The traditional way is that integrated energy efficiency programmes with financial incentives, information and individual advice are managed by existing government agencies and funded from the public budget. The advantage over other mechanisms is the direct implementation and budget control by government and parliament. Experience shows, however, that (1) appropriations for programmes in the government’s budget are more subject to cuts and fluctuations or even “stop and go” effects than energy efficiency funds created via special levies or than targets under energy efficiency obligations and that (2) government agencies are often less flexible than energy efficiency funds and trusts or energy companies in the measures they can take to support consumers and market actors.

Energy efficiency programmes funded by public budget are among the most prevalent policy instruments around the world. They can include and integrate some or all of information, individual advice, financial incentives, financing, training, and research, development and demonstration. Financial incentive programmes aim, especially, to overcome the barrier of high upfront costs for taking up energy efficiency technologies that involve high investment and long payback time (UNEP 2007; Rezessy & Bertoldi 2010). At the same time, they also send a clear signal to market actors about which technologies are promoted by the government in the near term.

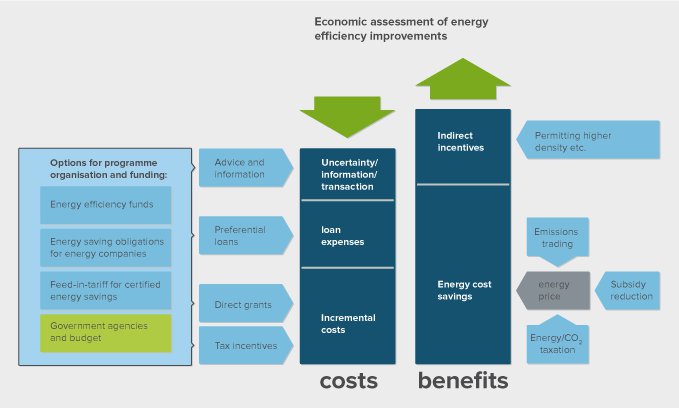

The graph shows how government agencies and budget enable the implementation of different types of energy efficiency programmes that reduce costs and barriers for energy efficiency improvements.

However, government-funded programmes often run over a limited period and or focus on a narrow range of energy efficiency measures and sometimes on offers to a specific societal group.

In addition, the implementation of publicly-funded programmes faces some challenges and needs careful design. Experience shows that appropriations for programmes in the government’s budget are more likely to be subject to cuts and fluctuations than energy efficiency funds created via special levies, or targets under energy efficiency obligations. Thus, the institutional arrangements for publicly-funded programmes including the range of activities to pursue and sufficient budgetary provisions should be mandated and secured by legislation.

Furthermore, government agencies are often less flexible than Energy efficiency funds and trusts or energy companies in the measures they can take to support consumers and market actors. There is a need to work through local agents such as energy consultants, banks, consumer advice centres or chambers of commerce. They all need training on the programme and the right incentives to promote the programmes, and are thus a limiting factor to quick programme adaptations. Also, application and approval processes in government programmes tend to be more rigid than for programmes operated by Energy efficiency funds and trusts or energy companies.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

Publicly-funded programmes aim to overcome the barriers for energy efficiency that market actors face and to strengthen their incentives. The programmes should therefore include and integrate all the sector-specific policies and measures, particularly information, individual advice, financial incentives, financing, training, and research, development and demonstration.

Worldwide implementation status

They have already been widely implemented around the world. Examples of financial incentive programmes are shown in Austria, where the federal and state government launched the “Federal Promotion of extraordinary efficiency buildings” for residential buildings to reach 65 kWh/m2 in 2006 and 25-45 kWh/m2 from 2010, with a total budget of 1.78 billion euro over a four-year period (BPIE); and the Czech Republic, where in 2009 with an annual budget of 61 million euro, the government started the Green Savings programme that supports heating installations and the utilisation of renewable energy in reconstructions and new buildings (Zelena Usporam).

The Green Savings programme, Czech Republic

From the sale of emission credits the government of the Czech Republic has allocated funding for energy efficiency investments in new and existing buildings.

www.bigee.net/s/9xxh5p

Espaces Info Energie (EIE) – Local Energy Information Centres, France

250 Local Energy Information Centres, located throughout France, give tailor-made advice on energy efficiency in buildings. The residential sector is the core target group. The network is co-funded by ADEME, the French Environment and Energy Management Agency, and local and regional authorities.

Governance level

Budget-funded programmes can be implemented at national, trans-national, regional or local level.

Publicly-funded programmes can cover the residential, industrial, commercial or public sector.

Publicly-funded programmes can support the market introduction or breakthough in the most energy-efficient building concepts, technologies, and management/behaviour in all sectors and end uses of energy.

For example:

Low-energy buildings, Ultra-low energy buildings, Zero or Plus energy buildings

Thermal Comfort, Building Envelope, Passive Cooling, Passive Heating, Mechanical Ventilation, Cooling, Heating, Domestic Hot Water, Lighting, Vertical Transportation, Building Integrated Power Generation, User Behaviour, Building Energy Management

Depending on the scope of the publicly-funded programme, it can address actors on both the supply side and the demand side, and those who are specialised in end-use energy efficiency improvement actions. They include

As the programmes usually combine information and financial incentives or financing, in most cases the direct beneficiaries will be investors and users of energy-efficient buildings.

The indirect beneficiaries of government programmes are numerous and vary depending on the supported programmes. Actors on the supply sideespecially benefit indirectly because they can acquire jobs and gain experience.

Barriers addressed by governments through their programmes can be related to the market risk for suppliers and to a lack of information, motivation and financing on the investor side.

Other policies, such as Minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) and Mandatory comparative energy labels or Energy performance certificates, or RD&D funding can provide an important basis for deciding which programmes/ measures to promote. Programmes should target solutions that exceed MEPS in energy efficiency by far, such as ultra-low energy buildings. They can thus prepare the next revision of MEPS.

Funding

The government’s budget needs to have sufficient resources allocated to the various programmes.

Test procedures

The programmes will normally rely on test procedures generated, e.g. in the preparation of MEPS and energy labels but not develop own specific test procedures for energy efficiency.

Others

The government agencies in charge of programme development and implementation need highly qualified staff with knowledge of energy efficiency solutions and potentials as well as programme design, implementation, and evaluation.

These will depend on the type of programme to be implemented. For instance, for a financial incentive programme the main funding areas, the rules (including eligibilities and energy efficiency requirements) and procedures, and the level of the financial incentives should be determined at the outset. In addition, a comprehensive cost and market assessment is essential for developing an appropriate level of funding and financial incentives. Furthermore, to ensure the effectiveness of the programme, the interactions with other policy instruments also need to be planned and communicated. Finally, monitoring and evaluation should be in place.

Quantified target

Although a publicly-funded programme does not need a quantified target, such as the amount of energy saved per year or number of participants, we recommend it. It may have a fixed amount of budget within a certain time period.

Co-operation of countries

International co-operations that share best practices of the design and implementation of programmes funded by public budgets and implemented by government agencies can help policy-makers at national, regional/local level to improve their policies.

Monitoring

Monitoring and reporting procedures need to be specified in the description of the publicly-funded programme.

For evaluation of energy savings from the programmes, the documentation should cover the number of participants or beneficiaries, the energy efficiency actions they have taken (e.g., purchase of energy-efficient buildings or refrigerators), and the unitary gross energy savings achieved by each action (either via agreed deemed savings or ex ante agreed calculations, or via ex-post evaluations). To ensure sufficient and useful monitoring and evaluation data can be provided from the programmes, the provision of this data should be part of the funding requirements to programme beneficiaries.

For evaluating economic benefits and costs, implementing agencies need to separately monitor their costs incurred, for programme design, administration, communication and evaluation costs and for any financial incentives. They should also monitor the incremental part of the energy or power (kW) prices that the participants/beneficiaries would have paid for the energy or power they saved. Furthermore, incremental costs incurred by the customers to invest in energy efficiency or operate their premises and equipment in an energy-efficient way need to be estimated via market monitoring or ex-post evaluation.

Evaluation

In order to be credible, evaluation should be done by independent institutes or consultants and not by the government agencies themselves.

The possibilities and formulas for evaluating energy savings will depend on the type of energy efficiency action supported as well as the type of energy efficiency programme (e.g., information only programmes are more difficult to evaluate than financial incentive programmes, see our detailed files on these types of policies and measures). The same holds for economic benefits and costs from either the customer/participant perspective or that of the national economy/society.

In addition to the data directly monitored for the energy efficiency programmes, evaluation of net energy savings compared to baseline trends should address side-effects such as rebound, multiplier, and free-rider effects, and the ‘lifetime’ and potential deterioration of energy savings.

For the economic benefits from the perspective of the national economy/society, standard values for the incremental energy supply costs that will be avoided in the long run for a kWh of energy or a kW of load should be developed by the government.

Sustainability aspects

Publicly-funded energy efficiency programmes can be designed to promote sustainability aspects, such as resource efficiency, by including these aspects in their scope, e.g. for advice and grants.

Co-benefits

The increasing demand of granted energy efficiency products creates job opportunities in these fields. In addition, when a publicly-funded programme targets social groups having low income and low chance to obtain credits, it also addresses the social sustainability.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy:

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers:

The costs of an energy efficiency programme depend highly on the programme setting. For instance, the overall allocation of the Green Saving programme in the Czech Republic is up to 25 billion Czech crowns (around EUR 1 billion).

In the German KfW programme, in 2010 the programme provided €4.9 billion (loan option) and €100 million (grant option) to investors for building refurbishment. The government supported these programmes and another programme for energy-efficient new buildings that provided €3.7 billion with budget allocations of €1.4 billion.

In Mexico, total investment for eco-technologies supported by the Green Mortgage in the year 2009 is estimated to have been in the range of € 190 million.

The “This is your home grant” financed in combination with the Green Mortgage in the same period was about € 166 million.In France, ADEME funds the EIE substantially (the cost estimation ranges from €5 million per year to €10.5 million per year).

With proper design and implementation, programmes operated by government agencies and funded from the public budget can be highly cost-effective for society, beneficiaries and even for the government’s budget.

For example, in Germany, the heating costs saved by the KfW programmes amounted to ca. €250 million per year for the 2010 programme year. The programmes are cost-effective to consumers and even for the government budget. According to estimations, together, the new build and refurbishment programmes result in about €6.3 billion of tax revenues, as compared to €0.9 billion of budget allocation to the programmes. However, this is based on the full cost of construction, not just the incremental costs of energy efficiency improvements. In addition, employment effects from the 2010 refurbishment programme year add up to about 92,500 person years.

The medium repayment period for measures financed under Mexico’s Green Mortgage in 2010 was calculated to be 4.1 years. With an assumed medium lifetime of 10 years for all measures (and no maintenance costs considered), the net benefit for the housing owner would be about € 900.The French EIE triggered substantial investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy measures. For instance, the leveraged investment was €465 million Euro in 2008.

Try the following external libraries:

| Energy Efficiency Policy Database of the IEA |

| The Building Energy Efficiency Policies database (BEEP) |

| Clean Energy Info Portal - reegle |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy