Building owners or investors often lack the required capital and expertise and are afraid of technical and financial risks involved in improving energy efficiency. In such cases they can outsource the financing and implementation of energy efficiency investments to third parties, such as energy service companies (ESCOs) and private or public energy companies. This is more common for energy-efficient retrofits but could also be explored for new construction projects.

Such an innovative service, however, faces its own barriers to market adoption. We therefore recommend that governments promote and support energy services such as energy performance contracting or third-party financing schemes and adopt for instance the following general measures for this purpose: providing targeted information and coaching to potential energy services customers, capacity building, standardised models and contracts, regulations such as the establishment of quality standards and certification schemes for energy service providers, facilitating energy service provider’s access to financing and creating risk-mitigating measures, creating a favourable framework condition for energy service providers’ involvement in public procurement, encouraging the establishment of an association of energy service providers and SuperESCOs.

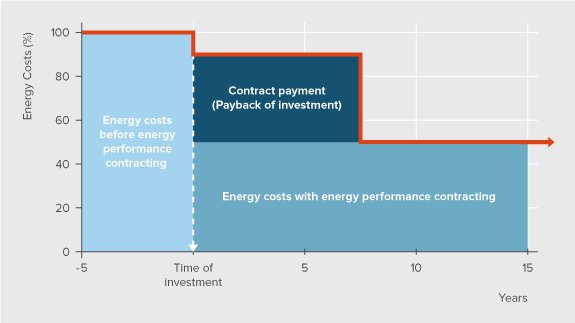

The services can be based on an energy performance contracting (EPC) model undertaken by EES providers such as energy service companies (ESCOs) and private or public energy companies. Different to just providing energy consultancy in the form of Energy audits and advice, EPC providers guarantee the savings and their profit is directly linked to the energy savings of the project. Thus, energy efficiency projects based on EPC can enable governments with tight budgets to save energy and costs, because public spending is hardly needed and ESCOs endeavour to ensure the savings.

EES and the business of ESCOs in North America and Europe are usually based on the EPC model. However, in many developing countries, EES providers are often not able to take performance risk, but rather arrange implementation of energy efficiency improvements with the client’s financing or financing by a SuperESCO (such as in India) and undertake monitoring and verification (M&V). Governments will have to analyse which model is most adapted to the national markets, and may aim to extend the EES market towards more complete services such as EPC over time.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

EES and ESCO concepts appeared for the first time in Europe more than 100 years ago (Ürge-Vorsatz et al. 2009). However, they targeted provision of heating energy at a fixed cost, not the implementation of energy efficiency improvements through EPC. The concept moved to the United States in the 1970s. It came back to Europe in the 1980s and has spread with varying success (Marino et al. 2010). The introduction of ESCOs in developing countries started in the 1990s (Ürge-Vorsatz et al. 2009).

The United States is regarded as the most mature ESCO market in the world. The ESCO market for energy efficiency project exceeded $5.1 billion in 2011. The majority of ESCO work is conducted for the public sector at the state or local level (about 73% of all ESCO activity) (Pike Research 2012). The growth of ESCO market in the USA can be attributed to a combination of enabling federal legislations (e.g. obliging Federal Agencies to reduce building energy consumption cost-effectively), public financial and other supports such as public benefit charges, existence of Super-ESCOs providing both energy and energy efficiency service, and Demand-Side-Management (DSM) program and bidding (Ürge-Vorsatz et al. 2009).

In Europe, Germany is the largest and most mature ESCO market. This has been attributed to a good mix of financial and technical support by the government, non-governmental programmes, and favourable policies in the energy sector, such as the ecologic tax reform. Municipal projects based on public-private partnerships have demonstrated the ESCO concepts and benefits, particularly when municipal budgets are tight. The success can also result from the existence of a large number of competing energy service providers, suppliers of energy efficiency products, and independent players such as energy agencies (Marino et al. 2010).

In China, the EES and ESCOs started in the 1990s through the pilot projects supported by Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the World Bank. The further enlargement of the ESCO market has resulted from the increasing attention from the governments at different administrative levels, finance incentives such as rewarding energy saving achievement by the ESCOs, the loan guarantee system, the guidance of EES industry development issued by the government, the establishment of the ESCO industry association (EMCA), etc. (Sun 2011; Murakoshi & Nakagami 2009).

Policies or measures promoting EES provision can be implemented at national, regional or local level.

Policies or measures promoting energy efficiency services (EES) in principle address all the residential, commercial, public, and industry sectors. However, in many countries the focus is on the public sector, often combining restricted investment capacities that make EES attractive for the client with a low risk of bankruptcy, which is attractive for the EES provider.

The foci of policies or measures promoting EES are very broad and can be all buildings and technologies applied in residential, commercial, public, and industrial buildings, but usually not appliances. A focus is on heating, cooling, ventilation and lighting, including solutions with high investment and low energy costs such as combined heat or cold and power or renewable energies, whereas thermal insulation is often more difficult to include due to longer payback periods required.

EES providers, such as ESCOs (Energy Service Companies) or energy companies that provide energy services, are the target group of this policy or measure. Some supporting measures also target local authorities. These measures include coaching potential customers or coaching banks as lenders of EES project finance (e.g. risk-mitigating measures like insurance funds or similar).

Policies or measures promoting EES provision is itself a policy package containing different types of policies or measures:

Information provision: providing targeted information on EES business and its good practices can increase the awareness of investors about buildings, facility managers, financial institutions, about EES provision and reduce the financial institutions’ risk perception of providing financing to energy efficiency projects. For investors and facility managers, it is also important to know how to find an appropriate EES provider. In addition, supportive information, such as the access to financing, can be given to EES providers (Suerkemper & Irrek 2010; Szomolanyiova et al., 2012).

Capacity building: capacity building programmes can be provided for financial institutions to help them to understand EES provision and learn about the lessons from international financial institutions on, e.g., risk assessment and appraisal techniques (Ellis 2010; UNEP 2007). Public administrators should also be trained to ensure sufficient internal know-how to tender EES (Szomolanyiova et al., 2012). In addition, training programmes can be provided for EES providers to strengthen their technical and management capacity (Marino et al. 2010).

Regulation: the establishment of standardisation and a certification scheme can significantly reduce transaction costs for EES providers. Standardisation can cover monitoring, evaluation, verification and reporting concepts, as well as standard documents and performance contracts (Suerkemper & Irrek 2010; Marino et al. 2010). Certifying EES providers ensures the quality of the providers and can increase the confidence of those investing in buildings, and financial institutions, in EES provision. In addition, energy saving obligation schemes that create possibilities for EES providers to sell the certified energy savings to the obligated parties can create a new modest revenues source for the EES projects. Furthermore, regulations obligating the EES providers to participate in, for example, energy efficiency projects for governmental buildings or the implementing of energy efficiency obligation in the industry, is powerful for EES market development (Ellis 2010).

Financing: policies or measures that facilitate EES providers’ access to appropriate forms of financing are crucial for EES market development. These include policies or measures such as a loan guarantee by the government, special-purpose credit lines/revolving fund, and engaging financial institutions (including public development banks) (Marino et al. 2010). Also, financing mechanisms such as revolving funds for energy efficiency can be developed to enable the EES provision in sectors characterised by high transaction costs such as in the residential sector (Szomolanyiova et al. 2012).

Financial incentives: Where financial incentive programmes for investment in building energy efficiency exist, they should be open for EES projects too. Not only the building owners or investors, but also EES providers such as ESCOs should be eligible to receive grants or other incentives.

Energy efficient public procurement: a favourable framework condition for EES providers’ involvement in the public procurement should be created, such as updating public procurement regulations, providing guidelines on how to apply energy efficiency criteria and life-cycle cost assessment in public procurement procedures, etc. (Marino et al. 2010).

Eliminating distortion: public provision of energy advice for free or at a low charge to home builders and investors may create a “competition” to the commercial EES providers but also create business opportunities for them. Thus, the policies of Energy advice and assistance during design and construction should be formulated so as to create a fair, level playing field and prepare business opportunities for commercial EES providers (Szomolanyiova et al. 2012).

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

Agencies responsible for ESCO market development, e.g. standardization and certification of EES provision, should be clearly defined.

Independent entities responsible for measurement & verification of energy saving by EES provision, to which EES contract parties can turn to, should be in place (Eubank & Browning 2004).

Financing

Policies or measures that facilitate EES providers’ access to financing are crucial for EES market development. These include loan guarantee by the government, special-purpose credit lines/revolving fund, and engaging financial (including public development banks) (Marino et al. 2010). Also, financing mechanisms such as revolving funds for energy efficiency can be developed to enable the EES provision in sectors characterised by high transaction costs such as in the residential sector (Szomolanyiova et al. 2012).

Policy-makers need to carefully assess the barriers for investment that EES could tackle but also the barriers and opportunities that EES and their providers face themselves, such as public procurement rules and regulations or access to capital.

They can then select and implement the appropriate measures to promote EES and other energy services from the list mentioned in the summary and presented in some more detail in the “policy package” section.

As with all policies and measures, monitoring and evaluation should be an integral part of implementation in order to quantify policy success and to learn if and how, policies may need to be revised and improved to be effective and successful.

Quantified target

EES provision projects have a quantified target of energy saving, which serves as a basis for the contract between EES providers and clients. For a policy or measure promoting EES provision, it is possible to specify a quantified target, such as the number of EES projects to be promoted.

Co-operation of countries

International co-operations that share best practices of EES provision as well as of policies or measures promoting EES provision can help policy-makers at national, regional/local level to improve their policies.

Monitoring

Energy consumption before and after the project completion is usually fundamental to the evaluation of the energy saving of a specific project. In general, energy consumption can be measured in the following two ways: 1) measuring the performance of specific energy efficiency measures; 2) measuring the performance of the whole building while ignoring specific equipment performance. The latter is conducted when the effects of specific measures is not easily measured in isolation, e.g. the effects of changing control and management system of the building.

On the other hand, the operation patterns of the end-uses, such as lighting, water heating and space conditioning should be recorded. For new buildings, since the first year of building operation is often unstable, the monitoring data of the second year is used for verification (Eubank & Browning 2004).

In principle, the data for management of the EES contract itself are easy to monitor. It may entail a cost for the installation and the automatic reading of additional (sub-)meters, and so a good compromise between accuracy and cost must be found.

However, these data are usually confidential between the parties of an EES contract. Policy-makers must therefore mandate EES providers, to provide these data in a way protecting commercial privacy to a designated agency, along with the implementation of policies and measures to promote energy services.

Evaluation

The energy savings are evaluated based on energy consumption after the project completion, the baseline energy consumption, and an adjustment. The adjustment includes the factors such as significant changes in floor areas, weather and operational patterns, in comparison to the pre-retrofitting case or the assumptions of the operation pattern (EPC WATCH 2007).

For energy efficient retrofitting, the baseline usually is the energy use of the situation before retrofitting, considering the occupancy patterns, equipment inventory and status, control strategies, etc. The approach of measuring the performance of the whole building sometimes assesses energy saving by comparing utility bills before or after the retrofitting. (EPC WATCH 2007).

For new buildings, since no energy use data before or without energy efficiency improvements exist, a computer model simulating the building energy consumption needs to be developed. Accordingly, a comparison can be made between the performance target of a specific design with a package of energy efficiency measures and a conventional building design or a building that just meets the legal requirements of minimum energy performance standards or energy building codes, based on assumptions of, for example, certain operation patterns and long-term weather data (Eubank & Browning 2004).

Sustainability aspects

Since energy saving is the determinant of the benefits of EES provision, the other aspects may not be actively designed and implemented. However, an enhancement of energy efficiency often improves the air quality and comfort. Thus, the health and productivity aspect is also addressed.

Co-benefits

Job creation in the EES provision field is an important co-benefit of policy or measure promoting EES provision. Indirectly, the increasing demand of energy efficiency products creates job opportunities in this field.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy

A policy package to stimulate EES should contain (cf. also PWC 2012; Suerkemper&Irrek 2010):

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers

Instruments promoting EES must be assessed for the individual case (nation, region, municipality). It goes without saying that barriers to these instruments must be detected, as well.

For example, sustainable funding for these instruments should be discussed between the stakeholders, be clearly formulated and, if support is given by the government, be legally binding. This will give planning security to the EES’s supply side as well as to its demand side.

With regard to ESCO certification, is should be made clear, who pays for the actual certification process, who (financially) maintains the certification infrastructure an so forth.

Please also refer to the section “implementation tips”.

The potentially achievable energy savings highly depends on the specific energy efficiency project design. Under the shared saving model, because their profits are directly linked to the energy savings, ESCOs endeavour to ensure that savings are as large as possible.

For example, the Berlin Energy Agency organises the „Energy Saving Partnership Berlin“. Energy savings on average have increased from around 20 % to around 30 % in recent pools of buildings that receive energy efficiency improvements via Energy performance contracting, due to the experience gained.

In some demonstration projects in German schools with higher than usual project durations of up to 20 years, it was even possible to save 50 to 60 % on electricity consumption, mainly for lighting, ventilation, and circulation pumps (Berlo & Seifried 2007).

Based on a different scenarios of policy support, Duplessis (2010) roughly estimates that the energy savings potential for energy efficiency services in EU-27 is between 582 TWh (with “low policy intensity”, LPI) and 934 TWh (with “high policy intensity”, HPI) in 2020. In the later scenario, among other things, barriers to EES are overcome by an intensive policy effort. The following table shows potential energy savings in EU-27 realisable by EES in three main sectors:

| End-use sectors | Electricity savings (TWh) | Fuels savings (TWh) | Overall energy savings (TWh) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPI Scenario | HPI Scenario | LPI Scenario | HPI Scenario | LPI Scenario | HPI Scenario | |

| Industry | 116.7 | 169.2 | 96.3 | 110.7 | 212.9 | 279.8 |

| Residential | 14.6 | 21.2 | 125.4 | 357.6 | 140.0 | 378.9 |

| Tertiary | 116.7 | 117.7 | 112.4 | 157.3 | 229.1 | 275.1 |

| All sectors | 248.0 | 308.1 | 334.0 | 625.6 | 582.0 | 933.8 |

An enabling policy environment seems to contribute to the success of EES for realising the energy saving potential of the residential sector, in particular.

The costs of EES projects are covered by and are smaller than the energy cost savings, otherwise the EES projects would not materialise.

It is difficult to give a general estimation of the cost of the policy package that promote EES provision, given it includes numerous policies or measures. However, they are usually quite small in comparison to the costs of the EES projects themselves.

The costs of energy efficiency projects vary among different projects and different countries with specific policy framework as well as for different actors. The cost of a pure EES provider mainly depends on the costs of a specific EES project. For energy companies that provide EES, the costs include the energy efficiency service costs and maybe lost revenue (e.g. lost distribution revenue), if regulators do not offer compensation. From the end-users’ perspective, the costs cover the customer payments to the EES providers for the energy efficiency project under the shared savings model. The EES costs for society as a whole cover the incremental costs for the more efficient technology paid by different actors (Suerkemper & Irrek 2010).

EES projects are usually cost-effective for customers and providers, otherwise the projects would not materialise.

Expected cost savings vary among different projects and different countries with specific policy framework. In general, EES provision is highly cost-efficient not only for the clients but also for government, because no significant amount of public spending is necessary for EES provision, and ESCOs ensure the savings are as large as possible under the shared saving model. For society as a whole, the benefits of EES provision include avoided energy supply system costs and their external costs, e.g. environmental costs not covered by emission allowances. The revenue of a pure EES provider mainly depends on the revenue of a specific EES project. For energy companies that provide EES, the revenues consist of the avoided cost (e.g. penalties or buyout prices are avoided in countries with energy saving obligations for energy companies), additional revenues, and maybe the recovery of lost revenues (i.e. the lost margin, due to EES-induced energy savings, that can be recovered within distribution tariffs). The end-users’ benefits covers the cost saving due to the energy efficiency measures (under shared saving model) and non-monetary benefits such as the increase in comfort (Suerkemper & Irrek 2010 ).

|

|

Energy Efficiency and Demand Side Management Incentive Program

Type: Feed-in-tariff for certified energy savings |

South Africa |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy