Energy supply and or distribution system operator companies can be mandated by law to save a certain amount of energy in energy end uses (i.e. on the demand side, with their customers) and prove achievement of that target.

The energy companies thus receive both the responsibility and the right of cost recovery for the organisation and funding of energy efficiency programmes. These programmes typically combine information, motivation, financial incentives and or financing, capacity building, and RD&D/BAT promotion. Energy companies can implement such programmes as an alternative to, but also jointly with an energy efficiency fund or trust or the government itself.

A potential but weaker alternative to a legal obligation could be voluntary agreements with energy supply, transmission or distribution companies to achieve a certain amount of energy savings.

The most successful countries achieve gross energy savings equivalent to around 2 % per year and more of the target groups’ energy consumption through energy saving obligations. Up to 1.5% per year of these savings are additional to the baseline trends of energy efficiency. Usually, these energy savings are cost-effective for consumers and society.

Systems that, in addition to setting a savings quota, also allow for market trading of certified savings among obligated actors and/or third parties are termed ‘white certificate’ schemes. Similar to the way in which emissions trading functions, the purpose of the trade component is to ensure that, thanks to the market mechanism, a politically desired quantity of energy savings can be generated at least societal cost. Actors who are able to achieve energy savings at a marginal cost below the certificate price will thus continue to produce certificates beyond their own quota and offer these on the market until their marginal cost is equal to the price. Conversely, companies that are only able to meet their obligation at a higher marginal cost will buy certificates on the market as long as this is cheaper than performing energy efficiency measures themselves. Thus, in such a system, the marginal compliance costs of all obligated parties converge, and the environmental policy goal is attained at least cost.

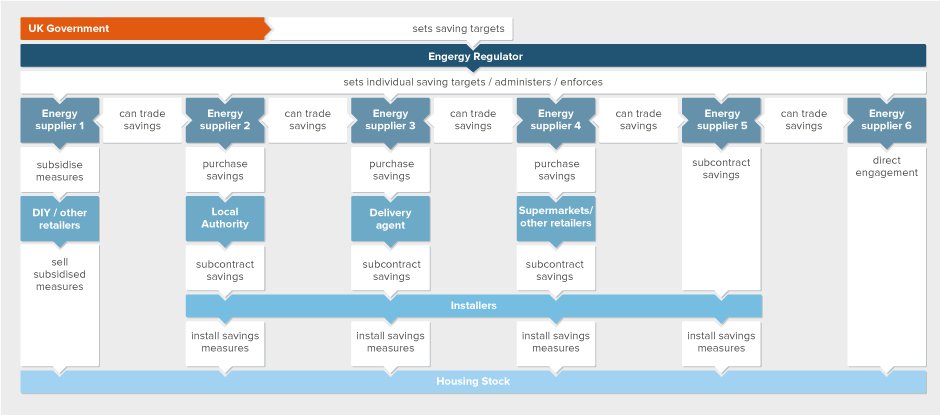

There are many ways of setting up an ESO scheme, regarding target end use sectors, target fuels, obligation of network or supply companies, and other issues. The graph presents the set-up in the United Kingdom and the different ways the obligated supply companies have to address their customers and thereby to meet their targets.

Under an energy saving obligation (ESO) scheme, energy companies (suppliers or distribution system operators) are obligated by law to achieve a politically set volume of energy savings by means of energy end-use efficiency programmes and measures. The energy companies must prove to a competent authority that they have achieved a corresponding quantity of energy savings.

The overall savings target is apportioned among the obligated energy companies according to their respective market shares. In order to avoid competitive distortion, such schemes often only obligate companies above a certain size threshold (in terms of turnover or numbers of customers).

In order to meet the targets imposed upon them, the companies concerned must motivate or support final consumers to carry out concrete energy efficiency measures. In most schemes this is done primarily by way of financial incentive programmes, but some systems also deploy other kinds of measures (e.g. free or subsidised energy audits).

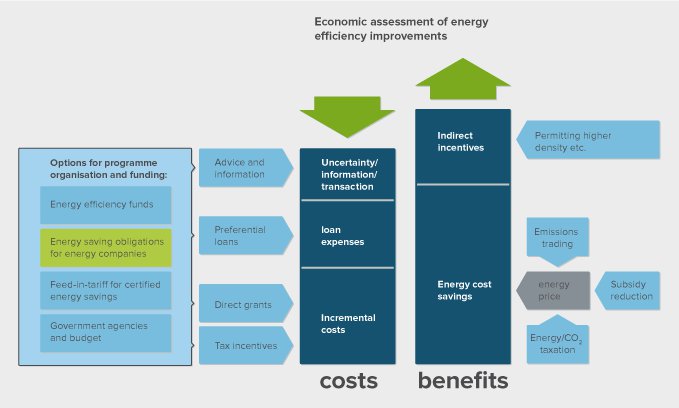

The graph shows how Energy saving obligations for energy companies enable the implementation of different types of energy efficiency programmes that reduce costs and barriers for energy efficiency improvements.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

Energy saving obligations (ESOs) aim at supporting market breakthrough of energy-efficient solutions, which can and should be required to be very energy-efficient. Energy-efficient user behaviour and building operation may also be promoted. This is achieved through energy efficiency programmes that typically combine information, motivation, financial incentives and or financing, and capacity building. These programmes are implemented by energy companies under regulatory oversight in order to fulfil their obligation to save a certain amount of energy each year.

Worldwide implementation status

As it is a still a relatively new policy mechanism – except for the USA, where it has been in place for around 30 years – implementation of ESO schemes is still not widespread. However, the number of countries that have implemented such schemes is growing. ESO schemes (with or without trading of energy savings (‘white certificates’)) are in place in the following countries or federal states: United Kingdom, Denmark, Italy, France, Belgium (Flanders region), Australia (New South Wales, South Australia, Victoria), Canada (Ontario), United States (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Texas, Vermont), China, Korea, Poland (planned) (RAP 2012). The European Union recently passed legislation requiring all Member States to introduce ESO schemes with the target to save 1.5 % of energy each year or alternative policies achieving the same level of savings.

Governance level

All the existing ESO schemes are implemented either at the national or regional/federal state level.

Implementation at local level is not recommended due to high administrative costs and high effort for setting up such a system.

All kinds of energy saving measures in the residential, commercial, industry, and public sectors can be implemented under an ESO scheme. Many of the existing schemes have a focus on the residential sector.

All kinds of energy saving measures can be implemented under an ESO scheme. There is a tendency to favour standardised, easy-to-implement measures such as boiler exchange, installation of CFLs, water saving devices, etc. Consequently the focus is rather on improving existing buildings than on measures for making appliances more energy-efficient.

For the primary target group, i.e. the energy companies, the policy addresses the barrier created by conventional price and market regulation that they earn more by increased energy consumption and there is no recovery of energy efficiency programme costs or no reward for energy savings.

Since energy companies usually assist their customers with energy efficiency programmes, combining information and financial incentives, these programmes mainly address the following barriers:

In general, governments need to assess and decide which energy efficiency potentials and end-use actions they want to address through an Energy saving obligation for energy companies and the corresponding programmes by the energy companies or alternatively through an Energy efficiency or through programmes directly offered and funded by the government. This will also depend on the general performance of energy companies and the regulator.

ESOs and Energy efficiency funds can also be used complementary to each other. For example, the fund can address fields of action that cannot be or are not addressed by Energy saving obligations for energy companies. For example; energy companies will run standard financial incentive programmes, while funds run motivation and information campaigns, promote innovative technologies and techniques, and address behaviours etc.

Other policies, such as Minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) and Mandatory comparative energy labels or Energy performance certificates, or RD&D funding can provide an important basis for the energy companies in terms of deciding which programmes/ measures to promote. Programmes implemented by energy companies under an ESO should target solutions exceeding MEPS in energy efficiency by far, such as super-efficient appliances. They can thus prepare the next revision of MEPS.

A number of structural pre-conditions are necessary to implement an ESO scheme.

Agencies or other actors responsible for design and implementation

An ESO scheme needs clear regulatory oversight in order to by really effective because there is the strong incentive for the energy companies to minimise both costs and actual energy savings that are additional to baseline energy efficiency trends, (as opposed to the energy savings calculated for proof of target achievement).

A government energy agency and or the energy regulator need to be in charge of developing the calculation methods for proof of target achievement. These agencies can involve stakeholders, and the law may allow obligated parties or even third parties in a ‘white certificate’ scheme to propose methods, as is the case in Italy, but government should retain the right of decision, so that the baselines reflect what markets would do without energy efficiency programmes and do not overestimate calculated savings in relation to actual savings.

The agency also needs to control the eligible actions. By way of example, as soon as the European Union decided to ban incandescent lamps from the market, the UK energy regulator disallowed the promotion of Compact fluorescent lamps for the British ESO scheme.

Finally, the agency needs to control monitoring, reporting and verification, and needs the ability to set penalties in case of non-compliance.

Test procedures

The ESO scheme needs test procedures for energy efficiency in two ways: for the definition of calculation methods for the proof of energy savings achieved, and for setting and communicating energy efficiency requirements for the actions promoted in the programmes that the energy companies implement to achieve their targets.

The ESO will, therefore, first rely on test procedures that were generated, e.g., in the preparation of MEPS and energy labels for both purposes. However, to the extent that such procedures do not (yet) exist for some types of action, specific test procedures for energy efficiency will need to be developed for the ESO scheme.

Others

An easy-to-monitor, consistent, and unequivocal set of calculation methods for the proof of energy savings achieved needs to be developed. It must cover all energy efficiency actions eligible for the scheme.

The agency and the energy companies need highly qualified staff with knowledge of energy efficiency solutions and potentials as well as programme design, implementation, and evaluation.

Important steps of policy design and implementation include (based on RAP 2012):

Setting policy objectives

The policy objectives of the ESO scheme should be simple and clear, and focussed on achieving energy savings. If the scheme has multiple objectives, the achievement of any non-energy-related objectives should not hinder pursuit of the primary objective to achieve energy savings.

Creating legal authority

A carefully selected combination of legislation, regulation, and ministerial and administrative processes to establish and operate the ESO scheme is advisable.

Defining coverage: fuels, sectors and facilities

This should reflect the overall policy objectives for the scheme and estimates of energy efficiency potentials for the different fuels, sectors and facilities. It will also reflect sector and fuel coverage by existing energy efficiency policies. Countries can also start by covering one or two fuels and then expand the scheme to other fuels as experience is gained.

Setting the energy savings target

Energy savings targets are an integral element of an ESO scheme. Setting the level of the energy savings target for the ESO scheme should reflect the overall policy objectives for the scheme and aim to strike a balance between making progress, the cost to consumers of meeting the target, and what is practically possible based on an assessment of energy efficiency potential. It is advisable to set the target in terms of final energy (i.e., the quantities of energy delivered to, and used by, consumers) unless the scheme covers several different fuels, in which case primary energy is more appropriate. Only if the scheme has a policy objective that relates to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction, policy makers can consider using carbon dioxide equivalent units. Setting targets for three-year periods has proven practical in many countries but a long timeframe for overall targets, preferably between 10 and 20 years, will increase security for all market actors. Calculating eligible energy savings over the estimated lifetime for each type of energy efficiency action will set the right incentives for the energy companies, but annual (first-year) energy savings should also be reported. In order to ensure that the energy companies do not focus on one or few types of energy efficiency actions but cover a broad range of potentials, the target should be set high enough and sub-targets may be set for different sectors or types of action.

Selecting the obligated parties

The obligated parties in the ESO scheme should be determined according to the fuel coverage of the scheme and the type of energy provider that has the infrastructure and capability to manage the delivery and/or procurement of eligible energy savings. It may be necessary to restrict the obligation to larger energy providers. Allocation of individual energy saving targets to each obligated party will be based on that party’s market share of energy sales or distribution.

Setting up the compliance regime

An integral component of the ESO scheme is a procedure for obligated parties to report claimed eligible energy savings to an appropriate authority and a process for checking and verifying these savings. A penalty needs to be imposed on obligated parties that fail to meet their individual energy saving targets. The level of the penalty must be high enough to mobilise energy providers to meet their targets. It could be a share of overall company turnover or a price to pay for every kWh not saved that is significantly higher than usual programme costs.

Considering performance incentives

It may be advisable to include performance incentives in the ESO scheme to be awarded to obligated parties that exceed their energy savings targets.

Defining eligible energy savings providers

Enabling non-obligated parties in the EEO scheme to implement energy efficiency projects to produce eligible energy savings will create competition with its economic benefits. The scheme should avoid unnecessary restrictions on the energy efficiency projects or measures that can be implemented to produce eligible energy savings, provided that the energy savings can be verified.

Defining eligible energy efficiency actions

Establishing in the ESO scheme a list of preapproved energy efficiency actions with deemed energy saving values will facilitate implementation of the scheme. However, the scheme should not limit the actions and measures that can be implemented to produce eligible energy savings to only those on the list.

Measurement, reporting, and verification

As an integral component of the ESO scheme, a robust system for measuring, reporting, and verifying energy savings and other activities that contribute to scheme targets needs to be established. We recommend that procedures to verify whether energy savings are additional to what would have happened in the absence of the ESO scheme are also established. This is the task of government, but the obligated companies should deliver the data required.

Ensure funding

As stated above, policy makers need to establish an appropriate mechanism in the ESO scheme to enable recovery of the costs incurred by obligated parties in meeting their individual energy saving targets.

Co-operation of countries

When setting up new ESO schemes, countries can learn from the experiences of others. Under existing schemes, both the regulatory agencies for the schemes and the obligated energy companies can gain a lot from exchanging experiences on energy efficiency programme designs, processes and subjects: What has worked and what has not? This also concerns the methods for calculating energy savings and the compliance regimes.

Monitoring

For the energy efficiency programmes offered by the energy companies, the regulator should request documentation from the energy companies in order to evaluate cost-effectiveness and allow cost recovery. Random checks of the accuracy of the documentation may be useful.

For evaluation of energy savings, the documentation should cover the number of participants or beneficiaries, the energy efficiency actions they have taken (e.g., purchase of energy-efficient buildings or refrigerators), and the unitary gross energy savings achieved by each action (either via agreed deemed savings or ex ante agreed calculations, or via ex-post evaluations) (cf also Staniaszek & Lees 2012). To ensure sufficient and useful monitoring and evaluation, data can be provided from the programmes. The provision of this data should be part of the funding requirements to programme beneficiaries.

For evaluating economic benefits and costs, energy companies need to provide evidence of their costs incurred separately, for the programme design, administration, communication and evaluation costs and for any financial incentives. They must also provide the incremental part of the energy or power (kW) prices that the participants/beneficiaries would have paid for the energy or power they saved. Furthermore, incremental costs incurred by the customers to invest in energy efficiency or operate their premises and equipment in an energy-efficient way need to be estimated via market monitoring or ex-post evaluation.

Evaluation

In order to be credible, evaluation should be done by independent institutes or consultants and not by the energy companies themselves, but costs can be included in the energy prices.

The possibilities and formulas for evaluating energy savings will depend on the type of energy efficiency action supported as well as the type of energy efficiency programme (e.g. information only programmes are more difficult to evaluate than financial incentive programmes -see our detailed files on these types of policies and measures). The same holds for economic benefits and costs from either the customer/participant perspective, or that of the national economy/society. The USA in particular has a long-standing experience in evaluation methods.

In addition to the data directly monitored for the energy efficiency programmes, evaluation of net energy savings compared to baseline trends should address side-effects such as rebound, multiplier, and free-rider effects, and the ‘lifetime’ and potential deterioration of energy savings.

For the economic benefits from the perspective of the national economy/society, standard values for the incremental energy supply costs that will be avoided in the long run for a kWh of energy or a kW of load should be developed by the regulatory authority.

Sustainability aspects

It depends on target setting, whether there is an incentive or even a requirement for the obligated energy companies to also promote sustainability aspects other than energy savings. For example, the UK government has required that 40 % of the energy savings in the ESO scheme are achieved for low-income customer groups, so as to reduce fuel poverty (the UK scheme only targets the residential sector). The specific calculation methods for energy savings could provide bonuses e.g. for water savings for clothes or dish washers, or limits on water consumption.

Co-benefits

It will depend on the scope and design of energy efficiency programmes implemented under an ESO scheme and on the incentives as mentioned here above, what kind of co-benefits (i.e. “non-energy benefits” such as health improvement, labour market effects etc.) may arise from implementing the ESO scheme. The increasing demand of energy efficiency products and services induced by the implementation of the ESO scheme may enhance the job market in these fields.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy:

It may be difficult and take quite some time to define the methods for calculation of energy savings required to prove target achievement.

There may also be a lack of experience in energy companies with energy efficiency programmes and projects.

In addition, there may be a lack of energy consultants in the market.

Furthermore, experience shows a tendency of “cherry-picking” among the energy companies - they focus on one or a few types of energy efficiency actions that are the easiest and cheapest to implement, which means lost energy efficiency opportunities in other market segments.

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers:

Regarding methods for calculation of energy savings, countries starting to introduce an ESO scheme can learn from others with more experience. It is advisable to start with pragmatic approaches, but to update methods and baselines at least every three years to reflect and stimulate market dynamics for energy efficiency.

If there is a lack of experience in energy companies with energy efficiency programmes and or a lack of trained energy consultants, policy makers may start with moderate targets having already decided to communicate their intention to ramp them up each year and each target period. This has been the case in many countries.

In order to ensure that the energy companies do not focus on one or few types of energy efficiency actions but cover a broad range of potentials, the target should be set high enough and sub-targets may be set for different sectors or types of action.

The most successful countries or states achieve gross energy savings equivalent to around 2 % per year and more of the target groups’ energy consumption through energy saving obligations. These include Denmark (around 2 %), Massachusetts (2.4 %), and Vermont (just under 2 %) (RAP 2012). Up to 1.5% per year of these savings are additional to baseline trends of energy efficiency (Thomas 2007; RAP 2012).

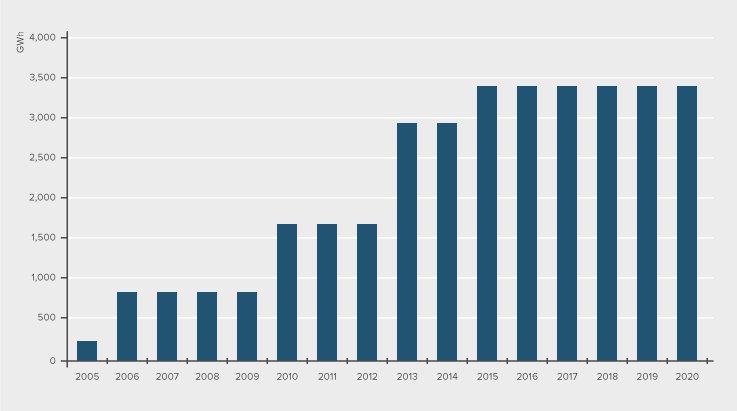

The graph shows how Denmark continues to increase its energy savings targets for the energy companies to achieve.

In well-designed ESO schemes, the cost of saving a kWh of energy is usually lower, often much lower, than the cost of the energy supply saved.

The obligated parties will usually carry a certain share of the incremental cost of energy efficiency improvements via financial incentives or sometimes by providing technology (such as Compact fluorescent lamps) for free. In addition, there are costs of programme management and communication, for paying out financial incentives to consumers, and for monitoring, reporting and verification. In well-designed programmes, the latter are around 20 % of the financial incentives provided, e.g., 18 % in the UK (Lees 2012).

The total average programme costs for energy companies may vary between 0.5 and 4 Eurocents per kWh of energy saved, with an average between 2 and 3 Eurocents, depending on the level of targets and the type of programmes (RAP 2012; Lees 2012).

There is evidence that with increasing experience, companies can deliver targets at lower costs to themselves and to consumers. For example, in the UK, despite ever-increasing energy savings targets, the cost to all parties (energy companies, consumers who benefit and others) for saving a kWh of electricity halved to 0.9 pence (1.1 Eurocent) between 1994 and 2008, and for gas it halved to 0.5 pence (0.6 Eurocent) between 2000 and 2008 (Lees 2012). On the other hand, with targets increasing towards 2 % per year, total costs to society may increase as well. In Denmark, they increased from 4.5 Eurocents per kWh in 2005 to 2009 to 5.6 Eurocents per kWh in 2011.

Usually, the programme costs of the energy companies will finally be carried by energy consumers via their energy prices or tariffs. The price elements have usually been between 0.1 and 0.3 Eurocents per kWh, but may increase to 0.5 Eurocents where savings targets are increasing towards 2 % per year (RAP 2012). However, the energy bills of consumers as a whole (which are obtained by multiplication of a much lower energy consumption and a slightly increased price) will decrease as the energy savings are cost-effective (see below). Furthermore, energy savings will defer investment in new power plants and grid expansions and or reduce the market price for energy, which should also reduce energy prices.

There is also a cost for regulatory oversight of the scheme, particularly of auditing and verifying the energy saving projects and ensuring that the energy company has met their target; this cost is borne out by the administrator of the scheme. This is a very small cost, e.g. the British energy regulator, Ofgem, estimated that its costs are less than 0.1% of the energy supplier costs in 2010 (Lees 2012).

In most ESO schemes, the expected cost savings have been much higher than the cost of saving energy, and there is a substantial net benefit both for consumers and society.

For the European Union, Bertoldi et al. (2010) tried an independent comparison of economic impacts of the ESO schemes for France, Italy and GB. In all cases, the total cost estimates of saving a unit of electricity or gas are lower than the electricity and gas residential prices by a factor varying between 2 and 6.

Similar results have been achieved in the USA. For example, in Massachusetts, programme costs for electricity savings were around US$ 235 million, while lifetime economic benefits (cost savings) were just over US$ 1,100 million – 4.5 times as high as costs. Results for programmes saving natural gas were similar (RAP 2012). Generally, the energy savings are cost-effective in all states with ESO schemes, also because regulators make sure they are.

York, Dan; Molina, Maggie; Neubauer, Max; Nowak, Seth; Nadel, Steven; Chittum, Anna; Elliott, Neal; Farley, Kate; Foster, Ben; Sachs, Harvey; Witte, Patti (2013): Frontiers of Energy Efficiency: Next Generation Programs Reach for High Energy Savings. January 2013. ACEEE Report Number U131. www.bigee.net/s/1s8cjv

|

|

Utilities’ Refrigerator replacement programme

Type: Financial incentives |

Brazil |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy