Mandatory comparative energy labelling is crucial to make the market offer of standard appliances or systems transparent regarding energy consumption and energy costs. Such labels are the basis for other information and for financial incentive policies and programmes. Comparison labels allow consumers to judge the energy efficiency and relative ranking of all products that carry a label. In order to provide complete market transparency, it must be mandatory by law for manufacturers and retailers.

Comparison labels allow consumers to judge the energy efficiency (or energy consumption) and relative ranking of all products that carry a label in defined product and energy efficiency categories. This type of label allows consumers to easily assess the efficiency of a product in relation to an absolute scale, by means of a simple numeric or ranking system. The concept is that it is much easier for a consumer to remember and compare a simple ranking scale (such as 1, 2, 3 or 1 star, 2 star, 3 star or A, B, C) than to remember and compare energy consumption values (CLASP, 2004). In order to provide complete market transparency, it must be mandatory by law for manufacturers and retailers to apply the label to each single product of a type of appliance subject to labelling. Energy labels are designated to provide information on energy efficiency, energy consumption or performance of the product. The best option here is to provide the annual energy consumption in accordance with the test standard, so that consumers can calculate the running costs for energy.

Various types of energy label programmes have been developed reflecting each country’s status of economy, technology, industry and appliance market. The website www.clasponline.org provides a comprehensive overview of comparison energy labels worldwide.

An advantage of a ‘categorical’ labelling scheme in comparison to energy efficiency endorsement labels is that it is often easier, with the former, for consumers to understand and to transfer their understanding of the categories from one product purchase to others.

The labelling scheme must allow end-users to easily compare which product is more resource efficient during its use phase than another, thus avoiding buying products that are cheaper at the time of purchase but more expensive over their life cycle. Once a label shows that it has an impact on consumer choice, manufacturers are likely to be motivated to enhance energy efficiency of their products. Furthermore, mandatory energy labels induce retailers to stock and promote energy-efficient appliances. Altogether, mandatory comparative energy labels provide the means to inform consumers of the product’s relative or absolute performance and (sometimes) energy operating costs (IPCC 2007). They are, thus, the basis for other information instruments, such as databases of energy-efficient appliance models, targeted advice to consumers, information campaigns, and for financial incentive schemes.

Mandatory labelling schemes have already been successfully implemented all over the world with high energy savings. They play an increasingly important role in national energy efficiency promotion strategies. For example, European estimations show that the average energy efficiency of domestic cold appliances increased by 37% and at an average rate of 4% annually since the introduction of the mandatory EU energy label (Waide & Egan 2005).

Furthermore, mandatory energy labelling schemes are regarded as a main driver for innovation within the industry. It is a main product differentiator leading to improved competiveness (European Commission 2009).

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

Mandatory labelling schemes aim to make energy consumption of products on the market transparent to buyers. They thereby have the effect to increase the average energy efficiency of products and ultimately allow to remove the least energy-efficient models from the market.

The implementation strategy pursued with mandatory energy labels is two-fold. They inform potential purchasers of the energy consumption (and other emissions e.g. noise) of the market offer, so consumers can take account of this and of the resulting running costs before making purchase decisions. The Directive also incites manufacturers to produce more energy-efficient appliances and retailers to stock and promote them, by enhancing their confidence that such energy-efficient appliances will find a significant market.

Worldwide implementation status

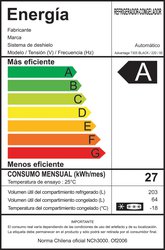

Most developed countries have some sort of mandatory energy labelling. Also some developing and emerging countries introduced mandatory labelling schemes. Categorical labels are for example in use in Europe, Australia, Brazil, China, India, Thailand, and other Asian countries. A selection of different country-specific labelling schemes can be found in the next figures. See also www.clasponline.org.

Governance level

In most cases, mandatory energy labelling schemes were introduced at national level. In some cases, the same label was implemented in a group of several countries at the same time (e.g. the European Union includes 27 countries).

The labelling schemes cover primary household appliances but in principle the technological focus is unlimited and all technologies can be covered by the labelling scheme for which a standard test procedure can be defined. In most countries, a mandatory labelling scheme was primarily introduced for refrigerators, room air conditioners, washing machines and similar appliances.

Mandatory labelling schemes can perfectly interact with minimum energy performance standards, information programmes, financial incentives, and energy-efficient procurement programmes.

In contrast, voluntary endorsement labelling schemes for the most energy-efficient appliances should not be introduced in parallel with mandatory comparative energy labels, as the latter already include energy classes with high energy efficiency and the former would thus only confuse consumers. On the other hand, a voluntary eco-label can inform about other environmental features of appliances. It can therefore go together with a mandatory comparative energy label, but should adopt the requirements of the most energy-efficient class(es) of the latter as its energy requirement.

Minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) usually focus on removing the least energy-efficient products from the market. In contrast, labelling schemes drive the market towards best available technology and in so doing, prepare next steps in making MEPS dynamic. Minimum energy performance standards pay no attention to consumers and their potentials to influence the market. Energy labels and the instruments based on them, such as, product databases, financial incentives, and public and co-operative procurement, can close this gap.

Furthermore, mandatory energy labelling schemes can help to develop MEPS and should use calculation methods harmonised with those for MEPS. Also for incentives, a comparative energy label is a useful tool to detect the products, which can then be chosen for a financial support.

Structural pre-conditions are an agency, a funding scheme and an independent test procedure.

Agencies or other actors responsible for implementation

An agency or similar organisation is necessary to guarantee market surveillance and monitoring and to ensure compliance with the manufacturer obligations to correctly declare the energy consumption and the retailer obligations to correctly display the energy label.

Funding

There is no large funding scheme necessary, except for the development and update of the scheme and for the compliance monitoring.

Test procedures

A test procedure is necessary to calculate the standard energy consumption and to define energy efficiency classes.

Before the introduction of the label, a technical and economic study is necessary, which looks into the range of energy and service performances available amongst products on the market offering similar functionalities, the potential for improvement and the related costs (stock, sales, consumer behaviour etc.). This phase can be done perfectly in accordance with the preparation of minimum energy performance standards. The integration of all relevant stakeholders and ideally, dialogue with trading partners follows. The next steps are the selection of relevant product groups and the definition of a measuring method and test standards (unless it already exists). A monitoring and evaluation system is essential to control the effectiveness. Depending on national circumstances, the regulation must be adopted by public authorities to realise binding requirements for products, which are placed on the market. A regular update of the label in accordance with the development of the market is important to guarantee lasting results.

Quantified target

The policy can and should have a quantified target. The effectiveness can be evaluated through the market development of very efficient appliances (number of units sold in the most energy-efficient classes of the label).

Co-operations of countries

Several countries worldwide have already introduced mandatory labelling schemes. Therefore co-operations are helpful for countries, which plan the introduction of a mandatory labelling scheme. Advantages and disadvantages can be exchanged to make it easier to transfer the policy according to national circumstances.

Monitoring

Monitoring is very important to verify correct labelling. Monitoring and evaluation for mandatory labelling schemes can have two subjects: the compliance and the impacts and costs.

Compliance monitoring is essential for the instrument to function. If a large number of products, which are not compliant with the labelling rating are on offer, this will undermine the effectiveness of the instrument directly.

The impact can be monitored quite well when counting the sales figures per energy label category. It is essential to calculate energy but also cost savings and to evaluate barriers and incentives for future policies. However, there may – and should – be a package of instruments targeting energy efficiency of appliances (see above). Therefore, sales figures per energy label category will not only reflect the impact of the labelling scheme. Whether it will be useful and possible to attribute shares of the overall impact to individual instruments such as an energy label, will need to be assessed.

Evaluation

Energy agencies or research institutions can carry out an evaluation of the labelling scheme. Key information includes: the changes in the product range of suppliers and the resulting development of the market, the impact monitored for the whole package of policies and to the extend possible, the part attributable to the labelling scheme, the number, variety and (additional) costs of energy saving measures, the costs of the labelling scheme for all market actors and for the government.

Sustainability aspects

The label offers the opportunity to rate the energy consumption but also other performance characteristics like water consumption, noise, cooling characteristics, the availability of an on/off button or other characteristics which could increase the resource efficiency. That is why a preparatory study with a life cycle analysis is essential to cover all relevant aspects and to enlarge the focus (not only energy efficiency).

The following barriers are possible during the implementation of the policy:

Problems can arise with the lack of a sufficient market surveillance and enforcement by national authorities, both in respect to manufacturers meeting the set requirements and retailers displaying correct information.

Another barrier is the update of the requirements for the ranking of all available products within a product group. The label should be revised regularly in accordance with the market development.

Yet another barrier is/are possible delays in the development of the calculation method and the legislation process.

The following measures can be undertaken to overcome the barriers:

To overcome possible implementation barriers sufficient market surveillance should be guaranteed. A system of regular monitoring is essential to update the label at the right time.

High energy savings can be realised, especially when considering the labelling scheme as an element of a policy package which consists of MEPS, procurement programmes, financial incentives and information campaigns. While standards cut the less efficient products from the market, the voluntary label grants a best in class label for the upper end products. Mandatory comparative energy labelling complements this picture in providing compulsory comparative information on energy performance between these two extremes.

Labelling programmes play an increasingly important role in national energy efficiency promotion strategies but only a few reports deal with the various parameters which affect the impact and success of such national programmes.

For the European mandatory energy label some evaluations with saving potentials were calculated. Waide et al. (2005) claim that the EU energy label “has been an undeniable success in terms of market transformation impacts” for the case of domestic cold appliances on the EU level. Estimations show that the average energy efficiency of domestic cold appliances increased by 37% at an average rate of 4% annually since the introduction of the EU energy label. Furthermore, Waide et al. (2005) claim that the design of the EU energy label did not only stimulate a higher demand for energy efficient domestic cold appliances by consumers but also stimulated manufacturers to develop and supply appliances which reach a certain energy efficiency threshold in order to meet current and anticipated demand by consumers. Due to the categorical scale of the EU energy label with higher energy efficiency thresholds, manufacturers were challenged to develop higher efficient products.

In many cases, there is an increase in manufacturing cost to manufacturers for appliances with enhanced energy efficiency, which can be passed on to the users or can be compensated by productivity gains.

This means that at any given time, there is likely to be a price premium of energy-efficient models over less efficient ones for consumers. However, studies found purchase prices for energy-efficient appliances have decreased over time in the EU and Australia (Lane 2011).

Other studies show that labels for promoting energy-efficient appliances have not increased consumer prices significantly (IEA 2007).

The energy labelling scheme itself will also entail some costs to governments, manufacturers and retail. However, they are usually small in comparison to the incremental manufacturing costs.

According to Bertoldi & Atanasiu (2007), most of the energy efficiency measures like energy labelling schemes are cost effective. This means that they will result in net money savings for the users, as the reduced electricity costs over the lifetime of the appliance will be bigger than any additional purchasing cost for the more efficient model.

Manufacturers also seem to realise net benefits from higher market share of energy-efficient products as a consequence of energy labelling. For example, over the last ten years the EU white goods manufacturers have become more profitable, appliances cost less, and the efficiency has improved.

Overall, it can be concluded that energy efficiency measures and in particular labels are cost effective for society and reduce CO2 emissions at a negative cost.

|

|

EU Energy Label

Type: Mandatory comparative labelling scheme |

European Union (EU), |

makes energy efficiency in buildings and appliances transparent. For investors, policy-makers and actors involved in implementation and consultancy. Learn more ...

© 2024 | Built by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy | All rights reserved. | Imprint | Privacy Policy