Energy efficiency funds are special entities founded and funded by the state for organisation and funding of energy efficiency programmes. These programmes typically combine information, motivation, financial incentives and or financing, capacity building, and RD&D/BAT promotion. Energy efficiency funds (also known as energy efficiency trusts) can implement such programmes as an alternative to, but also jointly with energy companies or the government itself.

Energy efficiency funds or trusts may be given greater flexibility in implementing energy efficiency programmes than government agencies or energy companies, and may receive a stable funding by creating dedicated levies or taxes on energy to feed the fund or trust.

Several successful examples around the world show that Energy efficiency funds can achieve gross energy savings equivalent to 2 % per year and more of the target groups’ energy consumption, of which up to 1.5% per year are additional to baseline trends of energy efficiency. Usually, these energy savings are cost-effective for consumers and society.

Energy efficiency funds are entities that manage and distribute financial support to energy efficiency programmes. They can also co-ordinate or implement such programmes themselves. Since the financial assets for Energy efficiency funds usually derive from public sources, they are mostly set up by public entities. However, their implementation may also be affiliated to private institutions. Among the different types of funds, this text focuses on grant-giving funds rather than e.g. revolving funds (information on the latter can be found in the bigEE file on Financing).

The supported programmes typically combine information, motivation, financial incentives and or financing, capacity building, and RD&D/BAT promotion, etc. Such programmes are especially useful for end uses or sectors that require complex optimisation and thus cannot fully be addressed by Minimum energy performance standards (MEPS), or for promoting solutions and technologies significantly more energy-efficient than required by MEPS. Energy efficiency funds and their programmes can thus complement such regulatory policies as MEPS.

The energy savings and the cost-effectiveness of Energy efficiency funds highly depend on the programmes that are supported by the fund. Several successful examples around the world show that Energy efficiency funds can achieve gross energy savings equivalent to 2 % per year and more of the target groups’ energy consumption, of which up to 1.5% per year are additional to baseline trends of energy efficiency. Usually, these energy savings are cost-effective for consumers and society.

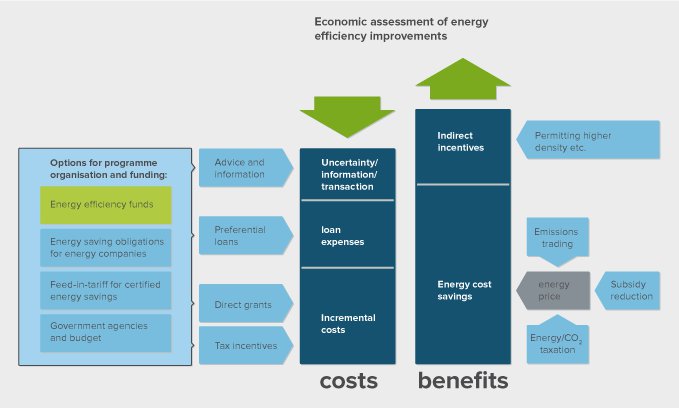

The graph shows how Energy efficiency funds enable the implementation of different types of energy efficiency programmes that reduce costs and barriers for energy efficiency improvements.

As the graph shows, Energy efficiency funds can be an alternative to, but also co-operate with energy companies (cf. bigEE information on Energy saving obligations for energy companies) or the government itself (cf. bigEE information on Government agencies and budget) as a means to implement energy efficiency programmes.

The funding for an Energy efficiency fund can be provided from the government’s budget. However, funding through a special levy, tax, or revenue from sale of emissions allowances is quite common and allows a more stable level of income than yearly budget allocations, which are often subject to political fluctuations. Climate finance (particularly Programmes of Activities – PoA – under the Clean Development Mechanism – CDM and Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions – NAMAs) can be used by developing countries and emerging economies to (part-)finance energy efficiency funds.

AdvantagesCompared to implementation through government agencies and budget or energy companies, Energy efficiency funds may allow the following advantages:

|

Disadvantages

|

Energy Efficiency Funds aim at increasing energy efficiency by implementing or supporting related programmes. They initiate programmes, implement programmes or allocate financial assets for external programmes.

Mostly national, maybe supra-national or trans-national (revolving funds created in Eastern Europe from development aid), may also be regional or local (e.g. ProKlima Fonds - Hannover).

In principle, an Energy Efficiency Fund can support the market introduction or breakthrough of the most energy-efficient appliances.

For example:Through the support of different programmes, the Energy Efficiency Fund can and should address a very wide range of target groups:

As the programmes usually combine information and financial incentives or financing, in most cases the direct beneficiaries will be investors and users of energy-efficient appliances.

The indirect beneficiaries of an Energy efficiency fund are numerous and vary depending on the supported programmes.

Energy efficiency funds can be used alternatively or complementary to Energy saving obligations for energy companies or to relying on Government agencies and budget for programme implementation. When used complementarily, the fund can address fields of action that cannot be or are in reality not addressed by Energy saving obligations for energy companies. For example: Energy companies will run standard financial incentive programmes, while funds run motivation and information campaigns, promote innovative technologies and techniques, address behaviour, etc.

Other policies, such as Minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) and Mandatory comparative energy labels or Energy performance certificates, or RD&D funding can provide an important basis for the Fund in terms of deciding which programmes/measures to promote. Programmes implemented by Energy efficiency funds should target solutions exceeding MEPS in energy efficiency by far, such as super-efficient appliances. They can thus prepare the next revision of MEPS.

Agencies or other actors responsiblefor implementation

Energy efficiency funds are designed by governments and implemented as a newly founded entity, which can be affiliated to a private or public institution (e.g. Ministry) or form a new institution itself.

Funding

The fund needs to have sufficient resources that it can allocate to various programmes.

Test procedures

No specific test procedures for energy efficiency are needed for the fund itself, but the programmes it implements will rely on test procedures generated, e.g. in the preparation of MEPS and energy labels.

Others

The fund needs highly qualified staff with knowledge of energy efficiency solutions and potentials as well as programme design, implementation, and evaluation.

Quantified target

Energy efficiency funds can aim to achieve quantified energy savings targets (e.g. Danish Electricity Savings Trust, ENOVA, Efficiency Vermont)

Co-operation of countries

When setting up new Energy efficiency funds, countries can learn from the experiences of others. Existing funds can gain a lot from exchanging experiences on energy efficiency programme designs, processes and subjects: What has worked and what has not?

Monitoring

The impact of Energy efficiency funds needs to be measured indirectly by monitoring and evaluation of the supported programmes.

For evaluation of energy savings from the programmes, the documentation should cover the number of participants or beneficiaries, the energy efficiency actions they have taken (e.g. purchase of energy-efficient refrigerators), and the unitary gross energy savings achieved by each action (either via agreed deemed savings or ex-ante agreed calculations, or via ex-post evaluations). To ensure sufficient and useful monitoring and evaluation data can be provided from the programmes, the provision of this data should be part of the funding requirements to programme beneficiaries.

For evaluating economic benefits and costs, Energy efficiency funds need to monitor their costs incurred, separately for the programme design, administration,communication and evaluation costs and for any financial incentives. They should also monitor the incremental part of the energy or power (kW) prices that the participants/beneficiaries would have paid for the energy or power they saved. Furthermore, incremental costs by the customers to invest in energy efficiency or operate their premises and equipment in an energy-efficient way need to be estimated via market monitoring or ex-post evaluation.

Evaluation

In order to be credible, evaluation should be done by independent institutes or consultants and not by the Energy efficiency funds themselves.

The possibilities and formulas for evaluating energy savings will depend on the type of energy efficiency action supported as well as the type of energy efficiency programme (e.g. information only programmes are more difficult to evaluate than financial incentive programmes, see our detailed files on these types of policies and measures). The same holds for economic benefits and costs from either the customer/participant perspective or that of the national economy/society.

In addition to the data directly monitored for the energy efficiency programmes, evaluation of net energy savings compared to baseline trends should address side-effects such as rebound, multiplier, and free-rider effects, and the ‘lifetime’ and potential deterioration of energy savings.

For the economic benefits from the perspective of the national economy/society, standard values for the incremental energy supply costs that will be avoided in the long run for a kWh of energy or a kW of load should be developed by the government.

Sustainability aspects

Energy efficiency funds should design their programmes to promote sustainability aspects (like resource efficiency or health aspects.

Co-benefits

All kinds of co-benefits (i.e. “non-energy benefits” such as health improvement, labour market effects etc.) may arise from implementing these programmes, depending on their scope and design.

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy:

The main challenges for successful Energy efficiency funds concern organisational and financial barriers. Existing institutional capacities may often not be sufficient to manage an Energy efficiency fund, so the fund needs to be well established and organised as a new entity in order to co-ordinate different programmes successfully. Moreover, it needs sufficient financial assets to support different programmes addressing various energy efficiency actions. Moreover, a lack of information and motivation to the beneficiaries may diminish the demand for the fund’s assets and thus hamper its success.

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers:

It is a matter of political will to provide sufficient resources for management and programme implementation to an Energy efficiency fund. A strong top management is also important. There must also be sufficient resources for communicating the fund’s programmes and their benefits to the target groups.

With a strong supporting framework for the organisation and funding of energy efficiency programmes, such as Energy efficiency funds, energy savings in addition to baseline efficiency trends that are equivalent to at least 1% to 1.5% of annual energy consumption can be achieved at net macroeconomic gain. This has been demonstrated by successful Energy efficiency funds like Efficiency Vermont from the USA or ENOVA from Norway, as well as others (Thomas 2007).

The costs of an Energy Efficiency Fund can be individually decided depending on the savings target and the range of addressed fields of action. However, it needs to be ensured and monitored that the financial resources are sufficient to reach the envisaged targets. Typical ranges are equivalent to between 0.1 and 0.4 Eurocents per kWh of energy consumed by the target groups, as seen for the examples of Efficiency Vermont from the USA or ENOVA from Norway.

Staff of Energy efficiency funds ranges from six in Denmark (Danish Electricity Savings Trust) to 60 in Norway (ENOVA) and the cost of managing the fund is usually only a few per cent of its total budget.

If well designed and implemented, the energy efficiency programmes will be cost-effective for consumers and society. This is very likely and is the case, among others, for the example of Efficiency Vermont, which has achieved net benefits for consumers worth 2.2 to 2.4 times its costs.

York, Dan; Molina, Maggie; Neubauer, Max; Nowak, Seth; Nadel, Steven; Chittum, Anna; Elliott, Neal; Farley, Kate; Foster, Ben; Sachs, Harvey; Witte, Patti (2013): Frontiers of Energy Efficiency: Next Generation Programs Reach for High Energy Savings. January 2013. ACEEE Report Number U131. www.bigee.net/s/1s8cjv

Further information

Website Effciency Vermont: www.bigee.net/s/ty747n

Website ENOVA: www.bigee.net/s/tnib83

Website The Danish Energy Savings Trust: www.bigee.net/s/dxpigh

|

|

Energy Efficiency Utility Program of Vermont

Type: Energy efficiency funds |

United States |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy