Competitions for energy efficiency awards promote the development and commercialisation of new appliances that are more energy-efficient than the best available technologies (BAT). Simultaneously, through awareness raising channels, the award scheme will draw the public’s attention towards energy-efficient appliances. Manufacturers and investors in energy-efficient appliances can benefit both financially and in terms of improved reputation and prestige.

Many countries have already organised competitions and awards to promote the best practices in energy-efficient appliances. At times, improvements in energy efficiency over pre-existing BAT of 25 to 50% have been achieved.

The core goal of a competition and awards programme is to make appliance manufacturers engage in R&D and/or sales competition reaching out for the (new) most energy efficient appliance of a particular appliance category. In the long run, such a measure may result in a push for market transformation, especially if a large share of appliance suppliers participate in the competition.

In order to reach out to most of the suppliers, it is necessary to set the incentives correctly. Apart from the actual award (which is likely to be a cash award and may cover a part of the investments in development, start-up of production, and commercialisation), indirect incentives resulting from winning the contest might be as or even more important. The reputation effect especially is a vital incentive. That is also why a promotion or awareness raising campaign is very important because the company can also make use of the award for marketing purposes.

Large quantity purchasers can be addressed by an agency or similar organisation in charge of organising the contest. These purchasers e.g. public authorities, can commit themselves to buying a particular quota of the winning product. This would move the competition and award scheme towards the policy type of technology procurement (cf. the bigEE dossier on Co-operative procurement). Another part of the competition and award package can be a logo indicating the winning product.

From the very beginning, the agency responsible should involve all the relevant stakeholders (manufacturers, research institutes, NGOs and even retailers) in order to increase acceptance of the award. A goal should be formulated; e.g. increasing the energy efficiency by at least 40% as compared to the minimum energy performance standard (MEPS). If the award scheme is designed by a governmental or government-affiliated agency, it is, ultimately, tax payer money used to fund organisation, administration and the final prize. Marketing experts can help to gain substantial public awareness.

Many countries implemented awards and competition schemes to “continuously search, benchmark and acknowledge initiatives and best practices in energy efficiency” (Manan et al. 2010). An outstanding example of the successful implementation of an award scheme was the SERP programme: In 1993/94 the U.S. Department of Energy and 24 energy companies launched the Super Efficient Refrigerator Programme (SERP). The winner received USD30 million for achieving an energy efficiency improvement of 25-50% as compared to the1993 MEPS. For 1994, it was estimated that 25,000 of these highly efficient refrigerators were sold and equated to 7.1 GWh/yr of energy savings. Cumulatively, 250,000 of these appliances entering the market were estimated to save 96 GWh annually. Market transformation effects led to additional positive impacts (Ecomotion 1994). The energy efficiency levels demonstrated by SERP facilitated the 2001 revision of refrigerator and freezer MEPS in the USA.

NOTE: Often, the term award is used as another word for a voluntary energy label or sometimes a financial incentive for energy-efficient products or for manufacturers or retailers engaging in the production and sale of energy-efficient products exceeding a certain energy performance (best available technologies—BAT). This is not the kind of awards we wish to cover here. Instead, our focus here is on awards for the development and commercialisation of new appliances that are more energy-efficient than the (previously existing) BAT.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

A competition and awards programme can serve as the first action in order to transform the market: the main aim is to make manufacturers invest in development, start-up of production, and commercialisation of new appliances that are more energy-efficient than the (previously existing) BAT. Further aims are to increase the competition among manufacturers as well as to draw consumer attention to energy-efficient appliances.

Worldwide implementation status

Competition and award schemes were implemented in several countries. Such programmes have a long history in Japan and in the USA. A well-known measure is the Energy Star programme that promotes very energy efficient appliances with an award; for example. But also there are other countries which have already introduced this type of policy (Zhou et al. 2012). Other programmes can be found for example in Europe and China.

In 1993/1994, the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) and 24 energy companies launched the Super Efficient Refrigerator Programme, which provided USD 30 million to the winner (winner takes all approach). Manufacturers’ appliances were to exceed minimum energy performance standards by 25-50%. It had been estimated that 250,000 of these refrigerators gradually entering the market would save 96 GWh annually (Economotion 1994).

Student design teams can apply for the Max Tech and Beyond: Ultra-Low Energy Use Appliance Design Competition organised by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). “DOE is in the process of exploring mechanisms and pilot programs to bring the best ideas to market” (LBNL 2012).

Another programme from the USA is the Energy Star programme. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) introduced several programmes under the name “Energy Star” and avoided with all these programmes 170 MTCO2 eq of greenhouse gas emissions in 2010. One of these Energy Star programmes is an award scheme, which started in 1993. The EPA awards manufacturers, retailers, energy companies etc. that made outstanding contributions to promote Energy Star labelled products. Categories are: Partner of the Year, Award for Excellence and Award for Sustained Excellence. To push the industry to produce energy efficient products two additional awards were introduced: The Most Efficient product designation and the Emerging Technology Award (Zhou et al. 2012).

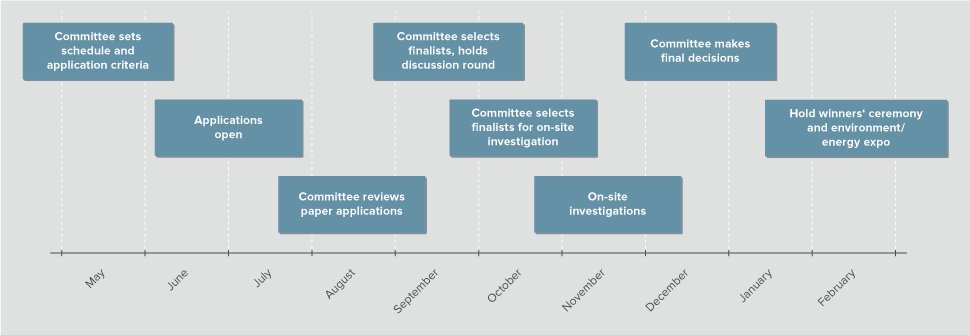

Japan introduced an award scheme in 1948. Today a different scheme called the Energy Conservation Grand Prize is in place, which started in 1990. The awards are given out to companies, that reach a specific goal (produce high energy efficient appliances etc.). The responsible actor is the Energy Conservation Center of Japan (ECCJ), under the Japan Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI). The criteria to win a prize are energy efficiency/usage properties (33%), recycling (17%), advanced/innovative technology properties (17%), economic/market appeal properties (17%) and environmental improvement/safety properties. The schedule is shown in the next figure:

Another Japanese programme is the award for retailer promotion of energy efficient appliances. The best stores receive an eShop logo. Some of these stores have the chance to receive one of the following top prizes: the METI Minister’s Prize, the Environmental Minister’s Prize, the Energy and Resource Agency Director’s Prize and the Energy Conservation Centre Japan President’s Prize. The criteria include: the management policies, sales staff knowledge, display and explanation, energy efficiency of the store and the sales of high energy-efficient equipment. The numbers of these top prizes were 6-7 in the earlier year and 2-4 in more recent years due to stricter selection criteria. The programme ended in 2011 (Zhou et al. 2012).

Another example comes from China. The National Lead List of Excellent Enterprises and Energy-saving Products was implemented in 2008. The lists were the following: “Energy efficient company lead list”, “highly efficient product ranking” and “total energy saved product ranking”. The prizes were awarded for room air conditioners, refrigerators, clothes washer, gas-fired water heaters, electric water heaters, computer monitors, self-ballasted compact fluorescent light bulbs, and induction stoves. In 2009, 222 awards were given in total. The responsible organisation, CNIS, publishes an official press release and holds a ceremony for the winners (Zhou et al. 2012).

Governance level

Competitions and awards can be implemented on a national, trans-national, regional and local level. Most of the time the policy was implemented on a national level.

However, the larger the awareness raised through the measure, meaning the more people are addressed, the higher the incentive for manufacturers to engage in the competition. From this perspective, the policy could be implemented on a transnational level. However, it might be advantageous to introduce such a measure in countries with the same MEPS and/or labelling regulation.

The policy can have the objective of improving the energy efficiency for any kind of appliance in all sectors.

A competition or award measure can be used for a very broad range of appliances, for example refrigerators, TVs, washing machines etc. Therefore the scope of appliances that can be covered is unlimited in principle.

The most important aspect of a competition and award programme is the awareness-raising factor. However, increased consumer awareness can only be achieved through media attention. The agency managing the programme must guarantee that sufficient media attention is drawn towards the product receiving the award and the product’s manufacturer. Moreover, the winner should be presented on websites related to the topic of energy efficiency. Apart from ordinary websites, social media platforms can be used to foster awareness, especially if these campaigns also include a contest so that participants can win respective products. Other promotion strategies are newspaper, brochures, invitations, road-shows etc.

A minimum energy performance standard (MEPS) for the appliance category, which is targeted by the competition and an awards programme can be used as a benchmarking tool. A similar function can be attributed to a label (e.g. a mandatory comparative energy label) differentiating between good and bad performing appliances. For instance, the winner can be compared with both, the MEPS and the all-time best-performer, referring to the fact that the awarded appliance/ appliance manufacturer exceeded the MEPS by e.g. 50% or the current BAT by e.g. 25 %. Such a statement emphasises the significance of the achievement(s). The winner’s energy performance can also be taken as the new MEPS after a few years as a transition period.

A logo designed only for the competition and awards programme can increase consumer awareness for the winning appliance and the appliance manufacturer. The more awareness the programme can raise, the more likely it becomes that manufacturers reach for ambitious goals. Alternatively, an indication for the product receiving the award could be integrated in a mandatory or voluntary labelling scheme.

Further incentives could increase the ambition of manufacturers for winning the award and really becoming committed in R&D. For example, monetary prizes might be interesting in order to amortise R&D and commercialisation investments. Moreover, a commitment of large-quantity buyers (public authorities, retailers, hotels, schools) to purchase the winning product increases the incentive for manufacturers due to the pre-existing knowledge of demand.

Financial incentives for purchasing energy efficient appliances might enhance the market penetration of leading appliances. Especially, if financial incentives for award-winning appliances are higher compared to appliances of the same category that are also energy-efficient but less so than the award-winning products.

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement competitions and awards:

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

Various actors can initiate a competition and awards programme. If the measure is to serve a particular policy goal or to be a supplementary measure to other policies, an energy department or a closely affiliated agency should be amongst the key actors.

However, such programmes can also be launched by non-governmental stakeholders such as a business and/or non-profit network.

Furthermore, an expert group needs to be set up for the technical analysis and the analysis of improvement potentials.

Funding

Depending on the status of the responsible agency (governmental or non-governmental), the budget (i.e. the cash prize for the winner and the budget for the organisation and implementation of the programme, including publicity) needs to come from the general budget of the government or from the non-governmental stakeholders.

Test procedures

Test procedures for energy consumption or efficiency are needed to define the criteria for the selection of winners in a transparent way. At best, test procedures developed for an existing national regulation (like MEPS or energy labels) can be used, and the catalogue of criteria is developed with neutral, scientific institutes.

First and foremost, it is important for the measure to identify which appliance category might have the highest positive effect(s) in terms of energy or cost savings. For example, if findings show that TV sets have rather low energy efficiency as compared to neighbouring countries, an award scheme may be highly beneficial.

Then, the agency should develop a transparent catalogue of criteria, which is necessary for picking winners. It is necessary to clarify which appliance categories are applicable; e.g. refrigerators in general or is the category further differentiated in combinations of refrigerators and freezers, two-door refrigerators etc. Research bodies should be consulted as well as business stakeholders. The latter should be addressed as soon as possible because – depending on the contest design – they need time for the application and innovation process. A deadline needs to be set. Moreover, the award scheme needs to be concretised and the prize should be defined (cash prize, financial incentives for the purchasers of a first series of award-winning appliances, publicity, technical assistance, etc.). After a defined period of time the winner of the award or competition should be selected and made public. A media agency may help launching the awareness campaign.

Ex-ante impact and cost-assessment are desirable. However, the measure is likely to be used as a supplementary initiative to other policies, and attribution of savings to an award competition may then be difficult.

Quantified target

The policy can and should have a quantitative target. The amount of award-winning products that get sold in the first one or two years after the competition—or even during the competition period if a minimum amount of sales is a condition for winning the award—and the energy savings compared to the previous BAT levels are important factors to decide whether the policy was successful or not.

If a special contract with public authorities is signed, which commit themselves to only or predominantly buy the winning product, these official figures can be used as a benchmark.

Depending on the competition design, the amount of manufacturers participating in the contest could also be used in order to indicate success or failure. For example, if a large share of manufacturers participate, it can be considered as a success.

International co-operations

Several countries have already introduced award and competition programmes. Co-operations can be helpful to exchange experience and know-how. Furthermore, it is possible to implement an award competition on transnational level. This can make the policy more effective and create a high demand towards energy-efficient products.

Monitoring

Sales figures, the improvement of BAT levels through the competition, and costs for R&D and commercialisation of the respective products may help evaluating the measure.

An independent research body should monitor and measure the impact of the programme. Important factors are the number of participating manufacturers respectively of the target group, the R&D efforts and the achievements.

Evaluation

The award or competition scheme should be evaluated by independent research institutes or a similar body. The evaluation should include overall energy savings and if possible monetary benefits and costs. Important input factors are the participating actors, the improvement of the targeted technology and the development of the market.

Design for sustainability aspects

Sustainability aspects can be included in the criteria catalogue. The award competition can include sustainability criteria like water or other resource efficiency or health aspects as values for the overall score. The more aspects that are covered, the better the award can be promoted via media channels.

Co-benefits

To a large extent the inclusion of co-benefits will depend on the country-specific context. For example, if many manufacturers are located in the country, which launched the competition or awards scheme, the push for technological improvements may also lead to positive labour market effects.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy

There are some problems, which might arise. Either there are hardly any companies participating in the contest or there are hardly any improvements to the appliance category.

A problem could be that the prize for the winner is not attractive enough resulting in a low participation rate.

Another barrier could be a complex application form, which could hinder companies in participating.

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers

In order to reach out to most manufacturers, it is necessary that the incentives of the award are strong enough. Energy efficiency criteria, on the other hand, should also be demanding enough to ensure sufficient improvement of energy efficiency.

Energy efficiency award competitions have made significant impacts to support energy efficiency and to encourage companies to develop innovative technologies (Manan et al. 2010). However, the potential energy savings vary among projects and the product development.

An example is the SERP programme from the United States: In 1993/94 the U.S. Department of Energy together with 24 energy companies launched the Super Efficient Refrigerator Programme (SERP). “[R]efrigerator manufacturers had three months to develop proposals for R/F [refrigerator/ freezer] prototypes that had automatic defrost, were CFC-free, had the capacity of conventional units, and were at least 25% more efficient than 1993 applicable federal standards” (Eckert 1995: iv). “In terms of direct sales, 25,000 SERP refrigerators are forecast to be sold during 1994 which would provide annual energy and capacity savings of 7.1 GWh and 1.6 MW conservatively […]. When the program’s complement of 250,000 refrigerators enter the market as planned, the program will result in direct annual energy savings of 96 GWh and 22 MW.” (EcoMotion 1994). According to Eckard (1995, p. 19) estimated energy savings are 1,059,800 MWh over 14 years saving USD 82,250,000 in consumers’ bills. However, more energy is to be conserved as other manufacturers also started focussing on energy-efficient appliances.

Expected costs cover the possible financial support, the award for each project and the promotion of the competition.

The question who actually pays for the costs depends on the financial institution who finances the measure. If it is located in a governmental or government-affiliated body, it is likely that, eventually, taxpayers pay for the costs.

The costs for administration and co-ordination might be negligible compared to the incentive scheme necessary to address the large share of all manufacturers. Within the U.S.-American Super Efficient Refrigerator Programme 24 utility companies committed a total amount of USD 30 million to the winner of the award scheme. This was the major share of the programme’s cost.

With regard to the R&D and production start-up investments, there is no information available.

Potential energy savings and expected costs will obviously depend on the competition and award programme. In general, the net benefits should be high with such competitions and awards, given innovations they activate and high spill-over effects.

For example, SERP’s energy savings of 1,059,800 MWh over 14 years are estimated to save USD 82.25 million in consumers’ bills (Eckard 1995, p. 19). This is almost three times the cost of the prize for the winner of the award scheme, which was USD 30 million and was the major share of the programme’s cost.

|

|

Global Efficiency Medal

Type: Competitions and awards |

European Union (EU), United States, Canada, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein, India, Australia |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy