the market influence of a group of large buyers to stimulate the production of, and to establish a significant demand for energy-efficient products. This type of policy holds significant promise to introduce, accelerate, and expand the market for very energy-efficient building equipment.

Worldwide implementation status

One of the first technology projects was a refrigerator/freezer programme from Sweden, which started in 1989. A group was created, consisting of leading buyers. They represented about 40 per cent of the market for combined refrigerators/freezers. Purchase of a symbolic first series of 500-1,000 units of a frequently used model was guaranteed. The goal was formulated in the functional term of kWh per equivalent volume in litres and year. The newly developed refrigerator/freezers used a third less energy than the best ones available on the market before (Westling 1999). Sweden has implemented more than 50 different technology procurement projects between 1990 and 2005 (in the buildings, industry and traffic sector) (Stigh 2007).

In the EU-27, the Energy+ Pumps scheme (2006 to 2009) is regarded as a success. It contributed to creating a first market for the new generation of highly energy-efficient heating and hot water system circulators. Circulators in the EU have a very large energy saving potential of more than 30 TWh/year of the total electricity consumption. The IEA ran a number of multinational pilot schemes for technology procurement too, including one on electric motors.

Governance level

Co-operative procurement measures can be implemented on the national, transnational, regional or local level. However, on the sub-national level it might be difficult to find enough large buyers. Transnational policy designs have to cope with different legal (procurement) frameworks and languages.

Barriers relevant to sub-national and transnational policy designs can be ruled out for the national setting, which may be the most preferable way to implement a co-operative procurement scheme.

Concepts

Low-Energy Buildings

Ultra-Low-Energy Buildings

nearly-Zero-Energy / Plus-Energy Buildings

In principle, co-operative procurement schemes can be introduced for a wide range of building related technologies and even whole buildings following energy-efficient design concepts. It can of course also be used for energy-efficient appliances, cf. the policy file on co-operative procurement in the appliances section of the bigEE Policy Guide.

Although creating an entry market for building technologies through bulk purchasing and co-operative procurement is important, there must be sustainable demand for the time after the policy. A comprehensive awareness raising campaign to inform large buyers but also the public can be a valuable asset. At the minimum, information campaigns should provide information such as possible energy savings and cost-effectiveness. Local energy information centres - such as in France - can function as an important multiplier (Thomas & Barthel 2009, p. 18).

What also needs to be factored in is information and, if necessary, training and education measures for installation contractors. Firstly, installation contractors can promote energy efficient building technologies compared to conventional equipment. Second, if BAT or BNAT cannot be installed like their conventional counterparts, education and training courses or seminars are essential.

Labels and standards can also help to set energy performance requirements for the co-operative procurement and to identify the inefficient conventional technologies. Co-operative procurement programmes can in turn help laying the groundwork for future (revisions of) energy labels and minimum energy performance standards.

Ten Cate et al (1999, p. 7,329) consider the award scheme for technology procurement programmes as very important: “the main factor cited by manufacturers for participating in the competitive bidding process was not the promise of a financial incentive (totalling $30 M over several years) but rather the positive publicity

enjoyed by the ‘winner’.”

Financial support schemes should be considered too. In particular they may be necessary, if potential large buyers are hesitant to participate.

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement co-operative procurement:

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

A co-operative procurement scheme needs a co-ordinating agency identifying and approaching stakeholders (demand- and supply-side actors) and ensuring open communication between them. Moreover, it is important to understand and weigh the interests of all different actors and to find good reasons for all parties to participate. Obviously, the agency should have substantial expertise with regard to energy-efficient building technologies.

Ten Cate et al (1998) expect public agencies or energy companies to be able to live up to these expectations.

Funding

Funding is necessary for providing large buyers and manufacturers with information or technical assistance and to co-ordinate the programme (co-ordination of the different actors). If the programme is combined with a rebate programme, funding will be required for this financial incentive too.

Test procedures

A set of calculation methods to rate the innovative products and to identify the winner is required. Ideally, methods from an energy label can be used, which is what happened in the Energy+ scheme for energy-efficient circulators (Thomas & Barthel 2009, p. 8). Otherwise, the set of methods will need to be developed (and financed), as well.

Ten Cate et al. (1998, p. 7,324) structure the design of technology procurement schemes into a four stage process. A modified scheme is shown in the following paragraphs for co-operative procurement programmes:

Firstly, in the preparation stage the central co-ordination body must identify stakeholders. These are manufacturers, and investors but installation contractors should also be considered. Stakeholders should discuss energy performance levels, further non-energy features of BAT or BNAT. The central co-ordination body, e.g. an energy agency, should mediate between the supply and the demand side.

In the procurement stage “the final product requirements, test guidelines and any other specifications are announced” and stakeholders are to discuss quantities purchased.

The product development stage should be guided by a timetable in order to give planning security to the demand side.

In the final stage, products are delivered to co-operating purchasers and general marketing then commences.

Quantified target

Co-operative procurement policies are more effective with quantified targets. Concrete targets, such as the quantity of equipment that the buyers commit to purchasing, should be defined in order to calculate the energy saving potential and the achieved energy savings. “Goals and targets should also assign responsibility and timetables for data collection and progress reporting” (Harris et al. 2005).

International co-operations

Several countries worldwide have already introduced co-operative procurement programmes. Therefore co-operations are helpful for countries, which plan to implement similar measures. The co-operation can help policy makers to improve the design and implementation of specific policies.

Furthermore, in many cases manufacturers and large buyers are very fragmented in one country but markets may be international. Joint actions involving several countries can give stronger signals to develop energy-efficient products. Examples include: the European Energy+ Pumps project and the IEA’s international co-operative procurement project on electric motors.

Monitoring

In order to be effective, the implementation of co-operative procurement programmes should be monitored and tracked. The number of types of winning or qualifying products on offer, the concrete number of products purchased by the buyers group, and the energy efficiency improvements achieved should be reported to responsible authorities.

Evaluation

Responsible authorities like energy agencies or research institutions should carry out an evaluation of the energy and cost savings and the cost-effectiveness of co-operative procurement programmes. Key information includes: an overview of the building-related products purchased, the changes in the product range of suppliers as to the number, variety and (additional) costs of energy-efficient building technologies and the resulting development of the market. Other factors include: the costs for all market actors.

Design for sustainability aspects

Other sustainability aspects and environmental impacts can (and should) be part of an energy-efficient procurement programme, e.g. health aspects, productivity increased through high-quality, energy-efficient lighting or other resources such as; water and detergents. Other criteria are the consideration of SMEs, working conditions etc.

Co-benefits

Procurement programmes may create building technology with better services and may improve the competitiveness of manufacturers and purchasers’ employee productivity.

Few co-operative procurement schemes for the building sector have been implemented so far. Thus, evaluations are somewhat short on the ground.

The Energy+ Pumps scheme in the European Union (EU) estimated that modern, energy-efficient circulators save up to 80% compared to conventional technology. “Implementing this new energy saving pump technology as a European standard for circulators could save more than 60% of the circulator annual electricity use, that is more than 30 TWh/yr (Wuppertal Institute 2010).

When the European Energy+ Pumps project ended in early 2009, the Energy+ circulators had already achieved more than 15 % of the market for small-scale circulators sold as stand-alone units (i.e. for installation with floor-standing boilers or for replacement), and between 5 and 10 % including those built into boilers (Thomas & Barthel 2009). However, the exact contribution of the Energy+ Pumps scheme to this result is unknown. From 2013, such circulators have been required by law in the EU.

Co-ordination costs incurred by the 10 partners for the Energy+ pumps scheme were €1.13 million. The costs of manufacturers, purchasers, and supporters are unknown.

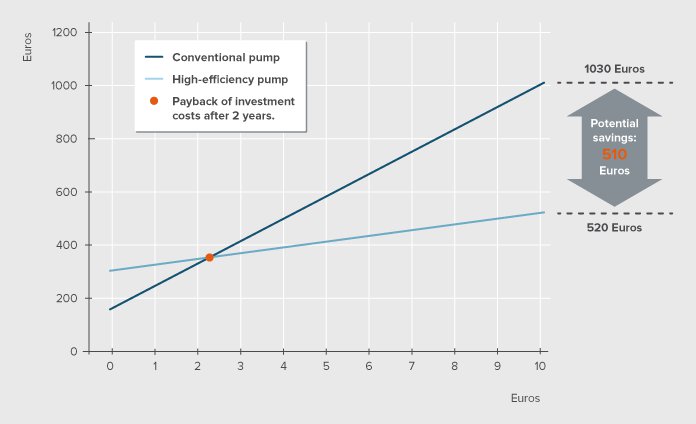

The following figure shows large scale energy cost savings for building owners and tenants, as highly energy-efficient circulators became the European standard in 2013. These save between 50 and 80 % of electricity compared to conventional technology and were promoted by the European Energy+ Pumps co-operative procurement project in 2007 to 2009. In the long run, when all circulators in the EU have been exchanged, consumers and businesses will save more than 30 TWh/yr of electricity and several billion Euros per year in energy costs.

| There currently are no good practice policy examples at this time. |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy