Bulk purchasing and co-operative procurement works through gathering large buyers (private and public). It is useful for promoting very energy-efficient products already available on the market (BAT) or new, even more energy-efficient appliances (‘technology procurement’). The resulting demand volumes can induce manufacturers to develop, produce and market these technologies and equipment, increase market penetration, and reduce market prices for these technologies. This in turn will lead to these technologies being used even more often and eventually becoming the default technology in new construction.

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

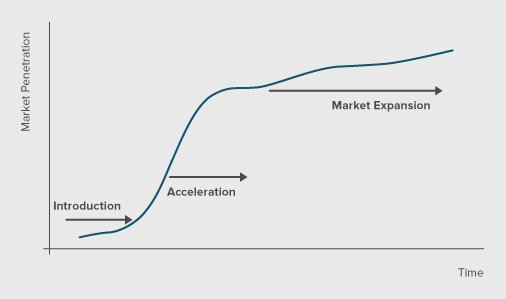

Co-operative procurement aims at the introduction of innovative energy-efficient products into commercial use, opening up new choices for investors and users (ten Cate et al. 1998). The objective can either be to increase the production and market volumes of highly energy-efficient appliances (best available technologies—BAT) or to bring new, even more energy-efficient appliances (best not yet available technologies—BNAT) to the market. Co-operative procurement aims to use the market influence of a group of large buyers to stimulate the production of, and to establish a significant demand for energy-efficient products. This type of policy holds significant promise to introduce, accelerate, and expand the market for very energy-efficient appliances.

Worldwide implementation status

One of the first technology projects was a refrigerator/freezer programme from Sweden, which started in 1989. A group was created, consisting of leading buyers. They represented about 40 per cent of the market for combined refrigerators/freezers. Purchase of a symbolic first series of 500-1,000 units of a frequently used model was guaranteed. The goal was formulated in the functional term of kWh per equivalent volume in litres and year. The newly developed refrigerator/freezers used a third less energy than the best ones available on the market before (Westling 1999). Sweden has implemented more than 50 different technology procurement projects between 1990 and 2005 (in the buildings, industry and traffic sector) (Stigh 2007).

Several other programmes followed the Swedish example. Another example is the successful Energy+ project (2006-2009). It contributed to creating a first market for the new generation of highly energy-efficient heating and hot water system circulators. Circulators in the EU have a very large energy saving potential of more than 30 TWh/year of the total electricity consumption. The IEA ran a number of multinational pilot schemes for technology procurement too, including one on electric motors.

Governance level

The policy can be implemented on a regional, national and trans-national level. Most of the time the policy was implemented on national level. At this level, a large enough buyer group may be more easily gathered than at a regional level only, while there are no problems with different languages or procurement rules between countries that may arise in a transnational approach.

In principle the type of appliance is unlimited.

Co-operative procurement programmes perfectly and reciprocally reinforce with other policy instruments. An example for additional measures is the provision of information through buyer education elements for instance, retailer promotion, and information campaigns. These procurement and information activities work best if based on an energy label. Buyers and users can be informed about the energy and cost-effective alternatives and saving options during the use phase (Mäkinen & Neij 2010).

Labels and standards can also help to set energy performance requirements for the co-operative procurement and to identify the inefficient conventional technologies. Co-operative procurement programmes can in turn help laying the groundwork for future minimum energy performance standards.

An award for the winning appliance in a technology procurement, aiming at new products with higher energy efficiency than currently on the market, can also be a measure to underline the visibility of the manufacturer of the best product and to promote the programme. A market procurement too can be combined with an award competition, as the Energy+ project did for example. The difference to the bigEE policy type ‘Competitions & awards’ is that co-operative procurement gathers a group of active buyers complementarily to the competition.

In addition the effect of co-operative procurement programmes can be enhanced through co-ordinated rebate programmes. In the Swedish technology procurement programme, such rebates have been awarded e.g. to the buyers of a symbolic first series of 500-1,000 units in the project on very energy-efficient combined refrigerators/freezers, in that case, equivalent to ca. €100 (Westling 1999, converted to EUR(€) by bigEE team). The Netherlands provided special rebates for the refrigerators and freezers qualifying for the European Energy+ co-operative procurement project in 2002 and 2003 (read more in the bigEE good practice policy examples on Energy+ and the Dutch EnergiePremieRegeling).

The following pre-conditions are necessary to implement Co-operative procurement

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

Public agencies, authorities or energy companies can play the crucial role of the facilitator for the co-operative procurement or a supportive role such as providing information to the public. They should have appropriate expertise in energy efficiency. The authority must be able to establish and sustain an open communication among the different actors (buyers and manufacturers). It is important to understand and weigh the interests of all different actors and to find good reasons for all parties to participate (ten Cate et al. 1998).

Funding

Funding is necessary for providing large buyers and manufacturers with information or technical assistance and to co-ordinate the programme (co-ordination of the different actors). If the programme is combined with a rebate programme, funding will be required for this financial incentive too.

Test procedures

A set of calculation methods to rate the innovative products and to identify the winner is required. It will be best if methods from an energy label can be used. Otherwise, the set of methods will need to be developed.

Proper planning of the procurement process before the procurement is essential. This should include the consultation with stakeholders (large buyers) about what they want and need and the available budget. The creation of buyer groups and networks is the most important step (Westling 1999). Large buyers should be identified with common interests in purchasing very energy efficient products. To convince manufacturers that there is a demand, the project manager should work together will all relevant target groups. At the same time the market situation should be analysed including the best available technology on the market and the baseline.

Then the development of technical requirements (including additional performance features like noise, emissions but also timing, test methods etc.) and the bidding (in the case of technology procurement) or the listing of qualifying products (in the case of market procurement) follows. Energy efficiency must become a central criterion in the procurement process. After the definition of specifications it is important to guarantee a fair, open and transparent procurement process (OGC 2008). The product development needed in the case of technology procurement can vary in length, depending on the required technology developments.

For technology procurement, after a defined period of time the selection of one or more winners from the bid follows. The jury may announce one or multiple winners depending on the design of the policy (the winner can be the first manufacturer that developed the product with the defined criteria or multiple manufacturers who met the minimum requirements). The winner should receive a guaranteed initial order sufficient to begin the production of this new product (ten Cate et al. 1998). In market procurement, these steps are not necessary but there will be lists of qualifying products meeting the energy efficiency and other specifications as well as lists of interested buyers and possible lists of supporters. However, if there is an award competition as an element of the co-operative procurement scheme, there also has to be a selection of one or more winners.

An important step is the marketing and consumer education to maximise the purchase of the newly available appliances. The marketing step is the true test of a procurement programme’s success (ten Cate et al. 1998).

The policy should include a monitoring and evaluation process.

Quantified target

Co-operative procurement policies are more effective with quantified targets. Concrete targets, such as the number of appliances that the buyers commit to purchase, should be defined in order to calculate the energy saving potential and the achieved energy savings. “Goals and targets should also assign responsibility and timetables for data collection and progress reporting” (Harris et al. 2005).

International co-operations

Several countries worldwide have already introduced co-operative procurement programmes. Therefore co-operations are helpful for countries, which plan to implement similar measures. The co-operation can help policy makers to improve the design and implementation of specific policies.

Furthermore, in many cases manufacturers and large buyers are very fragmented in one country but markets may be international. Joint actions involving several countries can give stronger signals to develop energy-efficient products. Examples are the European Energy+ project (cf. the bigEE good practice policy example) and the IEA’s international co-operative procurement projects.

Monitoring

In order to be effective, the implementation of co-operative procurement programmes should be monitored and tracked. The number of winning or qualifying products purchased by the buyers group and the energy efficiency improvements achieved should be reported to responsible authorities.

Evaluation

Responsible authorities like energy agencies or research institutions should carry out an evaluation of the energy and cost savings and the cost-effectiveness of co-operative procurement programmes. Key information includes: an overview of the products purchased, the changes in the product range of suppliers and the resulting development of the market. Other factors are the number, variety and (additional) costs of energy-efficient appliances and the costs for all market actors.

Design for sustainability aspects

Other sustainability aspects and environmental impacts can (and should) be part of an energy efficient procurement programme, e.g. health aspects or other resources such as water and detergents. Other criteria are the consideration of SMEs, working conditions etc.

Co-benefits

Procurement programmes may create appliances with better services and may improve the competitiveness of manufacturers and purchasers’ employee productivity.

“Reduction of energy use by half, reduction of total costs almost by half, and/or speeding-up the development process and the realisation of individual projects are results achieved by using co-operative or technology procurement (Westling 1999)”. The table below presents some examples.

For the co-operative procurement scheme Energy+ (cf. the bigEE good practice policy example), which ran from 1999 to 2004, the project team estimated energy savings of between 9.3 to 15.5 GWh in EU-15 annually for the initial project phase (1999-2001). Including the second project phase (2002-2004), estimated cumulative energy savings that can be attributed to Energy+ amount to about 100 GWh (0.36 PJ) (Labanca 2006). Apart from showing that co-operative procurement on a transnational level is possible, Energy+ is considered to be part of the reason why “A+ and A++ appliances are f25% (up to 64%) more efficient than basic Class A models” (Nordic Council of Ministers 2008, p. 56).

| Project area | Result | Energy reduction |

| Refrigerator/Freezers | Brought energy consumption from 1.2 to 0.8 kWh per litre of comparable volume per year | By 33% |

| Clothes washers & dryers for laundry rooms | From 2.6 to 1.2 kWh/kg of laundry | By 50% |

| Ventilation, Replacement of fans in residential area | From 750 to 380 kWh/apartment and year | By 50% |

| Windows | From 5,900 to 3,300 MWh/year in one project | By 44% |

| Heat pumps | Two suppliers chosen for development and deliveries | By 30% |

Source: Westling 1999

Comparing the estimated cost of the Energy+ programme of 1.2 €cent/kWh (see Actual costs above) with EU electricity wholesale market prices of 4 to 6 €cent/kWh, the programme was clearly cost-effective. This is also very likely for most consumers who purchased Energy+ appliances. Their saved energy costs are much higher—between 10 and 25 €cent/kWh, yielding annual savings of €20 to €50 if an Energy+ refrigerator or freezer saved on average 200 kWh/year, as has been estimated (Labanca 2006). This is likely to be much higher during the estimated 15 years of lifetime compared to an estimated incremental purchase cost of 10 to 25 %, which might be a range between €50 and €250. In addition, the Dutch rebate scheme drove down the incremental cost of energy-efficient refrigerators and freezers (read more in the bigEE model example of good practice on the Dutch EnergiePremieRegeling).

|

|

Energy+: Aggregated purchase at European level for A-rated fridge/freezers

Type: Co-operative procurement |

Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, United Kingdom, Belgium, Greece, Norway, Switzerland |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy