The public sector should lead by example. It can, thereby, also create first markets for energy-efficient building concepts and technologies.

a) ‘Lead by example’ programmes in the public sector to ‘deeply’ retrofit existing buildings to very low energy consumption levels and to only build (ultra) low-energy buildings (as public buildings, in social housing, etc.):

In addition to saving energy and reducing public expenditure, such programmes also raise awareness and investor confidence about the benefits of low-energy buildings and retrofits and demonstrate cost-effectiveness. They also directly provide a market to suppliers of energy-efficient buildings and retrofits.

b) Public procurement requiring very energy-efficient building technologies:

The resulting demand volumes can increase market penetration and reduce market prices for these technologies. This, in turn, will lead to these technologies being used more often and eventually becoming the default technology in new construction and retrofit.

The public sector contributes to a country’s energy consumption to a significant extent. It does not only cover office buildings, but also healthcare and educational facilities, police stations and so on. Some countries, such as Singapore, also have a large public housing sector.

Two kinds of public sector programmes exist. Both require a clear commitment and an energy management unit within a public administration.

1) Lead by example programmes

Lead by example programmes should focus on a whole-building approach and should target both, existing and new public buildings. Both should be constructed as or renovated to the standard of (ultra-) low-energy buildings. Legislation or government decisions should stipulate that government agencies must only build (ultra-) low-energy buildings and, after a certain period of time, only occupy energy-efficient buildings, which should be as clearly defined as possible. In addition, the energy management unit will take care of the energy-efficient operation of public buildings, in co-operation with the managers of each facility. For funding and organising their tasks, energy management units can (or should) have a host of policy tools at their disposal: energy efficiency budgets, third-party financing and energy performance contracting, public internal performance contracting (PICO), sharing savings with departments, as well as the opportunity to bring energy efficiency to outsourcing. It is also advisable to explore possible links between energy efficiency and public administration reform (Borg et al. 2003).

Lead by example programmes also raise the awareness of the construction sector for highly energy-efficient buildings. The construction sector will focus on such buildings and it can gain expertise, in particular, over international competitors. Suppliers of energy-efficient building components will be given a market to sell their products. The private sector is likely to follow the government’s lead for three reasons. Firstly, while energy-efficient buildings have higher upfront costs, they have lower running costs. The government demonstrates that (ultra) low-energy buildings can be cost-effective addressing a core concern of the private sector regarding energy-efficient buildings. Note that government agencies must consider their expenses carefully not wasting taxpayer’s money. Secondly, increasing expertise in the construction sector (due to experience through building and refurbishing government buildings) will further decrease costs for such buildings. Thirdly, private investors in office buildings may be interested in attracting government agencies to occupy their buildings.

2) Energy-efficient procurement schemes

In addition to lead by example programmes focusing on having government agencies occupy only energy-efficient buildings, energy-efficient procurement schemes require agencies to only purchase energy-efficient building components (e.g. boilers). Energy-efficient procurement of building technologies is likely to create an entry market for manufacturers of highly energy-efficient technologies and demonstrate cost-effectiveness to other sectors. This, in turn, will lead to these technologies being used more often and eventually becoming the default technology in new construction (Mäkinen & Neij 2010, p. 5).

As a large number of people in almost every country are employed by the public sector, they may also become interested in living in energy-efficient buildings.

A roadmap stipulating, for example, how many buildings, and public buildings, in particular, are to undergo (deep) retrofits or have energy-inefficient appliances substituted, give further planning security to technology manufacturers and the construction sector.

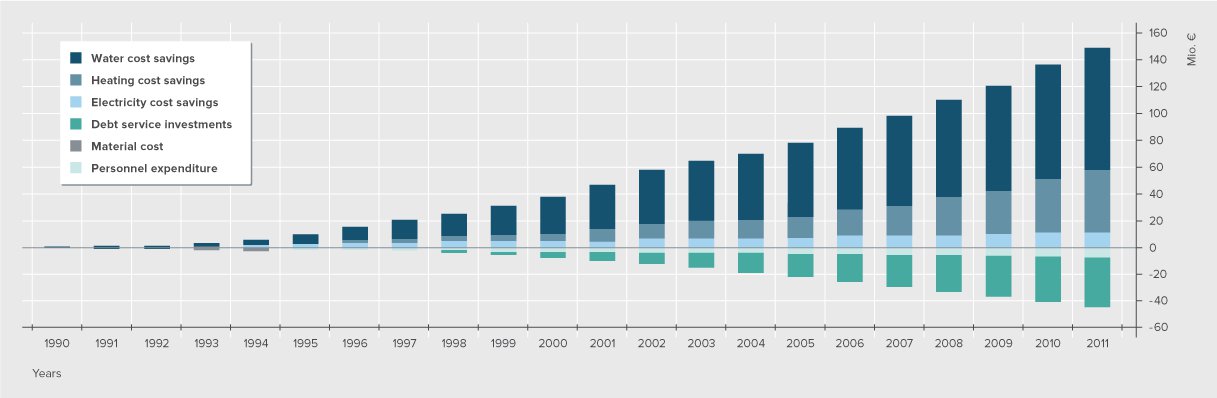

In many places, the bigger challenge is improving the energy efficiency of the existing public building stock. It is highly advisable to favour deep retrofits over small-scale refurbishments, in order to reap even higher energy bill cost savings, Many local authorities around the World have been especially active in this respect. For example, many German cities have reduced the heating energy consumption of their public buildings by up to 50 % since the 1980ies through consequent energy management and energy efficiency investment (Borg et al. 2003). This has been highly cost-effective.

The Congress of the United States and the President of the USA have created the Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) and set an overall target for reducing the energy consumption in federal buildings by 30% in 2015 compared to 2003 levels (The United States Congress NA, Section 8253). By 2009, the intermediate target of 12 % savings had already been achieved, which was over and above target.

The European Union has recently decided that the central governments of its member states must (from 2014 onwards) renovate at least 3 per cent of their building stock floor area each year to improve energy efficiency (Energy Efficiency Directive 2012, Article 5). How this is achieved, is up to the member state governments.

Developing countries (DCs) may find valuable support in international donor agencies, which can help financing higher upfront costs for energy-efficient buildings or building technologies. In particular in DCs, underdeveloped construction and manufacturing sectors are one of the key barriers. Nevertheless, such programmes can have a substantial impact on a developing country’s budget, energy dependence etc. (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2012).

With regard to implementation, a key challenge will be to enable government staff to identify adequate energy-efficient buildings and technologies. An energy agency may help to develop building and purchasing energy efficiency requirements and guidelines, and information material, also functioning as a direct contact for further in-depth information. Easily accessible and comprehensible information and procurement guidelines will increase compliance. Special funding and financing schemes may also be required.

Energy-efficient public procurement also applies to appliances. More information can be found in the appliances section of the bigEE policy guide.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

Lead-by-example and public procurement programmes focusing on very energy-efficient renovation and new buildings and building-related technologies, respectively, have two major aims: 1) reducing energy bills for the public budgets and 2) introducing, accelerating and/or expanding the market for these energy-efficient buildings or technologies.

Due to increased demand from the public sector, builders and manufacturers may drive down costs for energy-saving technologies, which can positively influence the uptake rate of such measures in other sectors (e.g. non-public office spaces, residential buildings etc.).

Worldwide implementation status

A broad range of lead-by-example initiatives and public procurement programmes exist worldwide, most of which were introduced in more developed countries. However, in less developed countries with a less developed industrial sector and low levels of energy access, the public sector can have a large share on a country’s overall energy consumption (e.g. Sub-Saharan African countries). Energy-efficient lead-by-example and procurement programmes are (or should be) cost-effective in order not to stretch the public purse. Nevertheless, such programmes can have a substantial impact on a developing country’s budget, energy dependence etc. (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2012).

Governance level

Lead-by-example programmes can be implemented on every governance level – national, regional, or local, but also international.

Smaller regional or local governments may create joint schemes to be able to manage them.

For multinational implementation, a challenge might be to define (ultra-) low-energy buildings or technologies. However, the worldwide dissemination of the Energy Star, a U.S.-born voluntary energy label functioning in several world regions as a procurement standard, shows that transnational action is possible.

Moreover, several member states within the European Union combined efforts and together successfully created an entry market for high-efficiency circulator pumps through the Energy+ pumps project (Thomas&Barthel 2009; Mäkinen & Neij 2010, p. 32).

Passive options

Public sector programmes should target virtually all actions to improve energy efficiency in public buildings. Obviously, site, microclimate, building form, and building orientation can only be influenced in new build.

For appliances, please refer to the bigEE file on Energy efficient public procurement in the appliances section of the Policy Guide.

In principle, all kinds of actors on the supply side who are able to provide energy-efficient buildings will see an increased demand for the products and services.

Public sector programmes will work best if they interact with other measures of a policy package attempting to increase the energy efficiency in the building sector.

Firstly, a roadmap for the mid-term and the long-term with regard to the building sector gives several actors in the construction sector planning and investment security. A target can for example be to green 80% of a country’s building stock by 2050, including public buildings, as adopted in Singapore. Additionally, governments may require a particular number of buildings or governmental buildings, in particular, to have deep renovation/retrofits every year to approach (ultra) low-energy buildings (e.g. 3% of the building stock, as recently decided in the European Union, however not specifying the energy efficiency level). The target may also relate to new public buildings, such as the European Union’s decision to only allow nearly Zero Energy Buildings in the public sector from January 2019 onwards (and two years later for all new buildings).

Building Energy Performance Certificates and equipment energy labelling will help government staff to identify energy-efficient buildings or building-related technologies. Otherwise the selection of appropriate buildings and products may be very time-consuming, increasing transaction costs substantially. Easy to use life-cycle cost rules are also important. Legislation may need to specify that the most economic offer to select is the one with the lowest life-cycle costs. New buildings should have stricter energy efficiency requirements because measures can often be implemented with a higher cost effectiveness than in renovation.

Special energy efficiency budgets are also important to finance energy-efficient buildings, renovations, or equipment, as these normally show higher upfront costs. Financial support and financing schemes from the central government to regional and local authorities may also help the staff from these governments to fund their programmes. Such support can also be utilised to finance a comprehensive energy audit. Building energy efficiency experts, who are ideally state-certified, may help government staff to identify the most cost-effective solutions (based on Life Cycle Cost analysis), going beyond minimum energy performance standards set by the legislation and, thus, catalysing very energy-efficient ‘deep’ renovation/retrofits and Ultra-Low-Energy new buildings, resulting in even greater energy savings.

ESCOs or public or private energy companies can also help to finance and manage energy efficiency investments. Such companies can help, among other things, designing an energy efficiency project, installing thermal insulation, shading, or other energy-efficient equipment, and verifying the energy savings of a project. Companies must guarantee energy savings. These cost savings, in turn, guarantee the company’s payment. Public Internal Performance Contracting is a variant particularly suitable for smaller investments. Here, the energy management division of the public administration receives a seed funding for an internal revolving fund for energy efficiency.

With regard to particular technologies included in every public building (e.g. boilers, air conditioners, circulator pumps), it can be appropriate to announce a competition for manufacturers of respective technologies. The prize could be, that government authorities guarantee procuring a large amount of winning products. An example of such a competition is the one realised as part of the Energy+ Pumps project for energy-efficient circulators (Thomas&Barthel 2009).

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement Public sector programmes:

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

A central energy agency should be assigned the function of a national public sector energy efficiency information centre. Its tasks should include (Borg et al. 2003):

• Development of guidelines, specifications and LCC methods.

• Developing methods and standard practices for energy management and energy-efficient procurement.

• Dissemination on the national level

• Education and training for public procurement agents and energy managers

• Development of public energy management and energy-efficient procurement tools

• Service and assistance to public energy managers and procurement agents

• Organisation of the dialogue with national representatives and stakeholders

In addition, the national public sector energy efficiency information centre may collect data with regard to public sector programmes. Data should include energy consumption before and after public sector programmes are carried out.

In addition, however, individual agencies should be enabled to implement such programmes.

Funding

High upfront costs or high rents for energy-efficient buildings and energy-efficient refurbishments, in general, amortise only after a number of years. In order to finance these costs additional funding or new funding schemes are necessary. These could be Energy efficiency budgets, public internal performance contracting (PICO), sharing savings with departments, as well as the opportunity to bring energy efficiency to outsourcing. It is also advisable to explore possible links between energy efficiency and public administration reform (Borg et al. 2003).

For refurbishments, in particular, ESCOs could be contracted. In general, a contract between an ESCO and a client includes targeted energy savings. The ESCO will be paid by the cost savings resulting from ESCO’s refurbishments.

Developing countries can gain support from international donors and via the Clean Development Mechanism.

Test procedures

As stated earlier, a system should be in place that makes energy consumption by buildings transparent. If such a system has not been developed, government officials can seek international collaboration. There are several building labels available, e.g. mandatory EPCs in Germany/the EU or the voluntary Green Mark Scheme in Singapore. Whether these schemes can be copied to the respective national context or need modification, needs to be carefully assessed.

At first, a central energy agency should be assigned the function of a national public sector energy efficiency information centre.

For preparation of the lead-by-example and energy-efficient procurement programme, stakeholders should be identified and brought together. Stakeholders are representatives from the national and local governments, from construction and manufacturing industries, from associations of installation contractors and research institutions. The latter could be assigned with conducting a pre-study and calculation of costs, energy savings and cost savings potential.

The public sector comprises a broad range of buildings that need tailor-made energy efficiency improvements. In order for an ex-ante assessment to be valid, it should be made clear, which kinds of buildings will be subject to support from the programme and to future legislation. Thus, it is indispensable to figure out which kinds of buildings consume most of the public sector’s energy or include the highest energy saving potential.

In addition, each administration needs to assign an internal energy management unit. Its first task is to take stock of its buildings and their energy consumption. A benchmark between different buildings of a kind can help identify ‘hot spots’ of buildings that consume more than average and also have a high absolute consumption. These should be priority targets for energy-efficient renovation.

The number of buildings or sub-sectors (educational and healthcare facilities, office buildings etc.) selected is also dependant on the funding schemes. Is it possible to allocate (a large amount of) taxpayer money to public sector programmes or is energy performance contracting a more robust solution with regard to the budget?

Careful consideration is necessary on how government staff are able to identify adequate buildings or technologies. Energy performance certificates (EPC) for buildings and energy labels for technologies can help reduce transaction costs but such measures may not be implemented everywhere. Measures should start simultaneously or before public sector programmes. It may be advisable to draw on international established EPCs or technology labels. Based on such EPC and labels or other information, all governments need to decide on energy efficiency requirements for new buildings, renovation/retrofit and equipment, best with the assistance of the national public sector energy efficiency information centre.

Although one idea behind public sector programmes is to have other sectors follow the public sector lead, discussions with the private sector from the start may yield additional benefits.

Finally, the activities and their results need to be monitored and documented to the public, to show public sector leadership and induce others to follow suit.

Quantified target

The policy can and should have quantified targets. For example, governments can determine (based on research) the number or a percentage of public buildings that will undergo an energy-efficient refurbishment every year, such as the 3 % target for central government buildings in the European Union. The target can also be set as a percentage reduction of total government energy consumption, such as the 30 % savings target by the Federal government of the USA. And it can specify a minimum energy performance standard for public buildings, as the European Union’s nearly Zero Energy Building requirement from 2019.

International co-operation

Governments that are not familiar with public sector programmes to promote energy efficiency in public buildings should seek consultation with researchers and policy-makers from countries that have already established such measures. Through consultations pre-conditions can be identified e.g. life-cycle cost calculation methods, energy management schemes, energy performance certificates, policy design(s) discussed and bad practices avoided.

Developing countries may draw on donor agencies or the Clean Development Mechanism to finance management of the programme as well as higher upfront costs for energy-efficient buildings and building technologies.

Monitoring

For both, new and existing buildings the cornerstone of the monitoring process is energy consumption data and costs for energy-efficiency improvements. In each public sector building, a staff member should be made responsible for delivering information such as monthly energy consumption per m2, monthly energy consumption before the improvement was made, etc., to the energy management unit of the respective local or central government. These energy management units should also collect the costs for and type of energy efficiency improvements (if relevant) for their own activity and success reports, but also report to a central agency e.g. the national public sector energy efficiency information centre we propose, that is collecting and processing the relevant data for the public sector as a whole.

Data on energy consumption per m2 might be even more useful if legislation requires government organisation occupying buildings that can not be refurbished cost-effectively to move into more efficient buildings. Note that net metering is highly important in order to gather precise information with regard to energy savings.

Evaluation

The central information gathering body e.g. the national energy agency or the national public sector energy efficiency information centre, can evaluate the policy and the degree of energy savings, economic benefits and costs depending on the measure(s) undertaken.

Apart from this, it might be worthwhile to gather information on positive or negative side effects. For example, new triple-glazed windows may also reduce the noise-level from outside contributing to a more suitable work-atmosphere.

If data can be collected to increase the knowledge regarding policy dynamics and further side effects (e.g. dynamic market transformation, avoiding lost opportunities and so on) it would prove the evaluation even more important.

Design for sustainability aspects

The policy design of public sector programmes in new and existing buildings could facilitate co-benefits by requiring government staff to also consider factors such as resource efficiency or health aspects. In new buildings, for example, natural lighting elements should be considered, which has been shown to positively contribute to the working environment and productivity. Avoiding harmful substances is another sustainability aspect that deserves attention.

Co-benefits

A public energy efficiency programme can also have a positive impact on the labour market. In particular, the construction sector and manufacturers of energy-efficient technologies as well as installation contractors will feel an increased demand from public authorities.

New technologies may affect the working environment positively. For example, triple glazed windows decrease the noise-level from outside.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers

Many public administrations and authorities have achieved high energy savings in their public buildings, sometimes up to 50 %. For example, many German cities have reduced the heating energy consumption of their public buildings by up to 50 % since the 1980ies through consequent energy management and energy efficiency investment (Borg et al. 2003). This has been highly cost-effective. Some have also achieved high savings in electricity, despite growing use of office equipment.

The Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) in the USA has overachieved on the intermediate target of 12 % savings between 2003 and 2009 . Existing buildings should lower energy consumption by 3% each year harvesting 30% energy savings in 2015 in comparison with 2003.

“Studies of office buildings in the EU indicate 30% savings potential in energy use” (Mäkinen & Neij 2010, p. 7).

In Russia, the government together with the Global Environmental Facility and other international actors targeted energy savings in eleven educational facilities (three universities, eight schools). Investments resulted in over 30% in energy savings.

In 2006, the UK government launched the Sustainable Operations on the Government Estate (SOGE) framework introducing sustainability targets and mechanisms for the public buildings sector. In particular in 2010, the new government announced that the central government administration would become the “greenest government ever”. 3,000 government office buildings were asked to rationalise their energy consumption in order to decrease CO2 emissions by 10% within 12 months. Among other things, energy-efficient technologies were installed or behavioural changes among the staff were fostered. The government achieved a 13.8% GHG emission reduction (or 104,523 tonnes of CO2) exceeding the target and realising energy savings of 238 million KWh. Due to its success, the government set new, more ambitious goals. For 2014/15 GHG emissions are to be reduced by 25% against the 2009/10 baseline (Mure 2011; Government of the UK NA).

Between 2007 and 2013, the Danish government entered into voluntary Curve Breaker Agreements with public authorities, which on average saved 7.5 per cent of electricity by 2011 (see the bigEE good practice policy example).

It is difficult, however, to give generalizable figures with regard to energy savings, costs, and cost savings due to public sector programmes. Among other things, that is because the share of building categories (e.g. public housing, offices, schools) can vary to a substantial degree from country to country. Other factors such as climatic conditions, interrelated or conflicting policies (e.g. fuel subsidies) need to be factored.

Costs for the policy will be dominated by the investment in energy-efficient buildings and renovation. Some examples include:

The government of NSW has allocated AU$ 6.4 million of taxpayer money to retrofit 150 NSW-government buildings (Government of NSW 2012).

The collaboration between the Russian government and international actors allocated more than USD 1 million in order to make eleven schools energy-efficient.

The UK’s initiative to reduce carbon emissions by 10% within twelve months was supported by the Low Carbon Technology Programme (LCTP) which was funded with £14 million between 2009 to 2011. Funds were used to finance 44 carbon-cutting projects in 15 central government departments (Mure 2011; Government of the UK NA).

Since 2007, Germany’s KfW Bank has introduced financial support schemes for social infrastructure facilities, such as schools or kindergartens. Between 2007 and 2010, 971 applications were accepted. €365 million in loans were given to these facilities. All in all, the volume of investments (also including those not facilitated by the KfW and/or not related to energy efficiency) was around € 625 million (Clausnitzer et al. 2011).

The United States’ Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) has been supporting federal agencies with meeting energy efficiency (and water conservation) targets since 1973 (Harris & Shearer 2006). One of these targets is the reduction of energy consumption per gross square foot of federal buildings between 2006 and 2015 by 30% (as compared to 2003) (FEMP 2010). For 2014, the FEMP has requested $ 36 million (Department of Energy 2013, p. 7).

Investment in energy efficiency in public buildings through public sector programmes is often highly cost-effective. A study estimated that the payback time does not exceed three to five years (Mäkinen & Neij 2010, p. 28). Even for the very energy-efficient Passive Houses the City of Frankfurt am Main builds as their standard, payback times are between five and fifteen years (see the bigEE good practice policy example). Energy management units in German cities often save three to five times their staff costs through optimised control and operation of public buildings alone (Borg et al. 2003).

Further examples may back these findings:

The NSW government estimates that small-scale refurbishment actions will result in annual electricity bill savings of AU$ 5.8 million. With funding of AU$ 6.4 million, the payback period is highly attractive, in particular against the backdrop of limited public budgets. Unfortunately, further information on opportunities lost, because of the initiatives focus on small-scale measures, have not been available. The NSW government also hopes to motivate private households to replicate respective small-scale building upgrades (Government of NSW 2012).

While information regarding the specific costs of UK’s 10%-initiative were not available, it has been successful in saving £13 million annually in energy bills (Mure 2011; Government of the UK NA). Conservative evaluations estimate that through KfWs’ programmes to increase the energy efficiency in public sector buildings, within a period of 30 years, energy savings will amount to €660 million – only taking into account the 971 cases supported between 2007 and 2010. Thus, within this period the energy savings pay back for the full investments, including both renovation needed anyway and the improvement of energy efficiency. The evaluation report notes that the payback time depends on a building’s actually implemented energy efficiency improvement (Clausnitzer et al. 2011).

The FEMP is considered to be one of many contributing factors that helped federal agencies in the USA to reduce their energy consumption. Harris & Shearer (2006, p. 49) found that “[b]etween 1985 and 2004, Federal agencies reduced their facility energy consumption by 25.6%“. During that period the annual energy bill of federal facilities almost halved from US$ 6.1 billion to US$3.7 billion.

The city of Montpellier in France’s energy policy has been effective since 1979. By 2000, the city saved €1.8 billion due to the policy. It is estimated that “electricity expenses for municipal buildings being half as high as for comparable cities” (Borg & Co AB et al. 2003, p. 39). The Energy Department of the City “centralises the annual energy invoices (but informs each facility responsible), establishes technical specifications (e.g. lighting, double glazing) for all city buildings, participates in the selection of architects for new building constructions, [and] communicates on these activities” (ibid.).

|

|

Passive House Standard for Municipally Owned and Municipally Used Buildings in Frankfurt am Main

Type: Public sector programmes |

Germany |

|

|

Curve Breaker Agreement

Type: Voluntary Agreements with commercial or public organisations |

Denmark |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy